Moscow’s Vnukovo International Airport was crowded with passengers awaiting their flights as Syrian President Ahmad al-Sharaa’s plane landed amid tightened security. The president arrived to meet his Russian counterpart, Vladimir Putin, at the Kremlin—apparently seeking to build stronger ties with a country whose relationship with the Syrian people has long been complicated.

It has been less than a month since Sharaa returned from the United States. While his trip to Washington was not an official state visit, it was symbolically significant: the first by a Syrian president to New York for the UN General Assembly since 1967.

From Washington, the leader of the Western bloc, to Moscow, the center of what remains of the Eastern camp—what exactly is al-Sharaa looking for in a country that was once Bashar al-Assad’s chief backer and helped prevent his downfall for more than a decade? Is this visit an attempt by Damascus to craft a new balance between East and West, or simply the result of political constraints and circumstance? And what does Russia want from Syria, and what does Syria expect in return?

Testing 320 Weapons in Syria

Only days earlier, Syria marked the tenth anniversary of Russia’s military intervention on September 30, 2015—an intervention that decisively shifted the war in favor of the Assad regime, caused massive displacement, and led to war crimes and crimes against humanity.

Syrians still recall Russian Defense Minister Sergei Shoigu’s boast that his army had tested more than 320 types of weapons during its operations in Syria.

In 2021, Shoigu said at the Rostvertol helicopter plant that the company had developed a new model based on lessons from combat in Syria. The goal of Russia’s weapons testing campaign was clear: to market its arms globally by showcasing them in real-world conditions.

Under the previous regime, Syria’s relationship with Moscow had turned into a model of total dependency—political, military, and economic. Damascus opened its doors to Russian bases and signed long-term agreements heavily favoring Moscow in exchange for its protection.

These agreements extended to economic and trade spheres through long-term, one-sided contracts and memoranda of understanding. One of the most notable was the 2019 deal granting the Russian company Stroytransgaz (CTG) a 49-year lease to operate the Port of Tartous.

In 2018, the same company secured a 40-year renewable concession to operate three fertilizer plants in Homs, effectively controlling Syria’s phosphate industry.

Militarily, Russia sought to preserve its foothold in the warm waters of the Mediterranean. In 2015, it signed an open-ended agreement allowing its air force to operate from Hemeimeem Air Base near Lattakia—soon becoming the hub of its military campaign. By late 2015, Russia had reinforced the base with air-defense systems and deployed military police.

In 2017, Moscow and Damascus signed two agreements granting Russian forces the right to use Syrian bases for 49 years, renewable for another 25.

The result: a steady expansion of Russian military and economic dominance in Syria since 2015.

Did Moscow Really Try to Save Assad?

Since its direct intervention in 2015, Russia was perceived as the main guarantor of Bashar al-Assad’s survival. That view persisted until the final days before Damascus was liberated, but reality proved more nuanced. While Russia’s military might could have tipped the balance, the Kremlin chose not to intervene decisively during the regime’s last battle.

Although Russian airstrikes continued until December 7, 2024, the eve of the regime’s collapse, their nature changed—they targeted empty areas, avoiding direct engagement with opposition forces. Many observers saw this as a signal that Moscow would not prevent a managed political transition if its own interests were preserved.

Leaks from Tehran suggested Iranian officials felt betrayed by Russia, while Turkey’s foreign minister later claimed Moscow had been capable of saving Damascus but “chose not to.”

It appears Russia concluded that Assad—and Iran behind him—had become liabilities to its regional ambitions. Facing growing Western pressure, Moscow preferred to reposition itself behind a new Syrian legitimacy, ensuring influence without the political or military cost of defending a doomed regime.

From that perspective, Russia treated the regime’s fall as an opportunity to redefine its role in post-Assad Syria rather than to die on his hill. It kept its bases and secured a place in Syria’s political future, while welcoming Assad himself to Moscow—along with his gold bars, billions of dollars, and a collection of luxury apartments near the Kremlin.

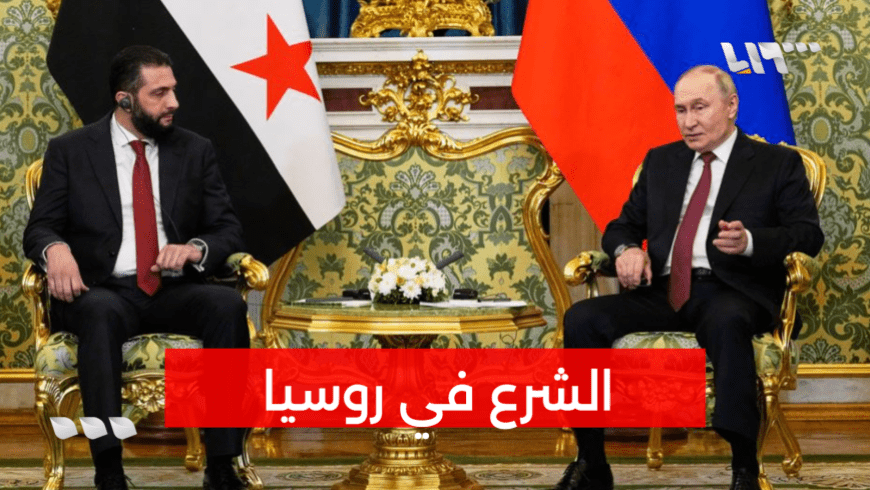

History Reversed: Sharaa in the Kremlin

Just 13 kilometers from the Kremlin, the deposed Bashar al-Assad now lives with his family and financial secrets in luxury apartments. From his balcony he cannot see the Kremlin, but he likely heard of President Sharaa’s visit—or saw the motorcade driving through southwest Moscow toward the red-walled palace under Syria’s new flag.

Inside the reception hall, Putin welcomed Sharaa in front of the Russian and Syrian flags. The Syrian delegation included Foreign Minister Asaad al-Shibani, Defense Minister Murhaf Abu Qasra, Intelligence Chief Hussein Salameh, and Maher al-Sharaa, the presidential secretary-general and physician who had lived in Russia, married a Russian citizen, and returned to Syria in 2022 after years in Turkey and Idlib.

The main headline of the day: Sharaa and Putin discussed re-calibrating Syrian-Russian relations and expanding joint projects.

According to Russian media, talks focused on economic cooperation, food security, and energy, stressing the importance of maintaining stability in Syria and the wider region and deepening the historic partnership between the two countries.

During the meeting, President Sharaa said Syria would seek to “re-adjust its relations” with Russia and underlined the need for stability.

“We are also connected by important bridges of cooperation, including material ones,” he said. “We will continue to build on them in the future to relaunch our comprehensive relationship.”

He noted that part of Syria’s food supply depends on Russia, adding:

“We are trying to redefine the nature of our relations with Russia. We respect all past and current agreements between our two countries. Many of Syria’s power plants rely on Russian support.”

For his part, President Vladimir Putin stressed that Moscow’s relationship with Damascus is historic and unique, saying Russia’s only goal had always been “to serve the interests of the Syrian people.”

“Our relations were never dictated by political circumstances or self-interest,” Putin said. “For decades, our objective has been the welfare of the Syrian people.”

He praised the recent parliamentary elections in Syria as “a major success” that would strengthen political cohesion, adding:

“I’m pleased to see you and welcome you to Russia. We are ready for regular consultations with Syria through our foreign ministries.”

The Key Question: What Does Each Side Want?

It is clear that Russia will not apologize for the atrocities committed in Syria, nor compensate victims, nor hand over Bashar al-Assad to justice—Moscow has never extradited an ally. The Syrian Network for Human Rights has documented Russia’s obstruction of international accountability by using its UN veto 18 times, including 14 since its intervention, and voting 21 times against Syrian victims at the Human Rights Council.

Between September 30, 2015, and December 8, 2024, Russian forces were responsible for the deaths of 6,993 civilians, including 2,061 children and 984 women, 363 massacres, and at least 70 killed medical workers (including 12 women) and 24 journalists. Russia also carried out 1,262 attacks on civilian facilities, including 224 schools, 217 medical centers, and 61 markets.

With Syria’s new geopolitical posture now internationally recognized, President Sharaa’s Moscow visit likely tackled several critical files:

• Security arrangement with Israel: Sharaa may discuss reactivating the 1974 Separation of Forces Agreement or crafting a new one granting Damascus political maneuvering room short of full normalization sought by Benjamin Netanyahu, especially after Israel’s recent strike on the Defense Ministry in Damascus and ensuing unrest in Suweida. Sharaa hinted at a possible deployment of Russian military police along the border.

• Iranian influence in Syria: Talks are expected to define the limits of Tehran’s role, which Moscow had shielded politically and militarily in past years—especially after Qassem Soleimani’s assassination and the rollback of Iranian presence following the “Deterrence of Aggression” operation at the end of 2024.

• Justice and accountability: The Syrian delegation might formally request Russia to hand over Bashar al-Assad and other ex-officials residing there, as part of Syria’s transitional justice process—though this is highly unlikely given Moscow’s history of sheltering ousted allies.

Among those exiled in Russia:

• Eduard Shevardnadze, Georgia’s president, ousted in the 2003 Rose Revolution

• Askar Akayev, Kyrgyzstan’s first president, deposed in 2005

• Viktor Yanukovych, Ukraine’s president, who fled in 2014

• Bashar al-Assad, Syria’s ousted president, toppled in 2024

• Military and economic files: Topics reportedly include the SDF, the Russian military police presence at Qamishli Airport, modernization of Syria’s new army, the future of Russian bases on the coast, existing agreements from the Assad era, grain supplies, and currency printing.

• Security coordination and counter-terrorism: Damascus wants to maintain cooperation with Moscow against ISIS cells in the Badia Desert.

A New Balance Map

The new Syrian state aims to establish a balanced relationship with Moscow—based on mutual interests rather than subordination—within a foreign-policy doctrine of zero problems with both regional and global powers. Damascus is trying to anchor itself between the Western bloc led by the U.S. and Europe and the Eastern bloc represented by Russia and China.Syria is betting that this visit will mark the start of a new strategic partnership with Moscow, complementing its recent opening to Washington after Sharaa’s meeting with U.S. President Donald Trump—a foreign-policy strategy guided by pragmatism and national interest above all else.

This article was translated and edited by The Syrian Observer. The Syrian Observer has not verified the content of this story. Responsibility for the information and views set out in this article lies entirely with the author.