Less than a month before the 9/11 attacks in 2001, Turkey’s Justice and Development Party (AKP) was born—on 14 August of that year. That political milestone would soon intersect with a seismic shift in American foreign policy, the reverberations of which still leave us parsing through a fog of contradictory accounts.

The AKP emerged from a broad alliance of conservatives and centrists—remnants of Virtue Party, Motherland Party, and the True Path Party—united more by what they rejected than what they embraced. Disillusioned by the traditional Islamist current led by Necmettin Erbakan, the founding members sought a new political formula. They disavowed formal Islamism, embraced free-market liberalism, advocated for EU membership, and rallied behind a glowing orange lightbulb as their party symbol—a youthful, reformist brand against an entrenched military elite and decaying political class.

Their first electoral victory in 2002, with just over 34% of the vote, allowed them to form a single-party government under Abdullah Gül. Within months, legal barriers were lifted for Recep Tayyip Erdoğan, who would assume leadership in March 2003—and hold onto it ever since.

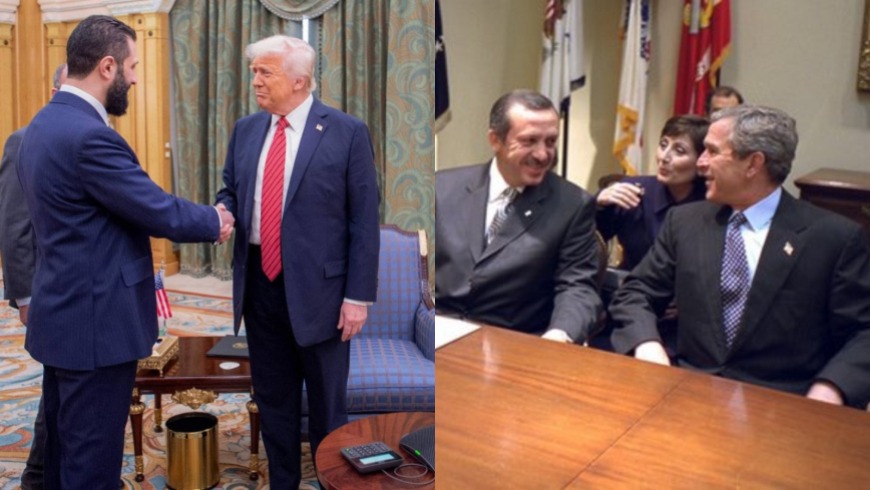

Before even taking office, Erdoğan was invited by the George W. Bush administration to Washington, where he met President Bush, Vice President Dick Cheney, Secretary of State Colin Powell, and others on 10 December 2002. The details of that meeting remain opaque—and perhaps always will. But what is certain is that Washington was preparing for war in Iraq and didn’t want Ankara to complicate the mission. Could Turkey have stopped the war? Not likely. Could it have delayed or obstructed it? Possibly. But that could have easily led to yet another military coup in Turkey, extinguishing the fledgling AKP experiment.

From Erdoğan in 2002 to Sharaa in 2025: Echoes and Parallels

Fast forward to 14 May 2025. A moment equally surreal and historic unfolded in Riyadh: Syrian Transitional President Ahmad al-Sharaa met with U.S. President Donald Trump, alongside Saudi Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman. The image—a former jihadist from the same ideological cradle that spawned 9/11 seated next to an American president who had once labelled him a terrorist—could easily be deemed the “photo of the year.”

President Erdoğan also joined the meeting—virtually—connecting the present to the early 2000s in a loop of geopolitical déjà vu.

One wonders: Did Sharaa, as a lost young man in Damascus years ago, ever imagine this moment? Did he see Erdoğan’s 2002 visit to Washington on Al Jazeera and realise how swiftly politics can pivot? Months after that visit, U.S. tanks rolled into Baghdad, and Sharaa himself, like many of his generation, rushed to witness the war firsthand—because hearing is never the same as seeing.

Did Sharaa revisit the lessons of U.S. foreign policy—the power wielded by Dick Cheney, arguably the most influential vice president in modern history, a man eerily similar to Trump in temperament and ideology? Cheney’s political ambitions were famously thwarted by his daughter’s public identity—costing him a shot at the presidency. But the Cheney legacy lives on, in the political instincts of Trump.

So, what exactly was discussed in the Riyadh summit among Trump, Sharaa, and Erdoğan? Iraq? Gaza? Trump’s hope for a Nobel Peace Prize? Or, like in 2002, was the real aim to “avoid disruption”?

The New Narrative: From Maps and Mandates to Mutual Respect

Following the summit, U.S. Special Envoy to Syria Thomas Barrack—a Lebanese-American fluent in Arabic and former ambassador to Turkey—issued a strikingly emotive and populist statement. After meeting Sharaa in Istanbul, Barrack declared that:

“A century ago, the West drew maps and mandates with ink, dividing Syria and the region through the Sykes–Picot agreement—not for peace, but for colonial designs. That division was a costly mistake. It won’t be repeated.”

He emphasized that the era of Western intervention is over. The future, he said, lies in partnerships rooted in mutual respect, not imposed borders or lectures delivered by foreign armies.

Barrack insisted that Syria’s tragedy stemmed from fragmentation, and that its rebirth depends on dignity, unity, and investment in its people. “We stand beside Turkey, the Gulf, and Europe—not with troops or sermons, but with collaboration and truth,” he said.

He added that the fall of Bashar al-Assad had opened the gates to peace, and that lifting U.S. sanctions would allow Syrians to pursue prosperity and security.

Reading America – Top to Bottom

Barrack’s language reveals much about how America wants to be understood. In diplomacy—as in literature—meaning lies not only in what is said but in how the message is structured.

In this phase of diplomacy, the winning formula is clear: align with those who read the message from the top down. Know the headline. Knock on the right door. Shake hands with calm confidence before asking to enter.

Barrack’s statement may read like a sentimental note, but it also signals a profound strategic pivot.

At 1600 Pennsylvania Avenue in Washington, the residence of the U.S. president, sits the author of this message—a letter with a headline, body, and seal. Only those who have read it carefully, who understand its syntax and subtext, will be permitted inside. In politics, when conditions are ripe—a victorious popular revolution, steadfast leadership, intelligent strategy, and a bit of luck—nothing is impossible.

In the end, whether you read from the top down or the bottom up, the message is the same: history may not repeat itself, but it certainly rhymes.

This article was translated and edited by The Syrian Observer. The Syrian Observer has not verified the content of this story. Responsibility for the information and views set out in this article lies entirely with the author.