“Several months ago, we documented the murder of two young girls from Qudsaya, Damascus Suburbs; their parents killed them because Syrian regime forces had raped them,” said Ameer, a member of Violations Documentation Center in Syria who is among those responsible for the center’s online database.

According to Ameer, this incident was documented in the framework of secondary violations committed by society against women who were raped by regime forces, either in prison or during the regime’s ongoing raids. Learning of and verifying such incidents is no easy task, as the families of rape victims fear discussing it, and even the victims themselves are secretive when it comes to society’s reaction to a crime that was forcefully committed against them.

A March 2014 report by the Euro-Mediterranean Human Rights Network also touches on the secondary violations against rape victims: “In Syria, women who are raped or sexually assaulted are stigmatized by society. In most cases, the women prefer to remain quiet out of fear being shunned by family members or of falling victim to an ‘honor crime.’ Additionally, there are serious implications to sexual assault against women, protective services are nearly nonexistent, and even when they are available, the family of a rape victim often prevents her from benefitting from such services to avoid stigma. Because of this, it’s difficult to obtain statistics on the survivors of rape.”

It is clear when speaking to any Syrian woman who was assaulted or raped — assuming she agrees to talk — that only half of the story is being told. The tale never ends with rape; it continues with society’s punishment, which is rarely more merciful than the violent crime itself, as if the woman had a say in what had befallen her.

The Syrian reality is made more miserable by the fact that, instead of directly dealing with the rape of their daughters, many families choose to displace the victims, forcibly marry them off, deny them of inheritance, disown them, or even kill them.

“I was not the only one fated to be assaulted and raped, this is a reality that many women in the regime’s prisons face, regardless of their ethnicity or place of origin,” said Layal, speaking from her own personal experience.

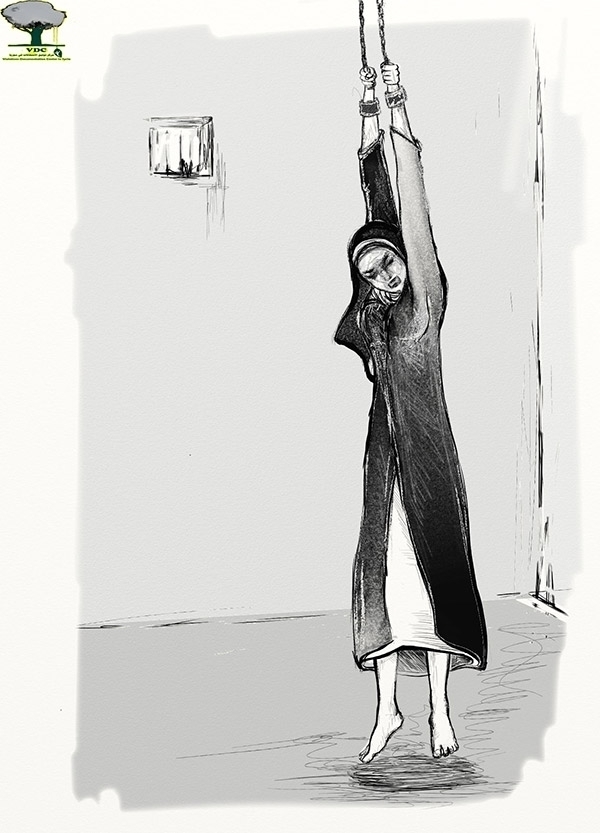

Layal al-Homsi is a young Syrian woman who was beaten, tortured, harassed, and orally raped multiple times by officers and interrogators at a regime prison after she was arrested for providing humanitarian assistance to families in need. Not surprisingly, Layal’s experiences have had a great psychological impact on her.

Layal comes from a revolutionary family from the city of Homs. She was arrested in Damascus on November 8, 2012 and was accused of a number of things, including being a conspirator in bombings that took place in Qazaz, Damascus and al-Mal’aab, Homs. She was eventually released from prison on January 1, 2013 as part of a prisoner swap between regime and opposition forces, when the regime released a number of female prisoners in exchange for Iranians who were being held captive by the opposition. After her release, Layal left Syria for Turkey because the Assad regime was trying to re-arrest those who had been released in the deal.

“After I was released from my 63-day detainment, my parents and community greeted me with pride because I had been arrested due to my revolutionary activities,” said Layal. “I did not tell any of them what happened to me when I was in prison, because as soon as I told my mother only that I was strip searched — the simplest act that I was subjected to — she went crazy.”

“I later tried to talk to one of my friends about what had happened, since I was having trouble coping with the torture and sexual abuse I had been through,” Layal continued. “But my friend silenced me and told me not to tell anyone about what had happened, because, as she said, it would hurt my reputation in our Eastern society. I was trying to get a job at a coffee shop when the owner kicked me out because he learned that I was a former detainee. Since then, I have kept quiet, repressing memories of what happened to me, which is extremely difficult. I try not to show my parents that I’m suffering so that they don’t ask me for details, forcing me to elaborate on what I went through.”

Layal is not alone in what she has endured; there are many Syrian women with similar, or even worse, stories, including Ayda, Khuloud, Lamya, and Leenah, whose stories are documented in great detail in a November 2013 report by the Euro-Mediterranean Human Rights Network.

Barbie, an anti-government activist who works to documents violations, said that one family in Hama city disowned their daughter upon learning that she had gone insane while detained in the regime’s Military Security branch and might have been sexually assaulted.

Naturally, these types of reactions impact the psychological wellbeing of women released from prison. While they may expect to be greeted with warmth by their communities after being subjected to oppression by government forces, reality isn’t always so kind, making life even more painful for these women. “Destruction, complete emotional destruction in all aspects,” is how Layal described about the psychological impact she’s facing as a result of her imprisonment and people’s treatment of her after her release.

“Because of what I endured when I was in prison in terms of abuse and rape, in addition to the unbearable conditions inside the prison, I am now not even open to the idea of getting married,” Layal continued. “I have suffered great psychological trauma, and I can’t imagine living with any man. I’ve also been greatly impacted and shocked by the contradictions present in our society. While many people stress the importance of caring for the faultless victims of sexual assault or rape, they act in a way opposite to what they preach. Because of this, I feel a great deal of frustration and despair that sometimes makes me wish I would die.”

Various documentation centers’ statistics reflecting society’s abuse of Syrian women who were stripped, assaulted or raped in prison are still vague and incomplete. However, the rape of women by government forces and militias continues and is getting uglier and more malicious. And while many victims of rape have spoken out, the international community and international courts are not taking appropriate action to support these women.

......