I am not Charlie. I am a Syrian living in Beirut, as many other Syrians do, most of whom are refugees fleeing death and destruction. Many of them died a few days ago, under the same sky that shades the Americans, French, Russians, Iranians, Palestinians, Iraqis and the Somalis. The blood froze in their veins, and their tiny lungs ceased inhaling the cold air. They lived in tents torn by the wind, covered with snow and swept away by torrents, on the same Earth where the world leaders who marched in Paris the other day live.

I am not Charlie, because I do not have the same rights, such as freedom of speech and breaking taboos. I rebelled four years ago, so I was killed by an army that holds my own nationality and shares my land, air and water – because the same leaders who marched in Paris a few days ago kept their mouths shut, watching me starving to death, being tortured, and suffocating from chemical weapons. They were in their palaces, silently watching TV, reading about my tragedy and doing nothing about it. They have expressed their concerns and sorrow, they might have even shed a tear or two, but never once have they gathered like they did in Paris.

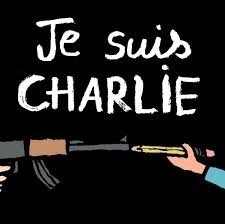

I am not Charlie, but I stand against terrorism wherever it exists. I am a Syrian who replaced his Facebook profile picture with a picture of Charlie. A few days ago, I replaced that with a photo of Raef Badawi, a Saudi activist who was sentenced to 1,000 lashes and 10 years in jail on the charge of “insulting Islam.” Before that, I had replaced it with a photo of Santa Claus being arrested in Oman for proselytizing. I have replaced it with photos of Iranian activists who were arbitrarily sentenced to be executed. I have also replaced it with a photo of Qatari poet Muhammed Bin Aldeeb al-Ajamee, and with a photo of the victims of Peshawar school in Pakistan. Yes, I am a Syrian who always finds the time to read about violence and human rights abuse around the world. Very few people have the time to sympathize with my case. Every morning I wake up to find myself on the unwelcome list in a new country. Every morning I wake up to find myself ejected from my job, my home, or even my tent. Every morning I lose another part of my soul, yet I am still able to sympathize with others. This is because I believe in freedom and dignity wherever they are needed, and wherever they are violated.

I am not Charlie because I refuse to use the word ‘but.’ I do not say, “I am against killing civilians, but…” or, “I am against tyrants, but I like their secularism.” I do not say, “I support people’s freedom in Afghanistan, Bahrain, Saudi Arabia and Palestine, but not in Syria.” And I do not say that I am against foreign interference, with the exception of the Iranians, Russians, or Americans. I also find it hard to condemn those who call for the American interference against the criminal regime, then I welcome the calls for the coalition intervention against ISIS.

How could I be Charlie, when world leaders call themselves Charlie? How could I be them? I wonder again about the psychological structure of the public opinion. ISIS is indeed terroristic, and attacking and killing 12 journalists and cartoonists in cold blood are acts of terrorism. But – and this ‘but’ is sacred – why is the Syrian regime not considered terroristic? How could killing 12 people be worse than killing over 200,000 Syrians in less than four years? What was the effect of the 50,000 photos, leaked by CNN and the Guardian, of detainees who had been tortured and killed inside Syrian prisons? Is this kind of torture not considered terrorism? Or does the identity of those tortured define if this was terrorism or just another worrying case of human rights abuses? If the regime had used these kinds of torture against foreign reporters, would the West have had the same reaction?

I will be Charlie when you allow me to be. When you admit that I am a Charlie, or a victim of a terrorist regime that bombs me, destroys my home, tortures me, and tears me apart like a piece of cloth, which proves what kind of Syria the regime wants. I would be Charlie if you gave me the right to live in dignity and the right to express myself freely without having to face terrorist guns, air strikes, or enforced starvation. I would be Charlie if you gave me the right to have my body found and buried properly in a grave that my parents could visit when things become difficult for them – as they often do.

Translated and edited by The Syrian Observer