Syria is charting a new economic path after the lifting of European sanctions, a move widely perceived as the natural successor to Washington’s landmark decision to ease its economic restrictions. This dual lift signals Syria’s reintegration into the international market and a pivotal turn toward a liberalized, neoliberal economic model championed by Syria’s transitional president, Ahmad al-Sharaa.

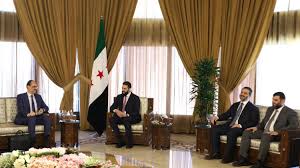

In his most recent speech, President Sharaa issued a direct invitation to international and regional investors to enter the Syrian market and participate in reconstruction, heralding a phase of broad economic openness. With more than 90% of Syrians currently living below the poverty line—and over 30% under extreme poverty by global standards—the appeal to foreign capital is less an option and more a necessity. Years of economic suffocation under Assad’s rule, compounded by Western sanctions and regional isolation, have left Syria in dire need of structural revival.

As part of this transition, Syria has announced plans to print its national currency in the UAE and Germany, moving away from previous reliance on Russia. This shift underscores a broader realignment in Syria’s geopolitical and economic partnerships, distancing itself from Moscow in favour of Gulf and European investors. A recent $800 million agreement with Dubai-based logistics giant DP World to develop the port of Tartus exemplifies this pivot—signalling an exclusive future for Western-aligned investment, notably absent of Chinese and Russian influence.

Yet, while this shift toward economic liberalism may appear inevitable, it is not without significant risks. Without a regulatory framework to ensure developmental priorities, Syria risks falling into a pattern of dependency on large-scale foreign capital. Lebanon’s post-civil war experience serves as a cautionary tale: the glitzy rebirth of Beirut masked an unsustainable economy built on speculative real estate and bloated banking services, ultimately culminating in financial collapse in 2019. In contrast, Rwanda offers a different template—one grounded in agriculture, education, and health, which helped stabilize and grow its post-genocide economy.

Syria, too, has a set of genuine opportunities. Beyond its strategic location and natural resources, it boasts a large diaspora of skilled professionals, a resilient core of domestic experts, and a political leadership now willing to pivot. However, turning these assets into sustainable progress requires more than optimism. It demands a cohesive national economic vision built on production, not rent-seeking; accountability, not cronyism; and a genuine partnership between state institutions, the private sector, and civil society.

Discussions have even floated the ambitious possibility of adopting a Singapore-style model for Syria. But such a transformation will be impossible without prioritizing the revival of agriculture and industry—sectors that are essential not just for job creation, but for achieving food and economic sovereignty. Moreover, Syria must dismantle the vast war economy networks—smuggling rings and black markets—that have flourished unchecked over the past decade.

The experience of post-Soviet states in the 1990s further highlights the potential pitfalls. Many underwent rapid “shock” privatization, where strategic national assets were sold off at rock-bottom prices to external buyers or domestic elites, birthing powerful oligarchies and stripping the state of its economic sovereignty.

To avoid a repeat of these mistakes, Syria must proceed with caution. The current phase presents the contours of both successful and failed models. Just as the nation is redrawing its political compact, this is a rare—and overdue—chance to write a new economic contract: one that safeguards sovereignty, demands accountability, and delivers on the long-deferred promise of social justice for all Syrians.

This article was translated and edited by The Syrian Observer. The Syrian Observer has not verified the content of this story. Responsibility for the information and views set out in this article lies entirely with the author.