In 2023, Turkey marked the centenary of its republic, founded under the stern leadership of Mustafa Kemal Atatürk. The occasion revived a longstanding and unresolved struggle: the contest between secularism and political Islam, modernity and tradition, the founding myth of the republic and the counter-narrative that seeks to replace it. Turkey’s story over the past hundred years has unfolded as a dialogue between two men who never met. One was a soldier of austere discipline, who raised a secular republic from the ruins of a fallen empire. The other, a charismatic politician, strives to reclaim the nation’s Islamic legacy and reshape its political future.

This “dialogue of ghosts”, as some Turkish writers have termed it, may be uniquely Turkish in character, yet it reflects a broader scene familiar across the Middle East. More than one Arab republic stands at a similar crossroads: ageing regimes nearing twilight, new forces seeking to claim their legacy; centralised, secular states confronting populist movements rich in religious rhetoric; leaders vowing to turn the page on decades of failure and repression.

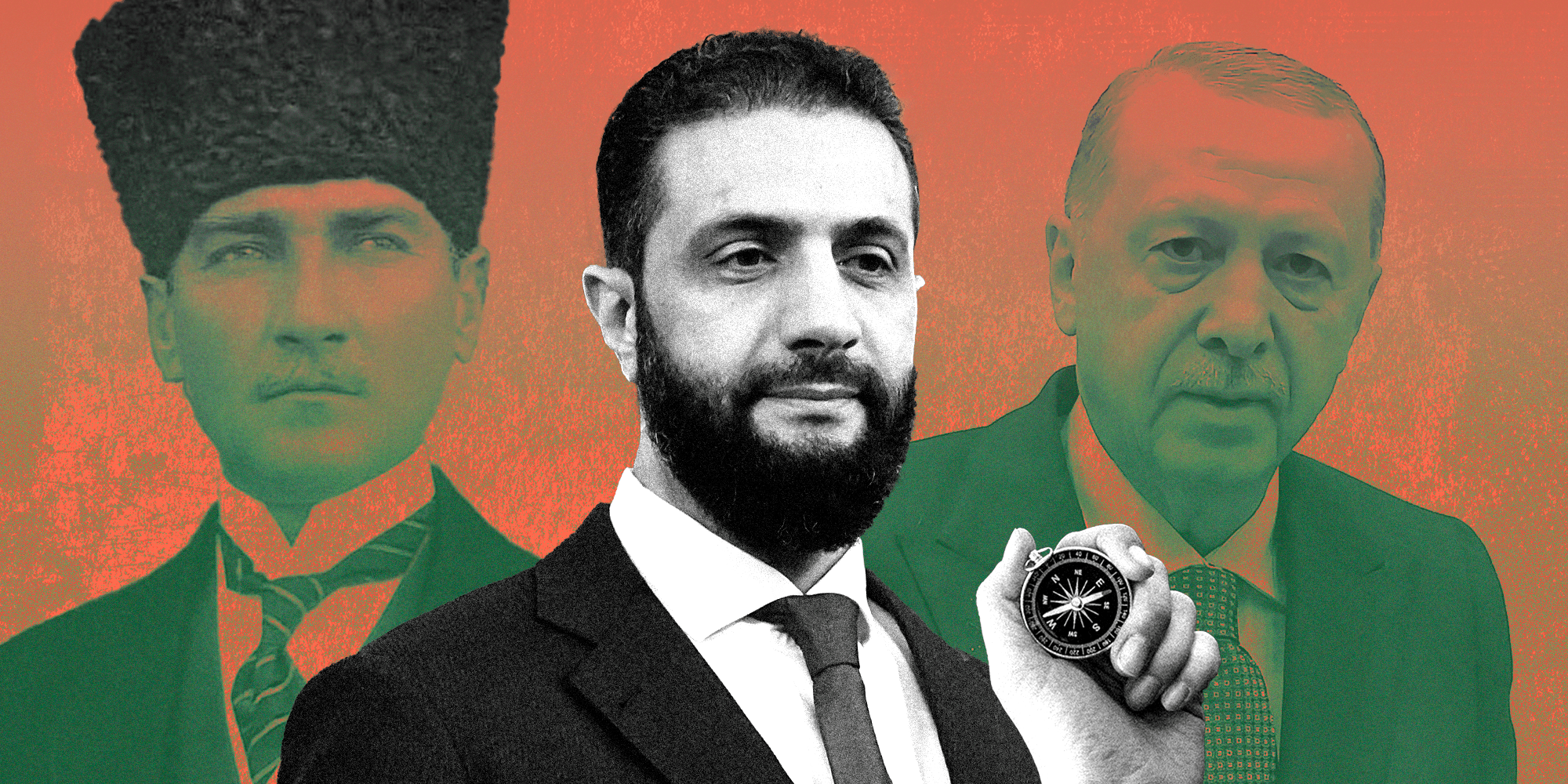

Nowhere is this tension more vividly illustrated than in Syria after Assad. President Ahmad al-Sharaa, tasked with rebuilding a nation ravaged by dictatorship, war and foreign occupation, faces the same ideological crossroads that shaped Turkey’s modern century. Two paths lie before him. One draws inspiration from Atatürk’s project of pragmatic, outward-looking modern statehood. The other mirrors Erdoğan’s model, combining religious legitimacy with populist politics and centralised power.

Yet Syria is not Turkey. Sharaa’s moment is more fragile, more precarious. The nation he now leads is weaker, more diverse, with deeper wounds and sharper divisions—though perhaps also with a keener political awareness. The Atatürk–Erdoğan dichotomy cannot simply be transplanted. Syria cannot afford to swing between secular despotism and religious majoritarianism. Another possibility presents itself: the “narrow corridor” described by economists Daron Acemoglu and James Robinson—a third path that neither Atatürk nor Erdoğan fully realised. It imagines a state strong enough to enforce order, yet sufficiently constrained to nurture liberty and pluralism.

To grasp the significance of this choice, one must return to the Turkish struggle itself.

Two Visions of Turkey: A Century of Contestation

Atatürk: The Founder as Revolutionary Leviathan

Mustafa Kemal Atatürk stands among the towering figures of the twentieth century. From the ruins of a collapsed empire, he forged a new republic through an uncompromising programme of secular modernisation. He abolished the caliphate, replaced the Ottoman script, banned traditional attire. He centralised education and recast Turkey’s national identity with a Western orientation.

Atatürk viewed religion as a relic of backwardness and saw Westernisation as a civilisational imperative. His reforms were revolutionary and often authoritarian. The republic was not born of negotiation but imposed from above. The state became the engine of transformation, with society carried along as a reluctant passenger.

Erdoğan: The Rival as Counter-Revolutionary Leviathan

Recep Tayyip Erdoğan entered the political stage as Atatürk’s antithesis. Emerging from conservative quarters long marginalised by Kemalism, he rose through local politics to embody the resurgence of identity politics against the secular centre. His Justice and Development Party (AKP) promised to restore dignity to the religiously devout, broaden economic opportunities, and loosen the secular elite’s grip on power.

For a decade, Erdoğan pursued reformist policies while simultaneously attempting to rewrite the republic’s founding myth. He reconverted Hagia Sophia into a mosque, curtailed the military—the bastion of Kemalist orthodoxy—centralised authority in the presidency, and adopted a “neo-Ottoman” foreign policy stretching from the Balkans to Syria. Through his vision of a “Turkish Century”, Erdoğan has sought to construct a new foundational narrative aimed at supplanting Atatürk’s legacy.

The Pendulum: From Secular Despotism to Religious Populism

Shortly before his death, Fouad Ajami visited Istanbul during the Gezi Park protests of 2013. There, he observed the cultural fault lines cleaving Turkish society. In the cafés of Bebek overlooking the Bosphorus, portraits of Atatürk fluttered beside Turkish flags, a symbol of confidence in an urbane, secular community. Across the city in Taksim Square, Erdoğan’s police pursued young demonstrators defending one of the last public spaces in a metropolis reshaped by a resurgent Ottoman impulse. Ajami saw in this tableau a profound division over the republic’s identity and the direction of its future.

The American writer Eliot Ackerman, a specialist in Syrian and Turkish affairs, described Turkish politics as an unceasing pendulum—swinging between the rigid secularism inherited from Atatürk’s military state and the populist religiosity embodied by Erdoğan and his followers. Neither model, he argued, succeeded in achieving a lasting equilibrium. Secularism, when dominant, constricted religious practice; political Islam, when ascendant, undermined pluralism and threatened institutional independence. Thus, the republic remained, in Samuel Huntington’s phrase, a “torn state”, perpetually searching for a stable definition of itself.

This unresolved conflict distils the essence of Turkey’s political legacy—and through it, Syria’s dilemma becomes sharper still. States built upon a singular, closed narrative—whether secular or religious—carry within them the seeds of fracture. Such structures begin to crack when the balance of power shifts, or when communities find themselves excluded from a national story that denies their place. Turkey’s experience offers a clear lesson: identities imposed from above cannot withstand the tides of social transformation, and the overwhelming triumph of one model inevitably comes at the exclusion of the other.

In Syria, the problem is even more acute. Turkey, despite its deep social and political divisions, retained a functioning state, a cohesive army, and a competent administrative system that enabled it to weather crises. Syria, emerging from decades of autocracy and the wreckage of war, lacks the institutional scaffolding to protect it from collapse or to enable a balanced transition. Any project grounded in the supremacy of one side—whether in the image of a “Syrian Atatürk” enforcing a new secular order, or a “Syrian Erdoğan” shaping a state defined by religious character—would only replicate the conflict, perhaps in more severe form.

The Turkish experience offers Syria a vital lesson: when grand identities are deployed as political tools, they divide more than they unify. Syria’s challenge is not to choose between two inherited models, but to transcend the binary altogether—to construct a national formula founded not on the dominance of one vision, but on a balance that accords each component its rightful place within a shared state.

Syria After Assad: A Leader Between Two Models

Ahmad al-Sharaa inherits a country where the old order has collapsed without a new consensus taking shape. A rebel compelled to become a statesman, a former jihadist now speaking the language of diplomacy, he awoke one morning to find himself a leader navigating a treacherous path among communities scarred by war and steeped in mistrust.

As Erdoğan emerged two decades ago from the margins of political life, so too did Sharaa rise from the heart of the Islamic insurgency that defied Assad’s rule. And as Atatürk assumed, a century earlier, the mantle of a republic rising from ruins, Sharaa today bears the responsibility of rebuilding a shattered homeland. This duality exposes him to two opposing temptations.

The Temptation of Atatürk: Constructing a Modern and Powerful Civil State

President al-Sharaa could choose to concentrate authority, forge a civic identity, harness the institutions of the state to modernize society, contain religious groups, and secure stability through a disciplined administrative apparatus. Many Syrians, weary of war and yearning for the rule of law, order, and the certainty such a project might provide, would welcome this path.

Yet the Atatürkian model carries the peril of sliding into authoritarianism. A rebuilt Syrian state might revive the repressive reflexes that marked Baathist rule. Secularism imposed from above could alienate broad religious constituencies, as it once did in Turkey.

The Temptation of Erdoğan: Building the Nation on Populist Religious Foundations

Alternatively, al-Sharaa could draw upon his revolutionary legitimacy, deepen his Islamic roots, and establish a political order that makes Islamic identity the moral cornerstone of the new state. In this scenario, he would present himself as the leader who restored dignity to the Sunni majority and reclaimed Syria’s “authentic cultural identity” after decades of Baathist secularism.

This path, however, is fraught with the dangers of majoritarian despotism in the Erdoğan style. Electoral mechanisms may be preserved in form, yet their substance reshaped by institutions gradually bent to the will of the ruling movement. Under such a trajectory, pluralism recedes from the periphery toward the center, and minorities—religious, ethnic, and political—begin to feel that the state no longer serves as a common framework but as an instrument of a single social bloc. Alexis de Tocqueville warned of this “tyranny of the majority,” the moment when a democratic majority transforms into a force that regards its choices as the sole truth, redefining national identity in ways that exclude or diminish others.

In such a model, the façade remains democratic, but the deeper structure of the political system inclines toward concentrated power and the subjugation of all surrounding institutions. Ballot boxes become less a mechanism of alternation or accountability than a means of reproducing rule. Over time, the space for dissent contracts, diversity is recast as a threat rather than a value, and the state loses its capacity to embrace its natural pluralism. Marginalized communities, stripped of confidence in the worth of participation, withdraw from the civic sphere altogether. History teaches that both models, secular and religious alike, tend inexorably toward authoritarianism.

Why Neither Atatürk nor Erdoğan Suffices for Syria

Turkey’s experience illustrates that founding myths, once ossified into rigid orthodoxy, inevitably provoke cycles of backlash and reprisal. The secular republic built by Atatürk fuelled Erdoğan’s rise, and Erdoğan’s Islamic republic rekindled nostalgia for Kemalism. Neither succeeded in establishing a durable equilibrium between state and society.

Syria cannot afford to replicate this pendulum. Its demographic makeup is more diverse, its institutions far weaker, and its social wounds far deeper. Imposed secularism would provoke fierce resistance; religious hegemony could once again fracture the nation. Syria therefore requires a political model not aimed at vanquishing its adversaries, but at coexisting with them. Here, the concept of the “narrow corridor” becomes not merely an option, but an imperative.

The Narrow Corridor: A Third Path for al-Sharaa and for Syria

The theory of the “narrow corridor”, as articulated by Daron Acemoglu and James Robinson in The Narrow Corridor, offers an answer to Hobbes’s enduring dilemma. Hobbes held that only a mighty Leviathan, unchecked by constraint, could suppress anarchy. Revolutionary liberals, conversely, argued that society must prevail over the state. Yet history has shown both views to be incomplete: the absolute state degenerates into tyranny, while the unrestrained society descends into mob rule.

Freedom arises only when state and society develop together, each checking the excesses of the other through constant tension. This ongoing struggle defines the “bound Leviathan”. Such must be Syria’s path—neither Atatürk’s secularism nor Erdoğan’s Islamism, but something altogether different.

What conditions could enable Syria to build a bound Leviathan? Despite its traumas, Syria retains certain assets that may permit entry into this corridor. After more than a decade of mobilisation, resistance, and self-governance, Syrian society is now more politically conscious. The populist currents of social media can obscure deeper civic experiences and local networks that reflect a genuine appetite for political participation. Communities have acquired a political will that can no longer be marginalised. In parallel, Syrian diasporas abroad have grown increasingly influential, shaping public discourse and civic activism.

The transitional state, while too weak to dominate the country in its entirety, remains essential. Yet its leader can only govern by negotiation, consensus and a recognition of institutional limitations dictated by circumstance and the prevailing balance of power. Syria’s fragile state on one hand, and its war-hardened society on the other, make this narrow corridor not only viable but indispensable. The question is whether al-Sharaa will seize the moment.

Al-Sharaa’s Choice: Founding a Bound Republic or Repeating the Cycle

Should al-Sharaa govern in the style of Atatürk, Syria may attain stability, yet risks reverting to authoritarian rule. Should he emulate Erdoğan, he may win temporary loyalty, yet alienate wide constituencies and reignite conflict. Both paths lead to relapse—perhaps even collapse.

The bound Leviathan offers a third way, one that empowers the presidency even as it curtails its reach. This model would require Ahmad al-Sharaa to restrain his own authority, to permit the judiciary to overturn his decisions, and to enable decentralisation and local governance. He must share power with Syria’s diverse communities—Christians and Muslims, Sunnis and Alawites, Kurds and Druze, the devout and the secular alike. He must place the military under firm civilian oversight, nurture an independent press and civil society, and embrace political pluralism, even at personal cost.

This path is not that of the heroic founder nor the charismatic saviour. It is the path of the constitutional statesman—one who understands that liberty and stability emerge not from the triumph of an individual, but from his willingness to restrain himself and uphold common rules.

If al-Sharaa succeeds, he will be neither Syria’s Atatürk nor its Erdoğan. He will be something greater: the founder of Syria’s Third Republic—a republic safeguarded from its rulers, rather than subjugated by them. In doing so, he will claim his place in history, as great nations have done before. If he fails, Syria risks falling back into the Turkish pendulum, but with even greater fragility.

Modern Syria’s independent history may, with some licence, be divided into three phases: the pre-Baath era; the Baathist and Assad period; and the present moment. This third phase is both the pivot of hope and the axis of destiny. If al-Sharaa can break decisively with the past, Syria may begin to lay the foundations of a new republic—one rooted in values aligned with the spirit of our time. If not, the country will remain, at best, a “second and a half”: an unfinished project and a bitter disappointment to most Syrians, including al-Sharaa’s own supporters.