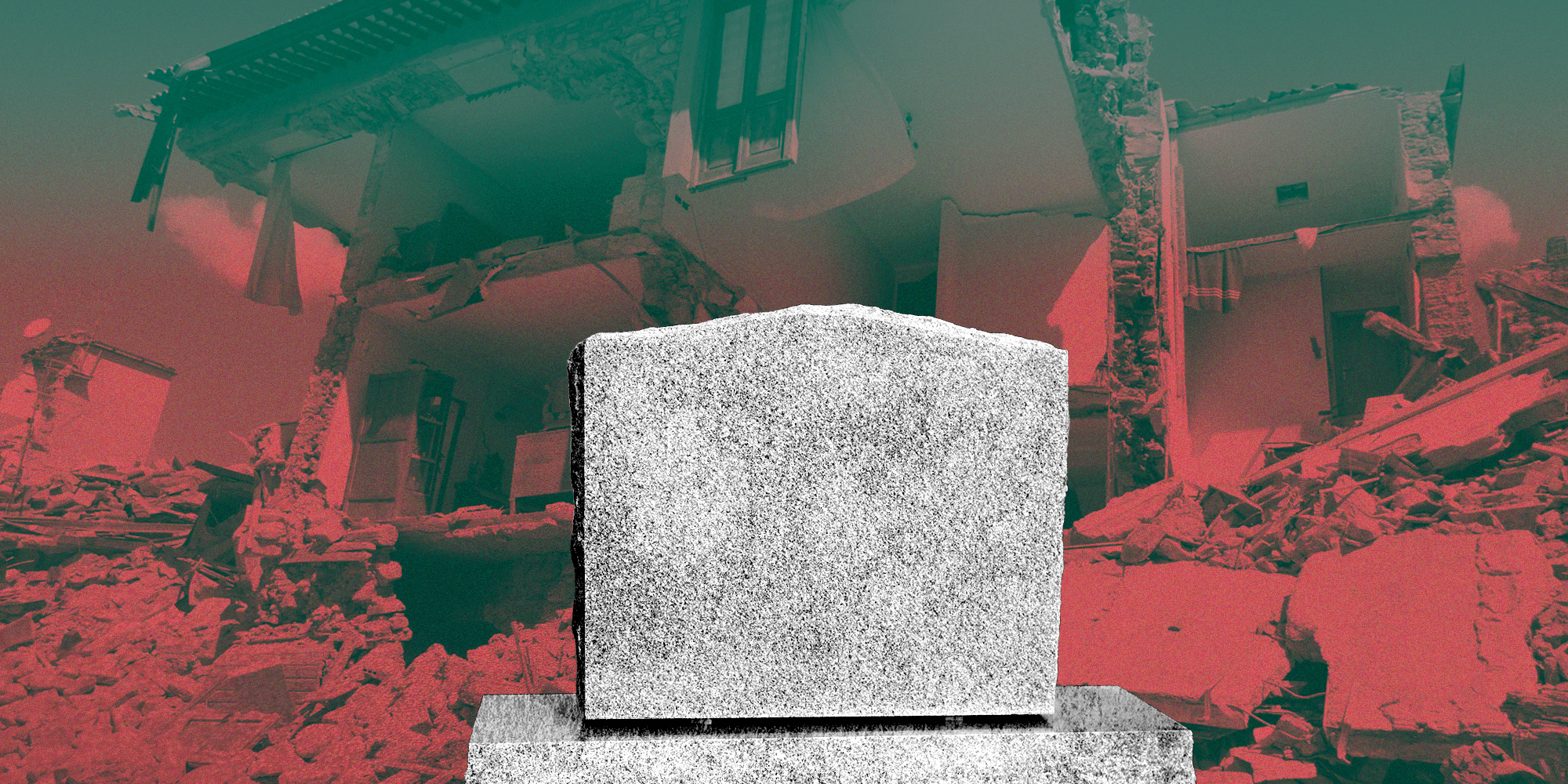

Three years after the devastating earthquake of February 6, 2023, the grave of seven-year-old Islam al-Rifai stands as a quiet rebuke. Her headstone carries two identical dates—born February 6, 2016, died February 6, 2023—an unbearable symmetry that distills a tragedy shaped by both natural disaster and human design. Her family’s story reveals how the violence of displacement collided with the failures of policy, producing a catastrophe within a catastrophe.

On the night before the quake, the al-Rifai family’s apartment in Hatay offered a fragile refuge. They had gathered to celebrate Islam’s seventh birthday, a brief moment of joy carved from years of upheaval. At 4:17 a.m., the celebration vanished. The roof collapsed, killing Islam, her father Sharif, her sister Bisan, and her brother Saif. They became serial numbers in a foreign cemetery; Islam’s grave is marked simply as #71.

Engineering Ready-Made Death

Their deaths were not the work of shifting tectonic plates alone. They were the predictable outcome of a system that cornered Syrian refugees into the most vulnerable spaces. Turkey’s “address-based registration” rules confined refugees to specific districts, often older and cheaper, where buildings had long exceeded their safe lifespan. The “residential address” became more than a bureaucratic requirement; it became a constraint enforced by the threat of deportation.

This form of spatial restriction pushed refugees into structures that could not withstand even moderate tremors. As one Syrian in Hatay described it, it was “enforced residence” within a framework of population control.

The earthquake exposed a bitter truth: modernity was often an illusion. A Deutsche Welle report, citing Turkish Statistical Institute data, found that 51 percent of those affected were in buildings constructed after 2001—supposedly under stricter safety codes introduced after the 1999 İzmit disaster.

Professor Haluk Sucuoğlu, an earthquake engineering specialist at Middle East Technical University in Ankara, explained the failure succinctly: “The problem was the lack of implementation.” He described a system hollowed out by corruption, where contractors leveraged political ties to evade oversight and where inspections became a paid formality riddled with conflicts of interest.

A System of Collusion

The collapse of the upscale “Renaissance” complex in Hatay, which killed hundreds, exposed the gulf between glossy marketing and structural reality. The disaster was not an accident of engineering but the product of a network of negligence, permissiveness, and political protection.

In the aftermath, Turkish prosecutors charged 134 contractors in connection with building failures, arresting some as they attempted to flee the country. The al-Rifai family did not die in an aging structure; they died in a system that normalized shortcuts, rewarded connections, and allowed “construction amnesty” laws to override basic safety.

When Survival Becomes a Privilege

In the critical hours after the quake, survival itself became stratified. Testimonies and documented accounts revealed a hierarchy of rescue. Priority was sometimes given to buildings housing foreign staff or international institutions, while response teams arrived late—or not at all—in neighborhoods densely populated by refugees. Families dug with their hands, waiting for machinery that came too late.

Syrian journalists on the ground, including Elaf Yassin—who lost her brother and sister-in-law—recorded this lethal neglect, describing exhausted crews and inadequate equipment arriving long after the window for rescue had closed.

In a painful twist, Syrians who rushed to save neighbors were often met with suspicion. Young men who pulled survivors from the rubble were accused of looting, their courage overshadowed by the stigma attached to their refugee status. The earthquake revealed a brutal hierarchy of humanity.

Geography of Loss

The map of devastation stretched from Hatay to Marash, Islahiye, and Antep, where Syrian residential clusters collapsed in seconds. While official Turkish figures recorded around 6,100 Syrian deaths, rights groups believe the toll is far higher, with entire families buried without documentation.

The tragedy reached its logistical peak at the Bab al-Hawa border crossing, which became a corridor of the dead. More than 1,800 Syrian bodies were transported from Turkish morgues and streets to be buried in northern Syria—a final, involuntary return.

The Roof That Fell Twice

Standing before Islam al-Rifai’s grave requires naming the truth plainly. The roof that collapsed in Hatay was not the first to fall on her family. The first collapse happened in Damascus, when homes became battlegrounds and millions were forced into exile in search of safety that proved illusory.

Islam and her family were not only victims of an earthquake. They were casualties of a long erosion of safety—a process that began with the loss of home and citizenship and ended beneath the rubble of displacement. The quake did not create a new tragedy; it extended an old one.

Responsibility does not end at the borders of the state that produced the displacement. For years, the international community has treated Syrians as a chronic emergency to be managed rather than resolved—a statistic in reports, a budget line vulnerable to cuts. Even after the earthquake, thousands remained in precarious legal situations, dependent on temporary protection regimes that offered neither permanence nor full security.

Justice for Islam

The al-Rifai family’s story cannot be contained within the phrase “natural disaster.” It is the culmination of a system that legitimized displacement, normalized precarity, and turned survival into a privilege.

Justice for Islam requires more than mourning her name. It demands a redefinition of protection itself: that the right to life must never depend on chance, and that no roof—anywhere—should remain a deferred, calculated risk of death.

This article was translated and edited by The Syrian Observer. The Syrian Observer has not verified the content of this story. Responsibility for the information and views set out in this article lies entirely with the author.