The United Nations says it needs more information on an agreement reached in the Kazakh capital of Astana last week to establish “de-escalation zones” in Syria before it can endorse it, a U.N. aid official said on Thursday.

The memorandum signed by Russia, Turkey and Iran came into effect on the weekend and calls for a truce — renewable after six months — between regime and opposition forces in four designated safe zones as well as the delivery of aid and medical supplies.

“Russia and Turkey and Iran explained to us today and yesterday … that they will work very openly, proactively, with United Nations and humanitarian partners to implement this agreement,” U.N. Syria humanitarian adviser Jan Egeland told reporters.

“We do have a million questions and concerns but I think we don’t have the luxury that some have of this distant cynicism and saying it will fail. We need this to succeed,” he said.

France’s ambassador to the U.N., François Delattre, questioned whether the U.N. has “all elements we need to understand the substance of the agreement and the way it is going to be implemented."

“The answer to this question is ‘not yet,’” he added.

Sweden’s ambassador to the U.N., Olof Skoog, said he hoped for more information before voting on the resolution.

“We want peace and stability and humanitarian access in Syria,” Skoog added.

Security Council members are expected to meet behind closed doors this week to discuss the terms of the deal. The three guarantors have until June 4 to establish the borders of the safe zones while details on who will oversee the cease-fires and aid deliveries is not yet clear.

“There will need to be effective monitoring mechanisms as well as full and sustained humanitarian access,” said a U.N. diplomat.

Implementing the deal would be “complicated,” the diplomat said.

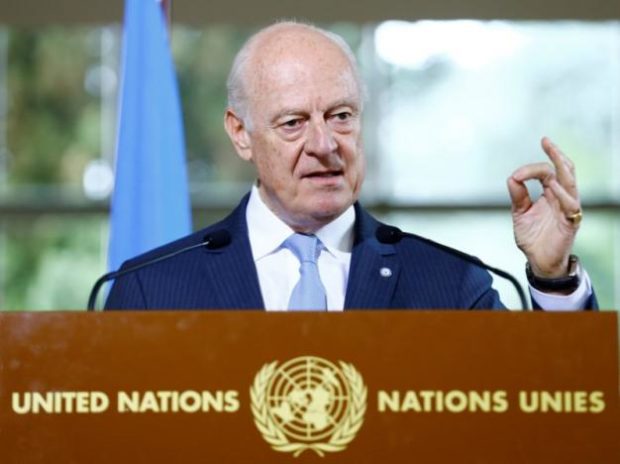

U.N. Syria envoy Staffan de Mistura said he was convening what he called “rather business-like, rather short” peace talks in Geneva from May 16-19 to take advantage of the momentum. The political weight of the signatories and the staggered timing of the deal gives it a strong chance of working.

A key aspect of the Astana deal was that it was an “interim” arrangement to address urgent issues, not a permanent partition of Syria, he said.

De Mistura said the Astana talks had also made rapid progress on agreements covering prisoner releases and de-mining, and both were almost complete.

Egeland said he could point to one concrete result from Astana: the reported reduction in fighting and aerial attacks. But aid convoys were only being allowed in at the rate of one per week, with no permission letters coming from the regime.

Although some recent local surrender agreements meant the number of people who were hard to reach with aid had fallen by 10 percent to 4.5 million, a further 625,000 were besieged – 80 percent of them by forces loyal to President Bashar al-Assad, he said.

This article was edited by The Syrian Observer. Responsibility for the information and views set out in this article lies entirely with the author.