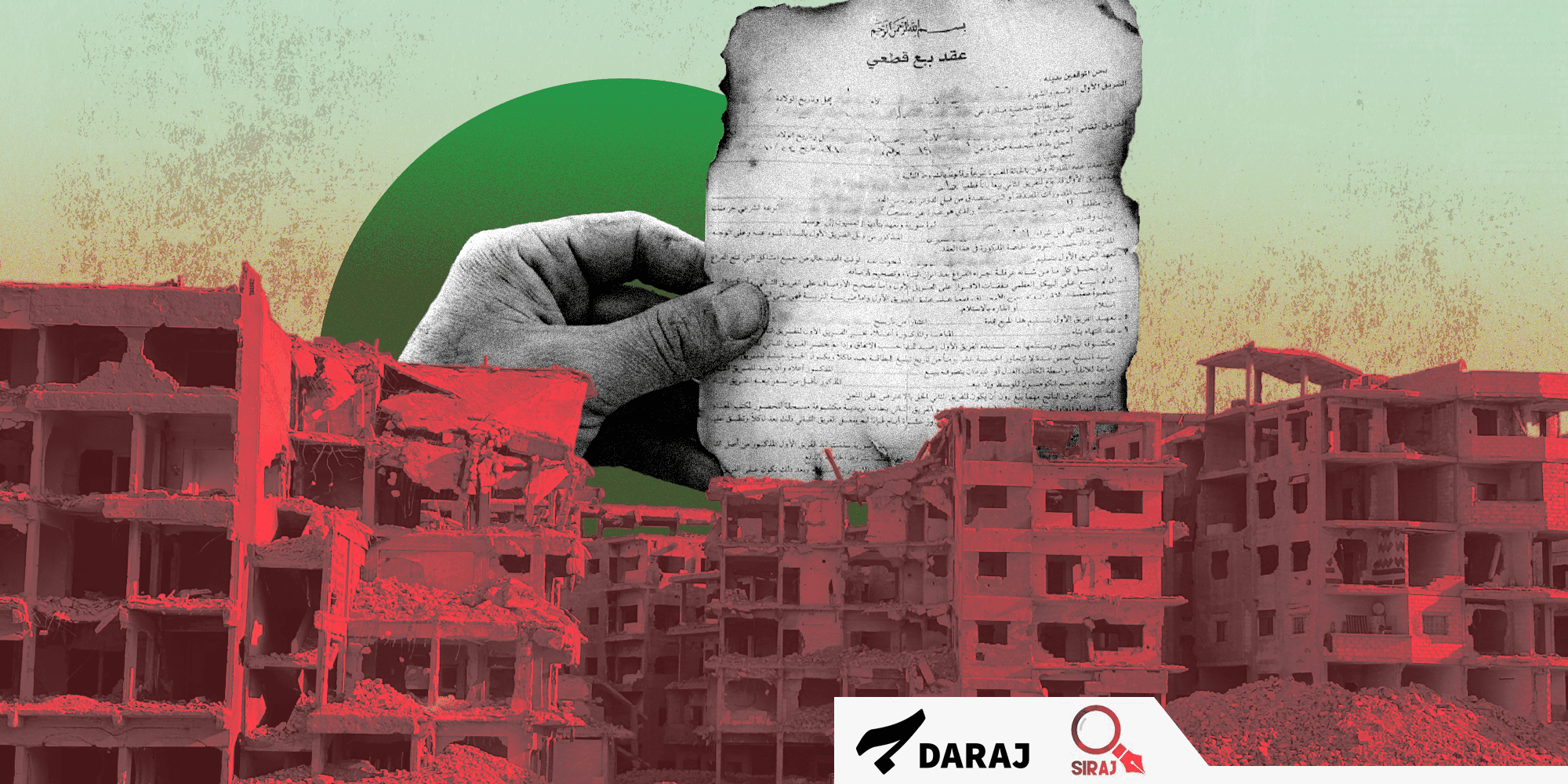

As Syrians begin returning home after the ouster of the Assad regime in late 2024, many are confronting an unexpected and deeply destabilizing reality: proving they own the homes they left behind has become a near-impossible task. What should be a moment of return and recovery has instead turned into a protracted legal and bureaucratic ordeal shaped by years of war, systematic looting, and a fractured legal order.

The Core of the Crisis: Lost Papers, Occupied Homes

The problem begins with the simplest of facts: countless returnees no longer possess the documents that once proved their ownership. The essential “Green Taboo” deeds were burned, stolen, or lost during the conflict. In cities such as Darayya, entire property registries were obliterated.

This vacuum created fertile ground for exploitation. Many returnees now find their homes occupied by strangers or discover that their properties were sold and resold multiple times using forged documents. With no surviving paper trail, they have little legal standing to reclaim what is rightfully theirs.

A Legal System Stacked Against Them

Seeking legal remedy is a daunting undertaking. Syria’s property laws form a maze of more than 200 overlapping and often contradictory statutes. Although the new Ministry of Justice has begun efforts to reconstruct lost records, its requirements remain impractical: returnees must present certified copies of the very documents they lost.

The legacy of the former regime further complicates matters. Laws such as the 2012 Anti-Terrorism Law were used to freeze and confiscate the properties of displaced persons and political opponents under sweeping, arbitrary accusations. Urban-planning legislation, most notably Law No. 10 of 2018, enabled dispossession by designating redevelopment zones where ownership had to be re-established within narrow deadlines—deadlines impossible for exiles to meet.

Twofold Anguish: Formal and Informal Areas

The crisis manifests differently across the country.

In formally planned areas, returnees face labyrinthine regulations and sluggish compensation mechanisms.

In informal settlements—where a large share of Syrians lived—the situation is even more precarious. Properties there were often exchanged through unregistered customary contracts. With no official record to begin with, residents have no legal basis to assert ownership, leaving them acutely vulnerable to fraud, eviction, and renewed displacement.

The scale of the challenge is immense. UN estimates indicate that of Syria’s pre-war 5.5 million homes, hundreds of thousands were destroyed, leaving roughly 5.7 million people in need of housing assistance. A 2025 UN Commission of Inquiry report documented “systematic looting and pillage” of civilian property—often by military factions such as the Fourth Division—describing it as a major obstacle to safe and dignified return.

Seeking Solutions Beyond the Status Quo

Government measures, including the creation of specialized property courts, are viewed as necessary but insufficient. Legal advocates and civil-society groups argue that the scale of dispossession demands a more ambitious transitional-justice approach.

Proposed solutions include:

- issuing provisional property titles

- accepting community-sourced testimony and alternative forms of evidence

- overhauling the restrictive legal framework inherited from the war era

Such reforms, they argue, are essential for restoring trust and enabling genuine restitution.

For now, the dream of return remains incomplete for thousands. They may have crossed back into their homeland, yet without the document that proves their home is theirs, they remain suspended in a state of legal and existential uncertainty. Their futures are held hostage by a labyrinth of destroyed archives, contradictory laws, and the lingering shadows of a decade of conflict.

This article was translated and edited by The Syrian Observer. The Syrian Observer has not verified the content of this story. Responsibility for the information and views set out in this article lies entirely with the author.