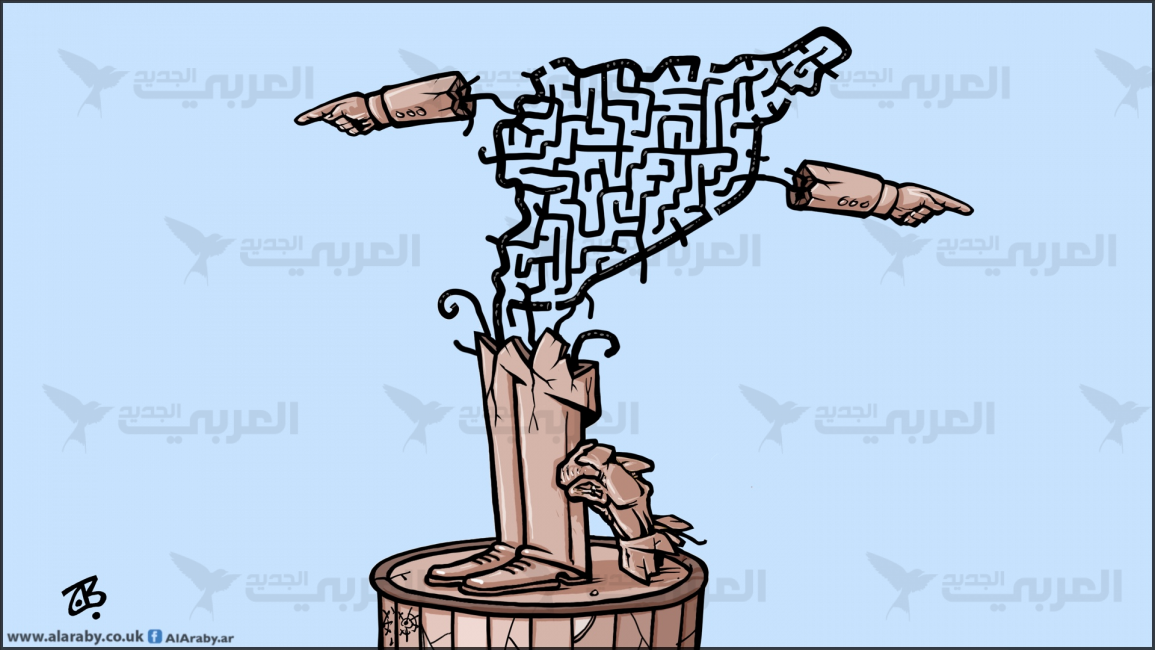

Syrians remain absent from the political process in their own country. Despite the fall of the Assad regime, the transitional authorities have continued to exclude popular participation, relying instead on top-down appointments across institutions that should, in principle, embody democratic values—local councils, unions, and professional syndicates. These bodies, which could feasibly conduct elections in many areas, remain unelected and under government control.

The same dynamic applies to Syria’s legislative body, referred to in the constitutional declaration as the “People’s Council”—an institution intended to represent the Syrian public during the transitional phase. Yet in reality, the obstacles to holding legislative elections remain formidable. There is still no political party law to organize public life, the civil registry is in disarray, and the issue of internal displacement and diaspora voters remains unresolved. Syria lacks an electoral law that could govern even a minimal parliamentary process.

In the absence of elections, the regime has opted to fill the legislative vacuum by appointing members to the People’s Assembly. A presidential decree established a High Committee tasked with selecting council members. Two-thirds are chosen through indirect voting by locally selected “sub-electoral bodies,” while the remaining third are appointed directly by the president—under the pretext of ensuring competence and fair representation.

Elite Appointments, Not Representation

In Damascus, members of the sub-electoral bodies were selected in each neighborhood based on approximate population size, in cooperation with pre-appointed local councils and with the governorate’s final approval. Selection criteria included good reputation, revolutionary credentials, community standing, and preferably a university degree. These bodies were then tasked with nominating council members from among local elites and intellectuals.

The process, however, falls far short of genuine political representation. Selecting community notables to elect legislators on behalf of the people is fundamentally undemocratic. While appointing technocrats and respected figures may be justified in local administration, parliamentary politics requires public platforms, party competition, and programmatic debates—none of which exist in the current climate.

When the selected bodies from Damascus gathered at the Opera House, open discussion was suppressed. Attendees were instructed to submit questions through a mobile application, which allowed moderators to filter or alter submissions before presenting them—if they were presented at all.

Notably, the term “democracy” is absent from both the constitutional declaration and official rhetoric. Even if formal democracy is currently infeasible, its spirit—open political dialogue—should guide the transitional period. Without it, the People’s Council becomes a rubber stamp for the ruling authority’s agenda.

A Power Grab in Disguise

The current authorities do not seek genuine popular engagement. Rather, they view themselves as a ruling group aiming to consolidate control over every aspect of political, social, and economic life. They perceive Syrian society through a pre-national lens—divided into religious, tribal, regional, and ethnic communities—and prefer to organize politics around these identities. These traditional groupings are easier to control and co-opt, especially when stripped of political awareness or access to open dialogue.

What Syria needed instead was a national political convention, inclusive of party representatives and independents, with legislative powers during the transition. This body should have operated transparently, under media scrutiny and public oversight, with a clear mandate to draft a new constitution, enact party and electoral laws, and oversee future elections. Such a process could have laid the groundwork for rebuilding political life around policy platforms and open debate, not elite consensus.

But democratic transition was never the goal. According to the constitutional declaration, the executive—represented by the president and cabinet—remains beyond accountability. The elected two-thirds of the People’s Council must be independents; party blocs are excluded. Meanwhile, the president will likely appoint figures affiliated with—or part of—the Hay’at Tahrir al-Sham (HTS) movement, especially those working under the General Secretariat for Political Affairs, which increasingly functions as a de facto ruling party, replacing the Baath.

A Fragmented and Stalled Transition

The absence of a democratic roadmap has left Syrian society disoriented. Traditional opposition parties, which were structured to resist the Assad regime, must now revisit their outdated methods. Their slogans for democratic alternatives lack operational mechanisms. Meanwhile, the arrival of HTS—a former armed faction now positioning itself as a political force—adds a further layer of complexity to Syria’s post-Assad landscape.

Syria remains divided geographically and politically. The transitional authority’s actions suggest that the country has not yet entered a true transitional phase. Rather, it is laying the groundwork for future conflict by establishing a sectarian, militarized regime with Islamic overtones—one that risks igniting further strife, whether along sectarian lines or over internal power struggles and spoils of the state.

To move forward, Syrians need clarity about the nature of the current phase and a renewed focus on reclaiming the political space. Otherwise, they risk having that space permanently reshaped to serve the narrow interests of a new ruling faction.

This article was translated and edited by The Syrian Observer. The Syrian Observer has not verified the content of this story. Responsibility for the information and views set out in this article lies entirely with the author.