By: Pierre Abisaab

There have been unconfirmed but troubling reports circulating in the media about Abdul-Aziz al-Khayir, the leftist leader and activist who continues to be detained by the Syrian authorities. Usually, to ascertain whether this is true or not, and in the process, expel one’s sense of doom, one contacts Youssef Abdelke.

To be sure, the Syrian dissident artist almost always has accurate information on Khayir’s fate. For months now, Abdelke has been stubbornly fighting for the release of Khayir, his comrade at the Communist Labor Party (CLP), and head of the external affairs division at the National Coordination Body for the Forces of Democratic Change in Syria (NCB).

This time, however, Youssef did not answer his phone. There are no signs of life at his famous atelier in Souk Sarouja, in the heart of Damascus’ old city, where he had settled after his permanent return from Paris. So where is Youssef now?

The same old scenario has once again repeated itself: At a checkpoint manned by members of one security agency – exactly as had happened with Khayir upon his return from China last September – Abdelke was arrested on Thursday evening, July 18, near Tartous, along with NCB member Adnan al-Dibs and CLP member Toufiq Imran.

A statement by the Gathering of Independent Syrian Visual Artists accused regime agencies of arresting the three leaders and called for their immediate release. The Syrian Center for Media and Freedom of Expression also issued a statement calling on the Syrian government to “put an end to the policy of forcible disappearance as a form of punishment against peaceful activists and defenders of human rights and the freedom of opinion and expression.”

On Abdelke’s Facebook page, full of expressions of solidarity, one finds a YouTube link to “Ghurfa Saghira” (A Small Room), an old song written by Samih Shuqeir for Abdelke nearly 25 years ago when Abdelke was also in prison. One lyric goes, “How many times did we stay up, laugh and sing, in that small cozy room, and how many times did we cry?”

Many may recall the huge crowd at Atassi Hall in the Asaad Pasha Khan that came to greet the returning Abdelke. It was the first exhibition of his works that he attended in Damascus, after 25 years in involuntary exile.

In 2005, Abdelke decided to return to his home country, which never left his mind since the day he left, in May 1981. Abdelke’s experiences came to life in his works, which include engravings, charcoal and canvas paintings, as well as cartoons and essays.

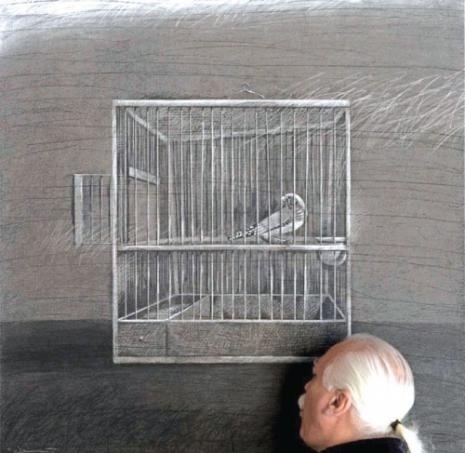

In Damascus, Abdelke’s tragedy would also leave its mark on his chefs d'oeuvres. Who among us was not taken aback by his works’ deafeningly silent character, with their manipulation of black and white and darkness and brightness? The objects of his art are totemic, as though they were the abrupt remnants of mysterious rituals, which Abdelke highlighted in a distinctive theatrical way: a severed arm with the fist still tight; decapitated fish; torn flowers and watermelons.

His works have an air of expressionist starkness, and symbolic abbreviation not shorn of surrealism. The knife, as in one of his works, is not really sunken into the table, but it is meant for our consciences.

After the crisis erupted in Syria, muted anger became the recurrent motif in his works. His recent paintings heavily feature themes of tragedy and bereavement presented in simplistic realism. In the words (Arabic) of colleague Emil Munim on Abdelke’s art, “We are now witnessing Abdelke in his post-disaster era, as the bereaved mother in the ‘Martyr’s Mother,’ ‘A Martyr From Daraa,’ and other works, bears witness.”

Following the outbreak of the Syrian uprising, Youssef decided to stay in the country, regardless of the fact that it was hijacked later, turning into a brutal civil war with many foreign liaisons. This is something that upsets Youssef and his honest comrades, who, unlike many of their peers, did not go on to collaborate with Western intelligence services and regional reactionary regimes.

Youssef and his comrades are only interested in the will of the people, and principles like unity, democracy, and other aspirations mentioned in the “statement of one hundred intellectuals” (Arabic) that Abdelke signed – and which possibly led to his arrest.

It does not matter if these legitimate and noble aspirations have no real forces fighting for them on the ground. It does not matter because it is dreams of utopia that drive great art and guide people. Utopia is the womb out of which freedom – or chaos – emerges.

For the artist, who spent his life dreaming of change, what else can he be expected to do today? Step back and wait for the next revolution? Or “advance toward the precipice,” in the words of our colleague Khalil Swaileh in a recent article (Arabic) about the Syrian artist in Al-Akhbar?

Abdelke knows that he is standing in the eye of the storm, but he cares neither for the contradictions nor the risks. Youssef is an unarmed artist facing a heavily armed and frenzied regime. So who, one wonders, is stronger? Who shall prevail in the long run?

Freedom for Youssef Abdelke and his comrades!

This article is an edited translation from the Arabic Edition.

......