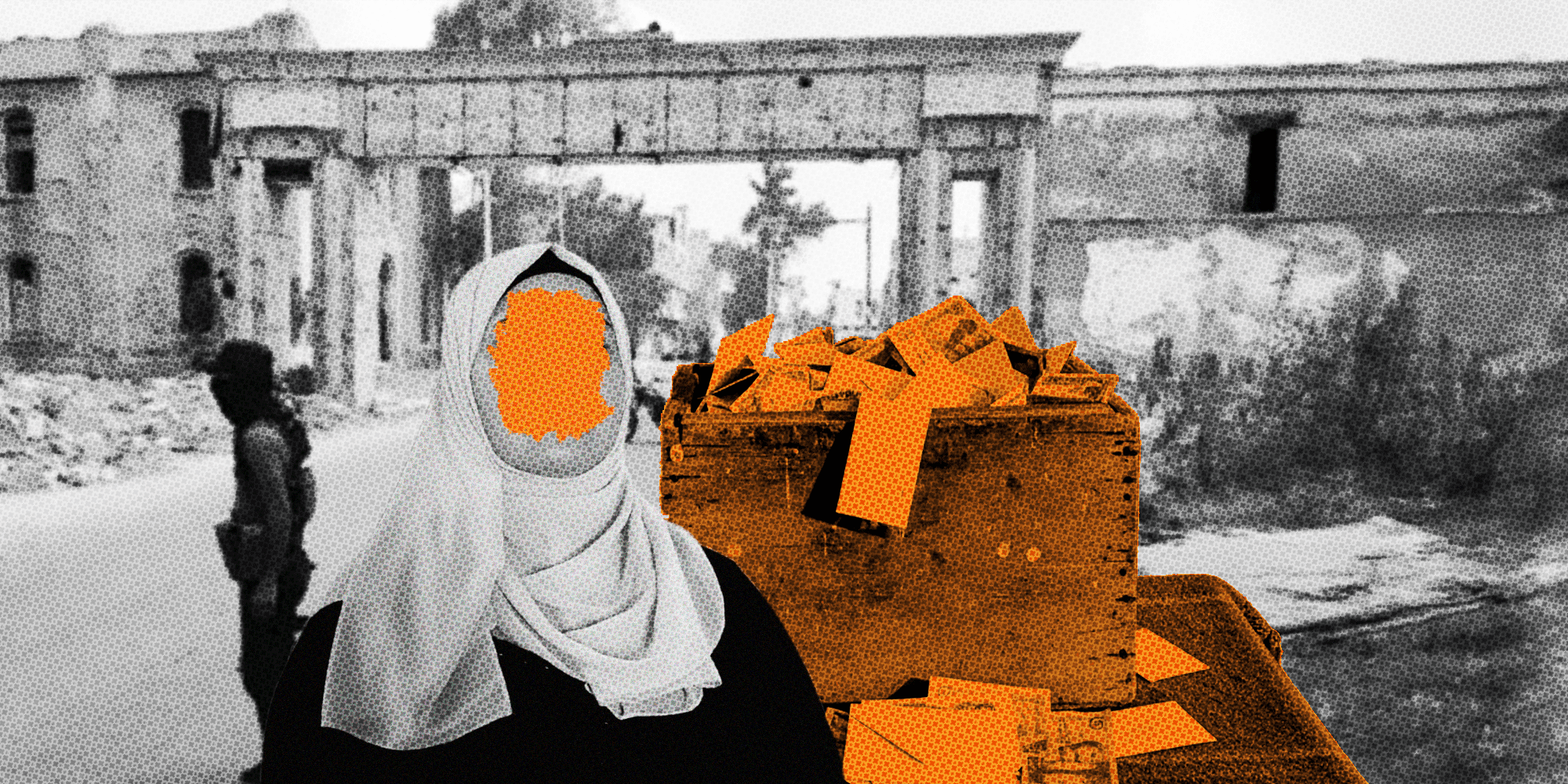

Kidnappings, rapes, and murders of women in Syria have become stories that flood social media, only to fade from public memory without clear accountability. Victims’ legal rights are being replaced by spectacles of sympathy, pity, and “donations.” The case of 23-year-old Rwan Al-Asad may stand as the starkest and most brazen example of this phenomenon.

Scenes of violence against women in Syria recur as if part of the daily news cycle. Abductions, rapes, and killings are broadcast on social media, then quickly vanish from public consciousness without visible reckoning – and sometimes with outright denial of the crimes’ occurrence. Each time, emotional outrage morphs into symbolic solidarity campaigns or donation drives, while perpetrators evade justice. This pattern is no longer a series of isolated incidents; it is woven into the fabric of daily life in areas under transitional authority, where victims’ legal rights are supplanted by performative displays of compassion and pity. The ordeal of Rwan Al-Asad is the clearest and most egregious illustration of this.

Rape in Broad Daylight – Then Donations

In September 2025, Rwan Al-Asad from the town of Salhab in rural Hama appeared in a video demanding the arrest of her rapists. Exhaustion and disorientation were etched on her face. She was forced to transform from a victim seeking safety into a witness to her own tragedy before millions of strangers.

In a subsequent video, she announced receiving around 25 million Syrian pounds from donors, sparking fierce debate over the transparency of the fundraising, the entity filming and posting the videos, and how her case shifted from a public rape into a social media “human-interest” story.

This campaign not only exposed Rwan’s name and location but redirected her ordeal into debates over donations and aid, diverting attention from demands for accountability. A Syrian activist posted a video naming the alleged rapists, their villages, and the faction under whose banner they operate, describing how these groups exercise total dominance over their areas, committing repeated violations without deterrence or repercussions – despite authorities’ awareness of the perpetrators’ identities or at least the evidence submitted by the victim.

The cycle repeats: organised crimes by known armed men generate initial shock on social media, followed by images, hashtags, and donation appeals. Days later, the victim appears in a flustered thank-you video and the episode concludes. Justice vanishes, replaced by a discourse of pity – as though the crime were an occasion for charity rather than an act demanding prosecution.

This pattern manifests clearly in the way cases rapidly pivot towards donation drives that expose intimate family details, turning victims’ tragedies into consumable content rather than catalysts for accountability.

When Tragedy Becomes Content

Rwan’s assault on 9 September 2025, as she returned from work to her village of Hurat Amurin, was swiftly transformed into viral content. Activists filmed her family’s home and publicised their private lives: a sick brother, unpainted walls, dilapidated furniture, a broken window. Rwan has been the sole breadwinner for her mother and brother since her father’s death in 2017.

One account, claiming to have the mother’s consent, launched “the largest donation campaign in Tartus,” urging people to transfer funds via local remittance companies while publicly listing his name and number. Another widely followed Instagram account entered the home, filmed every detail, and turned Rwan’s life into a series of videos to evoke sympathy and solicit donations – without once calling for the prosecution of her attackers or exerting pressure on authorities.

However genuine the organisers’ intentions, these campaigns reveal a painful paradox: is fixing a broken window sufficient while the criminals roam free? The family undoubtedly needs aid, but priority must go to arresting and prosecuting the perpetrators. Donations cannot prevent future crimes, and no humanitarian drive will restore Rwan’s sense of security while her assailants remain at large.

This spectacle strips the victim of her identity as a citizen with rights. She ceases to be a raped woman deserving redress and becomes a “humanitarian case” worthy of some cash and likes. She is reframed from a witness to systemic violence into an emotional narrative ripe for circulation.

A Recurring Pattern

Rwan’s case is part of a wider wave of abductions, sexual assaults, and violence against women across Syria’s coastal and rural areas in 2025. Investigative reports have revealed a surge in disappearances and kidnappings, particularly in Tartus, Latakia, and Hama, often involving ransom demands or repeated abductions. Examples include the daytime disappearance of Abeer Suleiman, whose family received an explicit ransom demand, and the kidnapping of 17-year-old Zainab Ghadir on her way to school, who returned under mysterious circumstances amid official silence.

Dozens of other cases have been logged under vague terms such as “temporary absence” or “mysterious circumstances,” vanishing from public discourse after a few days. The pattern is identical: initial shock online, waves of sympathy, donation campaigns, a thank-you video, then silence. There are no announcements of serious investigations or clear accountability. This sends a compounded message to victims and society alike: justice is absent, and criminals remain free.

This reality is no longer confined to social media narratives but documented in international reports, confirming that these incidents are not coincidences but part of a systematic pattern of violence and impunity.

A Reuters report on the surge in kidnappings found that many survivors refused to discuss their ordeals out of fear of reprisals or social stigma. Families reported that police did not take their complaints seriously, with investigations conducted superficially and incompletely. This enforced silence enveloping victims and their families echoes Rwan’s case, where she was compelled to go public demanding her rapists’ arrest because no one else stepped forward to hold them accountable.

Governmental Silence – Except When It’s ‘Trending’

The Syrian government has issued no formal response to the incidents highlighted by international agencies and human rights organisations. Local officials, such as Ahmad Muhammad Khair, head of media relations in Tartus province, have claimed that most disappearances stem from “family disputes or personal reasons” – without evidence – and even blamed victims themselves, suggesting they “run away to avoid forced marriage or attract family attention.”

This official rhetoric does not merely trivialise disappearances but reframes them socially to downplay their severity, leaving families in a justice vacuum. Authorities’ reluctance to probe seriously, veiled victim-blaming, and lack of political will to restrain armed factions leave violations unchecked.

Human rights data from the Syrian Network for Human Rights (SNHR) and the United Nations Population Fund (UNFPA) demonstrate that Rwan’s ordeal is not an isolated case but part of a larger reality. A June 2025 UNFPA report noted a rise in gender-based violence amid economic crises and displacement, with limited access to protection and psychological support. SNHR documented 1,562 killings across Syria in March 2025 alone, including 99 women – indicating that women are deeply enmeshed in the cycle of violence and devastation.

In Rwan’s case, the “trending” nature of her story finally prompted the Minister of Social Affairs and Labour to post a statement pledging to pursue the perpetrators and contact the family for reassurance. Khaled Murdaghani, director of internal security in the Ghab Plain region, said preliminary investigations revealed she had been abducted by two men on a motorcycle and taken to an agricultural field to be assaulted.

But the story did not end there. The suspects remain at large. Reports from the Syrian Observatory for Human Rights indicate armed men entered the village attempting to abduct Rwan as a hostage to pressure the captors of a Ministry of Defence element, amid threats of escalation.

This case is not a transient incident but a stark manifestation of recurring impunity, where tragedies become fodder for symbolic sympathy without genuine accountability or adequate legal protection. Women have become “currency” in factional and regional conflicts – a dynamic clearly seen during the Suwayda massacres.

This reality raises larger questions about the meaning of justice in today’s Syria – how it has shifted from a fundamental right to a rare privilege. Rape is no longer an isolated crime but an indicator of deep flaws in the justice system and the state’s relationship with its citizens. Each assault carries unspoken messages: to women, that their bodies are unprotected; to communities, that armed power trumps law; to all, that justice is not a right but a privilege for the powerful or the well-connected.

Rwan’s case is not simply an individual crime but a condensed example of this reality. What is needed is not fleeting sympathy but tangible accountability targeting perpetrators and their enablers. Without it, every new crime will stand as a reminder that women’s bodies remain battlegrounds – and that justice’s absence persists until further notice.

This article was translated and edited by The Syrian Observer. The Syrian Observer has not verified the content of this story. Responsibility for the information and views set out in this article lies entirely with the author.