The stages now unfolding are increasingly clear. They begin with an initial phase of control: “soft” laws and administrative circulars that promote “moral values” as defined by those in power. In some cases, recommendations are issued instead of binding legislation. The goal is psychological conditioning—accustoming society to restrictions that will later harden into norms. Iran’s trajectory after the consolidation of clerical rule offers a telling precedent.

Syrian women’s struggle for legal justice spans decades. Their efforts focused on dismantling discriminatory structures, foremost among them the Personal Status Law—one of the most entrenched instruments of inequality. Reformers sought to eliminate discrimination, raise the minimum age of marriage, and secure guardianship rights. The challenge lay in the dense intersection of statutory law, Islamic jurisprudence, and prevailing social customs.

In its earlier form, the Personal Status Law governed the lives of millions while depriving women of guardianship over their children, denying them the right to pass nationality to them, and restricting access to divorce through onerous conditions. Men, by contrast, retained unilateral authority to dissolve marriage at will. The law codified multiple layers of legal and social discrimination. And although Syria acceded to the Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination Against Women (CEDAW) in 2003, it entered sweeping reservations on nationality rights, marriage, family relations, freedom of movement, and Article 16(2), which prohibits child marriage—citing incompatibility with Islamic law.

Women waited until 2019 for amendments setting the legal age of marriage at eighteen for both sexes, though judges retained discretion to approve marriage at fifteen with guardian consent and a finding of “interest.” The gradual dismantling of “honor crime” provisions culminated in 2020 with the repeal of Article 548, removing mitigating excuses for perpetrators and treating such crimes as ordinary homicide.

These were partial gains, and further reform remained urgent. Yet the fall of the Assad regime—widely seen as a chance to rebuild the social contract on more equitable foundations—has produced no meaningful horizon for women’s rights. Instead, it has exposed a troubling regression in gains that were already modest. The interim government sworn in March 2025 included only one woman among twenty-three ministers, a stark indicator of continued exclusion from decision-making. Soon after came attempts to regulate women’s bodies and presence in public space through a cascade of directives. Among them was Circular No. 284 from the director of Al-Mouwasat Hospital in Damascus, mandating gender-segregated seating—men in front, women in back—regardless of professional or medical status, all “in the interest of the public good.”

In this climate, the absence of comprehensive legislation protecting women from violence, forced marriage, and discrimination stands as one of the most serious institutional failures. Syrian women now find themselves forced back to the starting point of their struggle, as the state is rebuilt without them and the transitional phase unfolds at the expense of their rights, representation, and agency.

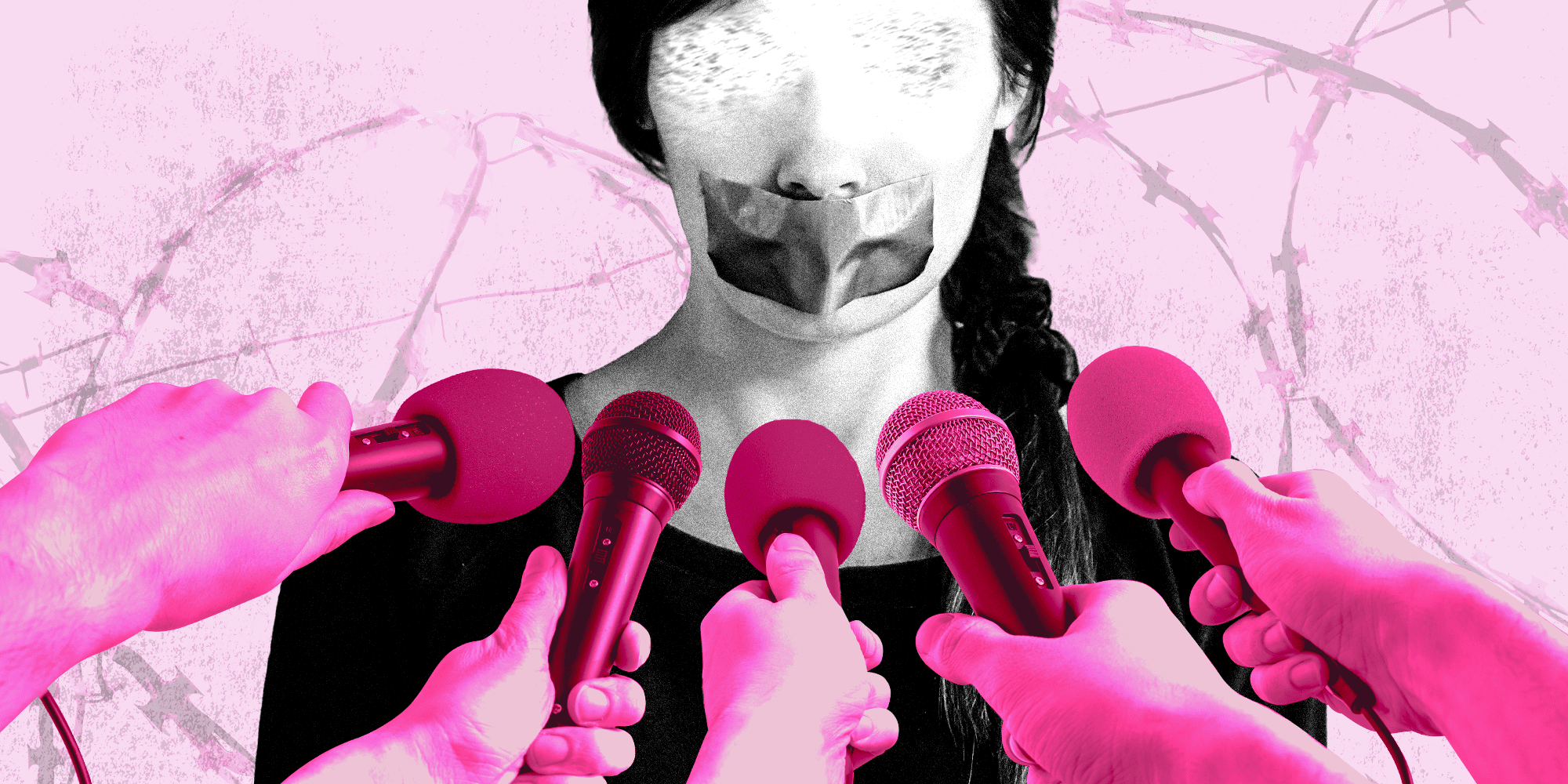

Exclusion from the Public Sphere

The few women occupying decision-making roles are widely perceived as instruments tasked with promoting the transitional government’s policies, adhering to its directives in exchange for remaining within its framework and amplifying its discourse. The Director of the Women’s Affairs Office, Aisha al-Dibs, publicly urged Syrian women not to exceed what she called their “God-ordained priorities,” confining their role to family and education. She further insisted that women’s organizations must align with the “model” the government seeks to construct.

As reports mounted about the abduction of Alawite women, the transitional government responded through a Ministry of Interior committee that denied the violations altogether, alleging instead that the women had eloped or left for economic reasons. The November 2025 report, steeped in insinuation, questioned the victims’ honor and familial commitment. A similar silence surrounded the abductions of Druze women following the massacres in Suwayda in July 2025. The Minister of Social Affairs and Labor, Hind Kabawat, issued no public condemnation.

A climate of complicity—sometimes tacit, sometimes overt—has turned authority into an active participant in manufacturing fear. Systematic abductions of Alawite women have occurred in full view of interim authorities, whether through denial, alleged involvement of affiliated elements, indifference toward armed groups linked to them, or neglect of abduction reports. In today’s Syria, women are dispossessed twice: first through forced disappearance, and again through the erasure of their victimhood and the imposition of humiliating narratives that blame them. Violence migrates from the body to the story itself, reshaping the victim according to the perpetrator’s script.

A Gradualist Strategy of Suppression

Authoritarian religious authorities often rely on psychological and social gradualism. Society is conditioned to absorb restrictions in stages: measures begin inside state institutions, extend into social life, and eventually acquire legal and constitutional force. The underlying objective is control over women and the consolidation of religious authority over society.

The pattern is familiar. It begins with “soft” regulations framed as moral guidance. Iran in 1979 encouraged female public employees to adopt the headscarf before mandating it by law. Afghanistan under the Taliban in 1996 first imposed restrictions in educational institutions before barring women from employment altogether. Experimental decrees follow, applied cautiously to avoid open confrontation.

In Syria today, similar steps are visible. A January 2026 directive from the Governor of Latakia banned female employees from wearing makeup during working hours. In June 2025, the Ministry of Tourism issued guidelines requiring women at public beaches and pools to wear modest swimwear, such as the burkini, citing “public taste and social sensitivities.”

Authorities then monitor public reaction across media and social platforms, softening language—framing measures as workplace regulation or moral protection—to dilute criticism and foster psychological adaptation. Resistance is measured; acceptance is assessed. The regulation remains in place and gradually becomes routine.

Escalation follows. More stringent decrees appear once society has been conditioned. This phase materialized in November 2025 with Justice Ministry Circular No. 17, implemented in December, restricting guardianship over minors exclusively to male agnates on the father’s side. Mothers, even custodial ones, are excluded as legal guardians. The implication is stark: mothers do not automatically possess guardianship over their own children.

Stabilization comes next through enforcement mechanisms and light sanctions. Over time, fines, professional exclusion, or restricted access to public spaces consolidate compliance. Ultimately, restrictions acquire symbolic and constitutional status, embedded in national identity. Iran’s post-1989 constitution enshrined mandatory veiling within its moral framework. Comparable regimes have elevated “social ethics” to constitutional sanctity, rendering critique tantamount to heresy.

This process is neither accidental nor episodic. It is a deliberate psychological and social strategy: gradual guidance, experimental decrees, daily monitoring and sanction, and eventual constitutional consecration.

Conclusion

Syrian women’s pursuit of a more just legal and social order now faces formidable obstacles. They confront a political authority seeking to entrench itself through religious and cultural legitimation, operating within a fragile society emerging from prolonged war and sustained by an increasingly aggressive propaganda apparatus. They also face segments of society eager to consolidate dominance over women’s bodies and presence in public life.

The struggle is no longer limited to legal reform. It has become a contest over the architecture of fear—over whether the transitional state will evolve into a republic of rights or into a system that engineers submission under the guise of moral guardianship.

This article was translated and edited by The Syrian Observer. The Syrian Observer has not verified the content of this story. Responsibility for the information and views set out in this article lies entirely with the author.