There has been increasing talk recently in Western media about Assad’s victory over the Syrian revolution in the unequal fight he imposed on the unarmed protesters about eight years ago. The claim of victory rests on two main criteria: Assad’s survival in power and the expansion of the circle of control over Syrian territory. There, the story ends, and talk begins about the reconstruction and normalization process underway between the Assad regime and a number of countries in the region and the world.

This sort of diagnosis has a great deal of simplification, as well as implications for how we understand the current conflict in Syria. It’s true that the ratio of regime control on the ground has expanded because of Russian and Iranian support and that the area controlled by other players has declined. However, first of all, it is still a long way from controlling all Syria’s territory. Second, control over the ground is one thing, and the ability to keep it under control is another thing entirely. Over the last eight years, a large number of parties have traded control over a majority of Syria’s territory—it has gone from the regime to the opposition to the Islamic State (ISIS) and then back to the regime. But it is certain that the regime does not today possess that which will allow it to maintain its control over the largest portion of Syria, let alone all of Syria. Some may be betting that it will be able to do this, but I believe that this is still far-fetched. The regime’s control is weak, even over the areas which it now holds.

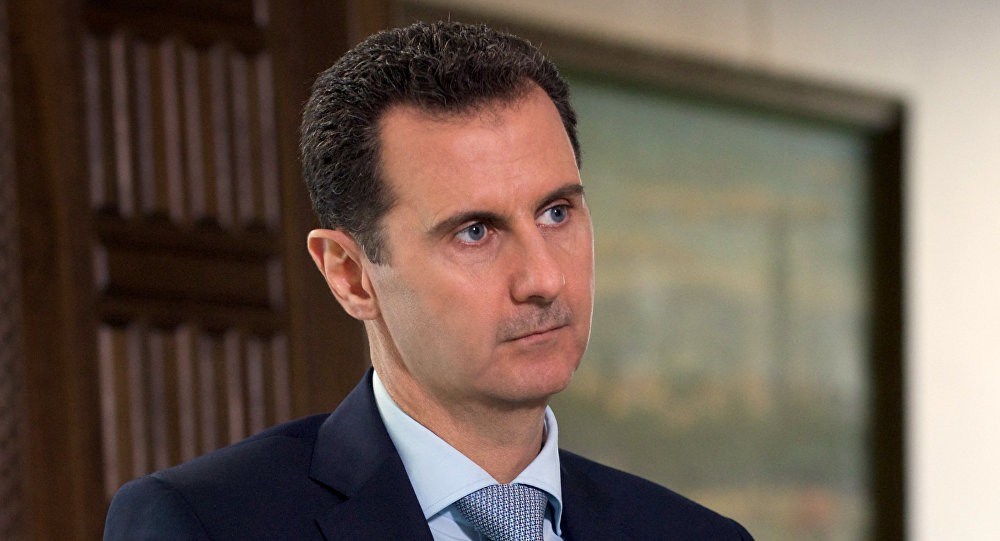

Last Sunday, the Bashar al-Assad regime erected new statues of Hafez al-Assad in Daraa city, where the Syrian revolution broke out in 2011. This act stirred anger in the streets, where residents had taken down the original statue about eight years ago. Despite the fact that the regime took control of this area just a few months ago, this did not prevent people from gathering, demonstrating and chanting slogans against the Assad regime to protest this act. These kinds of indications are very important, because they reflect the ability to continue the fight against the Assad regime by means different than those of recent years. This is the most important part of my analysis of whether Assad has been victorious or not. Control on the ground is a temporary and fluid indicator, but the continuing protests against the Assad regime’s policies is more meaningful and a indicative criteria for calculating the victory equation.

In addition to all that I’ve noted, there are an unending number of internal and external challenges that the Assad regime will have to overcome before it can claim that it is able to survive as well as govern. These challenges are not limited to the economic aspect or to the matters of reconstruction, international legitimacy, or the return of refugees. It definitely goes beyond these, and could become much more difficult for the regime as international and regional players compete in and over Syria. The truth is that because of the Assad regime’s exhaustion and its political, economic and military weakness, it could be more afraid of these challenges than of the opposition. While brandishing the ISIS card had served it as a kind of salvation in undermining the opposition, this sort of card will not be useful in confronting these challenges in the future. In summary, the claim that the regime has settled the battle is short-sighted and superficial. Its also unrealistic, as the battle for Syria will continue for a not insignificant time, and in various forms.

This article was translated and edited by The Syrian Observer. Responsibility for the information and views set out in this article lies entirely with the author.