“Damn this bite of bread.”

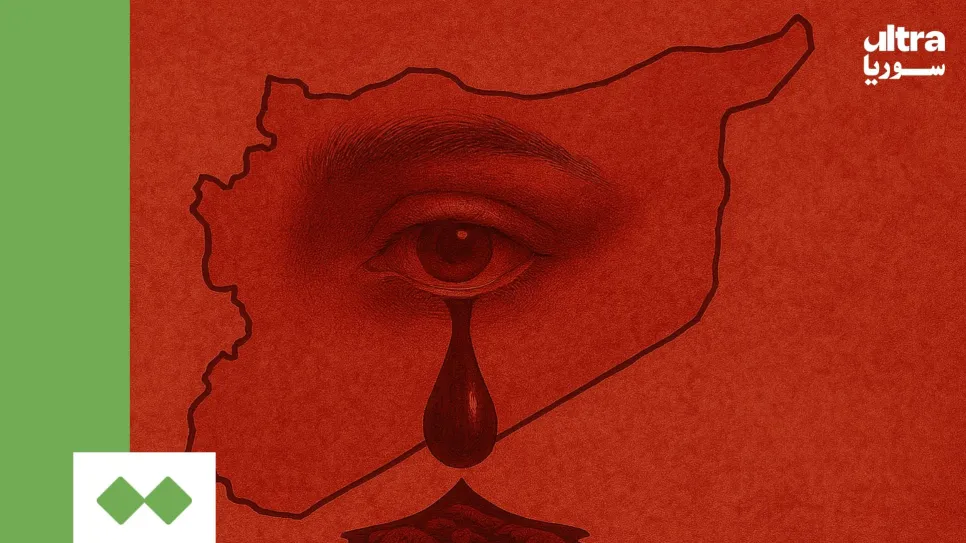

It is not the first time that young men have been targeted on sectarian grounds across Syria’s bloodstained landscape—and it will not be the last.

The local authorities—namely the Ministry of Interior and the Internal Security Directorate—remain silent in the face of a sectarian crime that claimed the lives of four young men. Four young men—repeated for emphasis—were assassinated on their way home from work, travelling from the Houla region to the village of Jadrin in western Hama. The details are now public, but the concern lies not only in the crime itself, but in the authorities’ handling of it, exposing the fragility of Syria’s so-called “security stability”. Let us be frank: this “stability” has been precarious for over a decade—both within Syria and across its fractured diaspora.

This is not the first time young men have been targeted for their sectarian identity since the fall of the “eternal regime” late last year. Nor, by all indications, will it be the last. The local authorities’ approach to transitional justice has been marked by unprecedented dilution, while families continue searching for their forcibly disappeared loved ones amid a rising death toll and the shifting dynamics of Syria’s conflict.

No official media outlet has reported on the incident, even as villages across the Homs and Hama countryside have entered a phase of protest and strike. Local accounts agree: the four victims—three of them from the same family, all Alawite—were ambushed with light weapons by unidentified assailants on motorcycles at the village entrance. Following the sectarian killing, internal security forces were quickly deployed to the area. Eyewitnesses also report that the checkpoint at the village entrance had been withdrawn several days earlier.

Jadrin, a small agricultural village with a population of 1,215 according to the 2004 census by Syria’s Central Bureau of Statistics, is surrounded by fields and plains. Most families rely on farming and manual labour. Despite its remoteness from major cities, it has found itself at the heart of sectarian shifts and civil strife—transformed from a quiet rural enclave into a bloody stage reflecting Syria’s broader tragedy.

There are no verified statistics on massacres targeting Alawites nationwide, nor on their displacement from the suburbs of Damascus under the banner of “restoring rights to original owners”—a slogan masking demographic engineering. Not far from the capital, the flour crisis in Sweida erupted following a sectarian massacre, turning the province into yet another flashpoint on Syria’s volatile map. From west to centre to south, we live a distorted reality—as though we are the generation inheriting the defeat of June 1967. To quote poet Imad Al-Junaidi (1949–2017) from his poem “Sweat… Sweat”:

A homeland narrows and closes in… a horizon overflows and collapses.

The voice of the grieving mother still echoes in my ears from the first time I saw the viral video. I admit—I tried not to watch it more than once. But it lingered, like the face of Rawan (20), whose official account of her rape by two human monsters in northwest Hama, specifically in the village of Hourat Amourin near Salhab, I could not ignore. The mother’s voice rings out:

“Damn the bite of bread you died for.”

Between her cry and the image, visions of armed gangs disguised as “unknown assailants” flash through my mind.

Transitional Syria—once envisioned as a space of hope—now appears hostage to political deals and investment interests. And the voices of grieving mothers ring truer than any government statement.

From the UN podium—the same one that failed to halt Israeli massacres in Gaza over the past two years, failed to condemn the most brutal physical and psychological assault on Lebanon, and turned a blind eye to the silent occupation of southern Syria—Western media celebrated the appearance of President Ahmad Al-Shara, the first Syrian head of state to address the UN since 1967.

He spoke of “mercy, goodness, and the triumph of forgiveness” in the battle to “repel aggression”. That message, I believe, was clear to anyone following the two days after 8 December—the day the eternal regime fell—far from the viral clips of vengeance against Assad-era symbols. But on the ground, once again, the so-called “fragile stability” has only deepened the rift among Syrians of all sects and creeds—a phrase borrowed from Abu Bakr Ahmad Al-Shahrastani. Here lies the chasm between imagined reconciliation and fractured reality. The social wound widens instead of healing, and talk of stability feels like an attempt to soothe a wound that refuses to close.

The local authorities continue to cling to the absence of any clear mechanism for transitional justice, rushing from one massacre to the next while promoting investment galas. Millions in capital flow into the country, alongside countless memoranda of understanding, in a scene that reveals a dangerous disconnect between official economic rhetoric about recovery and growth, and a bloody reality that renders those investments meaningless—mere window dressing for international optics.

In light of these violations—and I hesitate to call them mere “violations”—what kind of recovery is possible in a country drowning in blood? How can money rebuild shattered trust in a diverse society when the wounds remain open and justice is absent? Transitional Syria, meant to be a space of hope, is now a hostage. And the voices of grieving mothers ring truer than any government statement. Between the promises of recovery and the reality of roaming massacres, the contradiction is stark. A country bleeding in the present, with a future charted by uncertainty.

Finally, testimonies from the coast after the March massacres revealed the economic and social fragility of Alawite villages: impoverished homes, a near-total absence of services, and a pervasive sense of abandonment and betrayal. These communities are still reeling from a wave of mass killings that claimed over 1,500 civilian lives, triggering displacement towards Lebanon amid a weak humanitarian response. Local and international calls for investigation and accountability persist. The facts show that environments long exploited for their symbolic and security value have been left without protection or compensation. The persistence of impunity only deepens poverty and perpetuates cycles of revenge.

This article was translated and edited by The Syrian Observer. The Syrian Observer has not verified the content of this story. Responsibility for the information and views set out in this article lies entirely with the author.