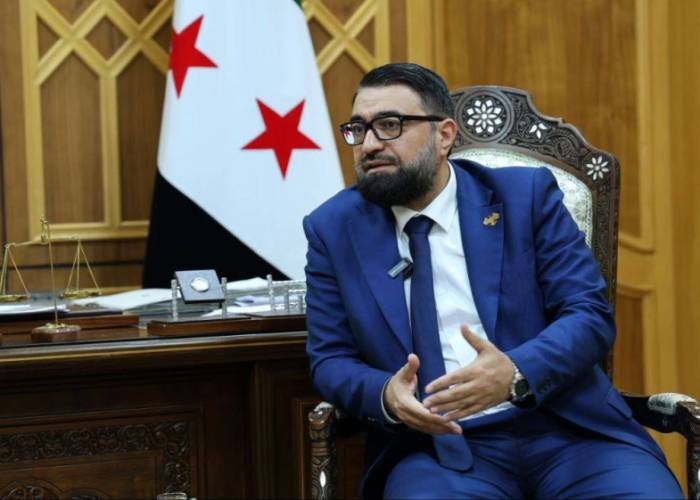

Dr Mazhar Al-Wais, Syria’s Minister of Justice, has published an article titled “Has the Transitional Justice Process Been Delayed?” purporting to address public anxiety. Yet the piece ultimately generates more doubts than it resolves. Beneath the veneer of revolutionary language and institutional pledges sits a harder, unavoidable question: are we moving towards genuine justice, or merely constructing a legal façade designed to defer long-overdue reckonings?

First: The “Gradualism” Trap and the Politics of Over-Institutionalisation

The minister repeatedly invokes a “gradual path” to justify the absence of tangible results. The danger is that transitional justice—an urgent national imperative—becomes a bureaucratic routine. While victims await decisive, immediate measures, the minister speaks instead of “structures”, “training workshops”, and “complex approaches”. The subtext is clear: the state can always bury the file in technical committees, stretching time until political courage is no longer demanded.

Second: Judicial Independence, or Merely a Rebrand?

The article speaks of “reintegrating dissenting judges” while “excluding those implicated” in abuses, but offers no transparent criteria. Who determines what constitutes “judicial integrity”? Will the screening process become a tool for political settling of accounts—or, conversely, a back door through which judges are restored because they did not personally shed blood, even as they spent years laundering authoritarianism with legal language?

Absent independent oversight—particularly from civil society and victims’ representatives—the promise of “judicial independence” risks remaining a slogan managed by the same ministry claiming to deliver it.

Third: The “International Support” Excuse and the Question of Reparations

It is deeply troubling that the minister links core obligations—reparations, truth-seeking, and redress—to “international support” and “lifting sanctions”. This framing amounts to an implicit abdication of the state’s duty towards its own citizens. Reparations are not a charitable project contingent on donors, nor a prize to be unlocked by geopolitical bargaining. They are a sovereign, legal obligation.

When victims’ rights are tethered to international negotiations, those rights become hostages to diplomatic manoeuvre and political trade-offs.

Fourth: The Rhetoric of “Incitement” and the Silencing of Scrutiny

Most alarming is the minister’s call for intellectuals and public figures to refrain from “pressuring” or “rushing” the process, warning that such demands may constitute “unintentional incitement”. This rhetoric echoes authoritarian paternalism: public scrutiny is recast as disruption; insistence on justice is treated as recklessness.

Transitional justice does not survive without pressure—from victims, families, lawyers, journalists, and civil society. Attempts to “calm” that pressure are, in practice, attempts to drain justice of its substance and convert it into administrative theatre.

Fifth: Dangerous Vagueness on the Missing

Although the minister refers to a “National Commission for the Missing”, he provides no timeline, no commitment to immediately open mass graves, and no pledge to declassify prison records. Vague phrases such as “preserving evidence” and “coordination” do not meet the needs of families who have waited more than a decade for answers.

The “corridor of justice” promised for 2026 could easily become a legal labyrinth—unless it is backed by unmistakable political will that prioritises truth over a fragile, cosmetic stability.

A Message from the Families of the Missing

Minister Al-Wais writes as a statesman managing a crisis—not as an official ending it. Syrians do not need conceptual corrections; they need a corrected reality. Justice that is not felt in homes, property records, workplaces, and in the freedom of detainees remains paper justice: filed in the archives of the Ministry of Justice, and nowhere else.

If “gradualism” becomes a doctrine for delay, then the state is not building transitional justice—it is managing the public’s expectations of it. And that, in a country built on the wounds of the disappeared and the dispossessed, is not a path to stability. It is a recipe for its collapse.

This article was translated and edited by The Syrian Observer. The Syrian Observer has not verified the content of this story. Responsibility for the information and views set out in this article lies entirely with the author.