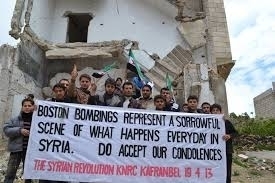

The inhabitants of the “liberated” regions don’t care about what has been happening recently in the general scene – they are accustomed to war and the daily lifestyle despite the difficulties and the scent of death and destruction everywhere – but the death of Ahmad, a five-year-old child in the lustrous village of Kafar Nubbul, pushed his father to join the Free Syrian Army.

Ahmad’s mother, Fadwa, is now busy all day and night saving bread, milk and vegetables for her three remaining children since she has no provider for months; her husband Ramadan went to fight against “Hezbollah militias and Assad’s regime forces” and never comes back more than once or twice a month to visit his family in one of Idlib’s villages in the north, near the Turkish borders.

Fadwa, who carries a secondary school certificate, is about 40 years old. At 20 she got married to Ramadan, who graduated from the engineering institute. They established a house with the help of their relatives and acquired a small piece of agricultural land which supported them in addition to the husband’s salary. Ramadan and Fadwa have three boys and a girl, who is the eldest among her siblings.

“Before the war our life was just like all Syrians’ lives,” Fadwa says to The Syrian Observer.“Financially, we were relatively self-sufficient. After the breakout of the revolution, we began to fear aircraft bombings because we couldn’t find a shelter in our region. My son Ahmad was killed in a raid while playing near his grandfather’s home. He was five years old. My husband Ramadan couldn’t bear the shock so he took up arms and joined the fight against the regime and since that day, like many daughters of my generation in the village, I await my husband’s visit and pray for him to come back alive, not as a corpse, and may God help us.”

A teacher who turned into a director of a well-known periodical said that “the people in the liberated areas founded a social solidarity system, but the idea is not ideal of course.”

Muhammad al-Salloum, who is the chief editor of al-Ghirbal newspaper, told The Syrian Observer that “the idea is not that ideal, but it is the best possible solution; a large number of families depend on aid or on what is available of agricultural crops based on the principle of food self-sufficiency.”

The most difficult thing is when people in the liberated villages are obliged to go to the governorate’s center to get their salaries because the regime restricted these places for them. Some of these people are wanted by some security branches, thus they don’t go there. And the result is they get fired from their jobs after a while. Fadwa is a good example; she hasn’t gone to collect her husband’s salary since he joined the fight. There are several other reasons people get fired, such as being accused of dealing or cooperating with the revolutionaries or being a relative of someone who is related to an unlawful party for example, or simply because of a report raised by unknown people or informants who are still dealing with the regime.

The way from Kafar Nubbul to Idlib costs 800 SP, while in most cases the salary does not exceed 15000 SP (the dollar was sold for about 205 SP at the end of June), Salloum says.

Food in general is available, but inhabitants suffer from the extreme rise of prices and not all of them are able to buy; thus they supply the shortage with their own land’s agricultural and animal products, because everything is being priced according to the dollar and doesn’t have a stable price. Salloum says that the Turkish goods exceed the Syrian ones in our markets because of the comparative ease of access; the way to Aleppo and Damascus, the source of goods, is dangerous or almost impossible.

Citizens rarely eat meat, Fadwa says. “I offer my children a meal that includes meat once or twice in a month. The prices are too high, but thank God for everything and may God help us.”

“As for water,” she adds, “which used to reach us once a week, it rarely reaches us now, because of the breakdown of the water network and the fact that no one has attempted to fix it.”

“The regime lets everything fall into ruin,” Salloum says. “Some villages which have water pipes running through them stole water and used it to water their crops, thus we get water from the old drilled wells for money and the price of a water tank reaches 1500 SP. This crisis caused an increase in the drilling of uncensored boreholes. The electricity could be cut for up to four or five consecutive days, and if it is available then the average hours of daily supply is about six hours.”

Mobile telecommunications were totally cut off after “the liberation” of Kafar Nubbul except in some elevated areas. Families who are trying to communicate with their sons gather together on a highland to use one of the two phone networks and near the town’s cemetery for the other one.

As for Internet and landlines, according to Salloum, the bombing destroyed the post office to prevent the civilians from benefiting from anything and it has been bombed again later with warplanes and now communications are cut off completely. “We depend on satellite Internet,” Salloum says, “which is widespread in our region. They use very expensive Turkish devices and recently providing internet through satellite communication has become an investment project for some people who established networks that cover a good area of the town.”

Money changers who deal with some major currencies such as the dollar, rial, Turkish lira and sometimes euro are now widespread because people often rely on the aid reaching them from abroad.

In Kafar Nubbul, cheese and other dairy products arrive from the nearby “also liberated” regions, while most vegetables and fruits are produced in the town; however, the lack of water makes it difficult.

“The regime bombs wheat fields to starve the people.” Salloum says.

Regarding the nature of the social relationships between the people of the village, Salloum, who is concerned with documenting life events there, says “Kafar Nubbul belongs to the Sunni sect and has no sectarian conflicts but suffers from people’s migration and receiving refugees from the nearby Sunni villages. The town’s population before the revolution was about 32,500; after the migration only 19,000 remained, but the number of the displaced persons living there now means the population exceeds 35,000. The relationships are normal in general; a quiet coexistence doesn’t prevent the criminal discomforts and problems imposed by the new reality of the town.”

“At the beginning of the revolution, the marriages were stopped utterly on the hope that they would be resumed at the end of the revolution that we thought would not last for more than a few months. However, because of the long time that has passed, some weddings happened in which a lot of the ceremonies were condensed and the attendance became limited to family visits for some relatives only. Brides’ preparations of gold and cloths have also been reduced because of high costs, and the engagement period has become shorter and doesn’t exceed a few weeks. The people are trying to adapt with all the developments.”

Assad's regime doesn’t exist in the town in any administrative form and most employees get their salaries at home since the liberation of the town. "My wife is an agricultural engineer in the agriculture directorate in Kafar Nubbul and since the liberation her workplace became a seat for a fighting battalion. Employees go to sign in at one of their houses, and at the beginning of each month they get their salaries from the regime who knows that they are not going to work. It seems that both sides know it but they laugh at each other," Salloum says.

But this doesn’t apply to the army and the police, as most of these have now defected and they don’t receive any salary or income except some simple help they get.

"There are some cases of extreme poverty in the town and you may find it strange if I told you that one of the reasons of migration to Turkey is – in addition to bombardment – poverty because people in the Turkish camps can at least provide for a man and his family's living,” Salloum says.

People get bread from the Kafar Nubbul bakery, which works irregularly, as sometimes there is no flour and other times there is no fuel to operate the bakery. Flour and fuel are provided by some international organizations and the quality of the bread is below standard because of the bad quality of the flour and carelessness and absence of control in addition to the decrease in temporary workers' wages by half or maybe to a quarter because of their intermittent work schedules.

The civil society in the town counts the losses and casualties as well as the damage to buildings and properties in a documented and practical way with the help of engineers and volunteer youth. They have gathered accurate statistics about the number of daily bread packages for each family and there is now a project to open a private bakery in the town. This has been funded by a Kuwaiti humanitarian organisation.

Kafar Nubbul is not the lost paradise and there are differences in visions among citizens; some want a civil state, some an Islamic one, but all agree on bringing down the regime first. The people are against extremism and fundamentalism. This was clear when al-Nusra tried to establish a base in the town and it didn’t succeed and was faced by the people's negative reaction and general condemnation.

But this can't be applied to all liberated areas. In Binnish, for example, it seems that extremists control everything. The reason for this is the failure of military and civilian rebels to provide any project to run the country as well as the poor financial resources, while extremists have enormous budgets. Some run after money wherever the fund may come from.

There are three private hospitals in the town and there is a big field hospital that serves the whole region. There is also the Orient hospital, which is being prepared now. A committe for emergencies has been established and their mission is to move the injured directly to Turkey for free. Medicine is insufficient and they compensate with some medicines from Turkey. Some doctors moved and some remained.

Schools have totally ceased operations. Some of them have been destroyed and others looted, and some others have been turned into military bases. We can't ignore people's worry about sending their children to schools because of the repeated bombardment. Students of ninth and twelfth grades haven’t had their examinations as they were held exclusively in the governorate's center, besides the fact that they have not attended school all year.

A disaster is forthcoming: there are children who are supposed to be in fourth grade and, to this day, know nothing about the alphabet and numbers.

......