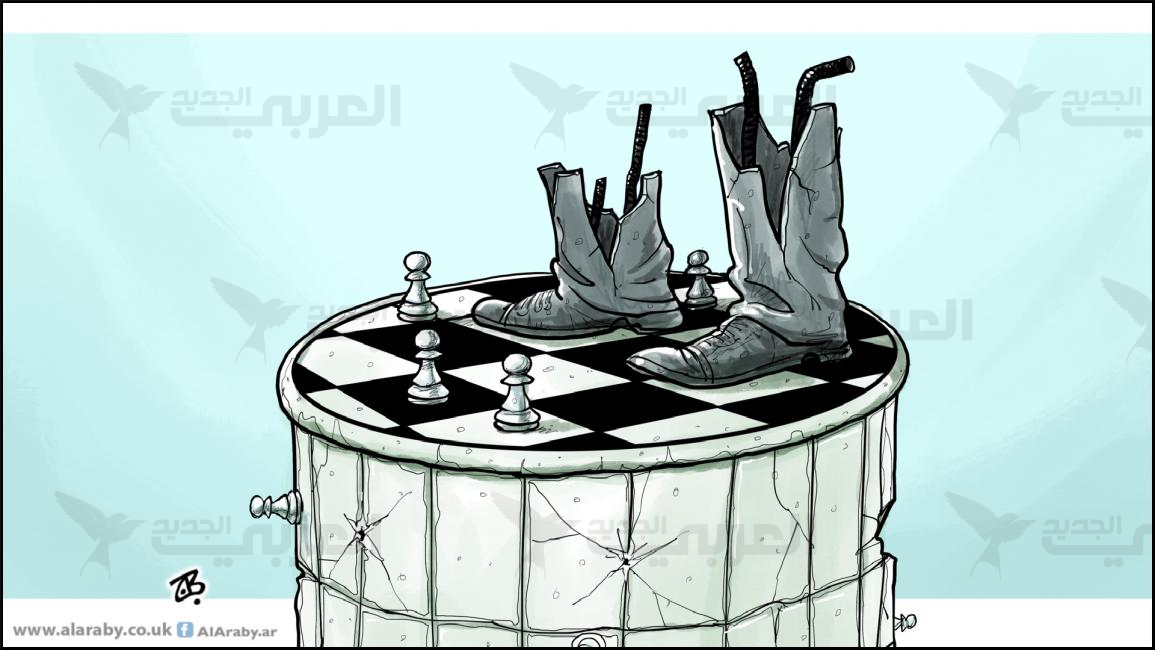

Observers of Syrian affairs have noted a growing chorus of concerns regarding the country’s future, which can be broadly categorized into three key fears. The first is the fear of a resurgence of internal armed conflict, fueled by various pretexts and motives, most of which reflect ongoing international and regional rivalries over Syria. This includes the persistently destructive interference of actors like the UAE regime. The second fear centers on the potential domination of Hay’at Tahrir al-Sham (HTS) over the Syrian landscape, culminating in the establishment of a new authoritarian regime reminiscent of the Assad regime or akin to the current governance model of HTS in northern Syria, bolstered by regional and international support. The third is the fear of a replication of the Egyptian model under Abdel Fattah al-Sisi, where protests against the current de facto government could lead to infiltration by remnants of the former regime, ultimately resulting in a coup and the re-establishment of the old regime’s structures and influence.

Acknowledging Legitimate Concerns

These fears are not without merit. Each has its own context, causes, and contemporary examples. However, it is essential to highlight the resilience of the Syrian people—a resilience that has prevented the complete defeat of the Syrian revolution (though it is premature to speak of its victory). This steadfastness endured despite the brutality of Assad’s regime, supported by his allies and, at times, exacerbated by some opposition factions. Without this resilience, efforts to rehabilitate Assad’s regime would likely have succeeded. It is this enduring strength that forms the foundation for the Syrians’ ability to thwart counter-revolutionary attempts and eventually realize their revolution in its fullest sense.

Foreign Interference: A Persistent Threat

The fear of continued or renewed foreign interference—whether from the UAE, the U.S., Iran, Russia, or Turkey—remains valid. Foreign meddling in Syria has been unrelenting, manifesting in various forms: sustained Israeli occupation of Syrian territories with at least tacit U.S. support, the ongoing presence of American forces in northern Syria, Turkey’s military approach to the Kurdish issue, and the activity of pro-Assad factions, reportedly supported at times by the UAE and Iran.

The writer argues that the Syrian people’s silence regarding the overreach of the current de facto government has neither shielded Syria from foreign interference nor curbed it. On the contrary, this silence, coupled with HTS’s internal preoccupations, appears to embolden external actors. HTS, burdened with managing internal control—spanning economic, political, cultural, and security issues—has yet to establish comprehensive security dominance in northern Syria. Past reliance on military and security solutions alone failed to achieve this, and there is little reason to believe such tools would succeed now.

The absence of media and public oversight in so-called security matters poses grave risks, opening the door to two dangerous trends that could destabilize Syria. First, unchecked revenge-driven actions could escalate beyond targeting those culpable in Syrian bloodshed, encompassing minor, unproven, or even imagined offenses. Secondly, oreign powers could exploit security vulnerabilities through bribery, sowing divisions, disseminating propaganda, incitement, and sectarian or tribal provocations.

Addressing HTS Domination Concerns

The legitimate fear of HTS consolidating an authoritarian regime requires Syrians to reclaim their oversight and political roles. The early days of the Syrian revolution demonstrated the potential for grassroots political and social organization. Renewing and accelerating these efforts is imperative before external intervention deepens and before HTS can entrench strict security measures that lay the groundwork for authoritarianism.

While the fear of an Egyptian-style counter-revolution under Sisi remains widespread, the writer considers it less likely. Key structural differences between the Syrian and Egyptian contexts make a similar outcome improbable. Bashar al-Assad’s fall represented the complete collapse of his regime, unlike Egypt’s transition, which was mediated by a deep state. Syria lacks such a deep state; Assad’s regime functioned as an overtly exposed and centralized cabal, leaving no institutional buffer to perpetuate its power.

However, preventing the resurgence of the old regime requires proactive Syrian involvement. The return of former regime elements would necessitate the complicity of the current de facto government. Therefore, holding HTS accountable and preventing such collusion demands organized and conscious political engagement from the Syrian people.

In conclusion, while fears of a counter-revolution are legitimate, the ultimate guarantee of Syria’s freedom and progress lies in the active participation of its people. Only through their vigilance and effectiveness can the country chart a path toward genuine independence and development.

This article was translated and edited by The Syrian Observer. The Syrian Observer has not verified the content of this story. Responsibility for the information and views set out in this article lies entirely with the author.