Many Syrians greeted the introduction of the new currency with the same joy children feel when donning new clothes on the morning of Eid. Yet changing a currency is not an act of pageantry or a gesture for amusement. It is a sovereign decision of profound consequence and sensitivity—one that affects people’s finances, price perception, savings, and everyday transactions.

Success is not measured by the elegance of the design or the symbolism of the emblem, but by the presence of a coherent stabilization plan that either precedes or accompanies the decision. It must be underpinned by a clear legal framework, competent executive capacity, and a robust communication campaign that avoids confusion and precludes fraud. Absent these components, “reform” risks becoming a mere change of names and numbers, leaving inflation and structural imbalances untouched.

Such a step is not the domain of transitional governments; it is the prerogative of elected ones. It must follow political, economic, and societal debate, be passed through legislation by an elected parliament, and receive presidential assent.

In this context, it is worth examining the experiences of France in 1960 and Turkey in 2005.

- France 1960: Renaming the Currency as the Culmination of a Stabilization Package in the Early Fifth Republic

France introduced the nouveau franc on January 1, 1960, following years of post-war inflation, financial imbalance, and political turmoil exacerbated by the Algerian War. The measure itself was simple in form yet momentous in impact: one new franc equaled one hundred old francs.

This initiative formed part of the Pinay–Rueff Plan, adopted in late 1958—a package combining monetary reform with fiscal discipline and a devaluation aimed at restoring external credibility and reinforcing stabilization.

Crucially, the reform was anchored by strong political leadership. President Charles de Gaulle treated economic stabilization as essential to consolidating the nascent Fifth Republic. Finance Minister Antoine Pinay led the reform process to such an extent that the new currency was popularly dubbed “Pinay’s franc.”

Yet what mattered most was not merely what France decided, but how it decided it. De Gaulle’s backing ensured political coherence, precluding government disputes or partisan interference. The reform was thus presented as a national project, not a technocratic maneuver.

It was supported by meticulous technical preparation, led by an expert committee under Jacques Rueff. The transitional nature of the early Fifth Republic allowed the executive to act swiftly and decisively. The renaming of the currency followed broader stabilization measures, giving it the appearance of a natural conclusion to a wider economic strategy.

The reform was codified in the 1960 Finance Law (December 26, 1959), which strengthened its credibility by linking the currency change to the annual fiscal framework—diminishing the sense of it being a transient political gesture.

On the effective date, values across the economy—from prices and wages to bank accounts and contracts—were recalculated by dividing by one hundred. Transitional arrangements mitigated confusion: dual pricing was introduced, new notes were issued gradually (some with updated printing), and certain old coins circulated temporarily as “centimes.” The principle was clear: a sharp numerical cut, followed by a carefully managed adjustment phase.

- Turkey 2005: Renaming the Currency as the Outcome of Post-Crisis Disinflation

Turkey’s reform came in a markedly different context. The aim was to end the impracticality of a currency burdened by excessive zeros after decades of high inflation. Thus, the Yeni Türk Lirası (YTL) was introduced, with one new lira equaling one million old liras—a six-zero cut.

Crucially, Ankara did not implement this change amid rampant inflation. The renaming followed successful post-2001 crisis stabilization programs that had already curbed inflation, allowing the reform to be presented as a result—not a substitute—of stabilization.

Then Prime Minister Recep Tayyip Erdoğan played a pivotal role in giving the reform both political and symbolic momentum, portraying the old currency as a relic of decline and the new as a sign of renewal. This narrative was instrumental in aligning public, market, and administrative behavior, ensuring cohesive implementation.

The process was underpinned by Law No. 5083, which provided a clear legislative framework well in advance. This early legal clarity enabled nearly a year of preparation—updating accounting systems, adjusting pricing mechanisms, modifying contracts and wages, and readying the logistics for new currency issuance.

The Central Bank of Turkey managed technical and executive tasks—designing and distributing the new currency, and overseeing the phased withdrawal of the old—while the government handled legislation and public communications.

Throughout 2005, both currencies remained legal tender, supported by mandated dual pricing displays. This eased the transition for consumers and businesses alike, softening the psychological and operational impact. Later, once the public had adapted, the “new” designation was dropped, and the currency resumed its original name: the Turkish lira.

Common Elements in Both Experiences

- Political decision at the highest level: Centralized authority ensured consistency of message and decision, eliminating institutional ambiguity and curbing rumors or speculation during a sensitive transition.

- Clear and detailed legal framework: Laws precisely defined conversion rates and dates, detailing how wages, savings, contracts, taxes, rounding, oversight, and penalties would be managed.

- Disciplined institutional execution: With clearly delineated roles for the Ministry of Finance, central bank, commercial banks, and regulators, supported by operational readiness—such as updated systems, ATM calibration, payroll adjustments, and logistics for currency issuance.

- Transitional arrangements to ease daily friction: Measures included dual pricing, parallel currency circulation for defined periods, and standardized practices for merchants to maintain market stability and prevent exploitation.

- Comprehensive public awareness campaigns: Conversion rules were explained in accessible language, with targeted training for retail, banking, and accounting sectors. Media campaigns and support channels were established to minimize confusion and curb price manipulation under the guise of “conversion.”

- Integration with broader stabilization efforts: Renaming the currency was tied to fiscal and monetary reforms, ensuring the move addressed root causes of inflation and imbalance rather than simply changing the symbols of the problem.

What about Syria

In Syria, by contrast, the move has the hallmarks of haste. It has come without the level of national consultation that a decision of this magnitude requires, and it has been advanced by an interim authority operating without the political and institutional safeguards that underpinned the French and Turkish experiences.

Most critically, it has not been anchored in legislation debated and passed by an elected parliament, nor embedded within a stabilization package capable of giving the new unit lasting credibility. In these conditions, the change risks being received not as the culmination of economic recovery, but as an administrative shortcut – a rebranding exercise that shifts symbols and denominations while leaving the underlying drivers of inflation, distrust, and structural imbalance intact.

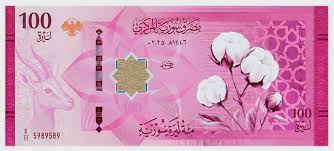

Even worse, Syria’s introduction of a new currency series is flawed due to the exclusion of smaller denominations below 10 Liras. This design choice is likely to cause denomination-induced inflation, where the absence of smaller units forces prices to be rounded up. This disproportionately affects low-income households, inflating the cost of basic goods and eroding purchasing power. Although presented as a step towards simplification, the reform risks exacerbating inequality and distorting everyday transactions. Without smaller denominations, the new currency may function as a regressive tax on the poor, undermining its own goals of economic stability.