My name is Abu az-Zein.I was born in the countryside of Latakia. I am 43 years old.

I will tell you how I feel during these difficult days.

My main job is as a driver in the Emergencies Department at the General Electric Company. I earn a monthly salary of 15,000 Syrian Pounds, which is not enough to keep me, my wife and five children for more than 15 days.

Before 2011, I borrowed from the bank and bought three cows to provide me with additional income in order to cover the expenses for the rest of the month, although I was unable to save anything extra to help in difficult times.

When the events broke out in Syria, and I didn’t stand with any party. My main concern was how the dilemma of living, when prices rose to three times the previous amount and the value of Syrian Pound decreased.

I did not think of participating in the state's military actions, because I was sure that if I died, my children would become homeless. My position was clear.

At some stage, some people associated with the National Defense Forces came to our village. They offered us light weapons – rifles, and Kalashnikovs. I told them clearly that I was willing to carry arms but only to defend my village, but that I was not ready to be assigned any task outside the boundaries of the village. I told them I did not want any salary from them.

About a year after the outbreak of the crisis, I sold the three cows because we were no longer able to secure food for them. As for my job in the Emergencies Department, I managed to hold on to it, despite frequent threats.

I remember feeling I could die at any moment. In the area of Rabia, one of the villages that we had to check frequently for maintenance, there were battles between the insurgents and the state, and as a result of the shelling, the electrical grid in the area was damaged and the power cut off.

The mayor of the village, who was a Turkman, called us and begged us to repair the grid. We knew this man from before and we had a choice – no one could oblige us to go under these circumstances. The workshop consists of five employees, three Alawites and two Turkmen. We are like brothers because we spend more time together than we do with our families. Everybody looked to me as the driver and the decision-maker.

The memories about that poor village passed through my head; I remembered how much having electricity meant to them, because it is connected directly to the water, and there is no drinking water without the electric pumps. I remembered my sons when they are thirsty, and I made the decision to go.

I called the mayor and told him that there were gunmen. His response was encouraging: "Abu az-Zein, you are aware of your status among us, do not worry because you are an Alawite".

We went to repair the grid. We were terrified moving between the falling shells, but we managed to come back unharmed.

Now, however, if the same problem occurs, I will not go. The mayor I knew is no longer the decision-maker there, and there are a lot of frightening strangers there.

The economic problems have continued, and I have had to sell some of the land I inherited from my father. Whenever I sell some of the land, I spend the night crying, but I never let my children see. My land is part of my soul, but it's not dearer than my children. I have very little left to sell and I do not dare to think of what next will happen after I sell it all; how would we live?

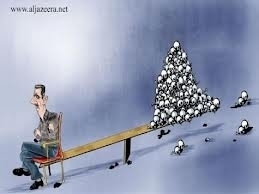

I voted in the presidential election, not because I am convinced of the concept of democracy, but because I am desperate and I fear that I may lose my job if I don't vote. I believe that the extremist Islamic movements that have proliferated in Syria want to kill us because we are Alawites, and I made a decision that if the moment of reality comes, and those extremists control our area, I will kill my children myself because I cannot leave them to suffer at the hands of these criminals.

With every day that passes, I tell myself: 'We are still alive, and that's good', but I do not dare think about the future because I'm afraid of it.

It hurts me so muchto think that in the past I used to go around and sleep in those Turkmen villages. I have only my memories of that now. I know that people there have become displaced and lost all their homes. I dream of going back to our normal life in the coming days, if we manage to stay alive.

......