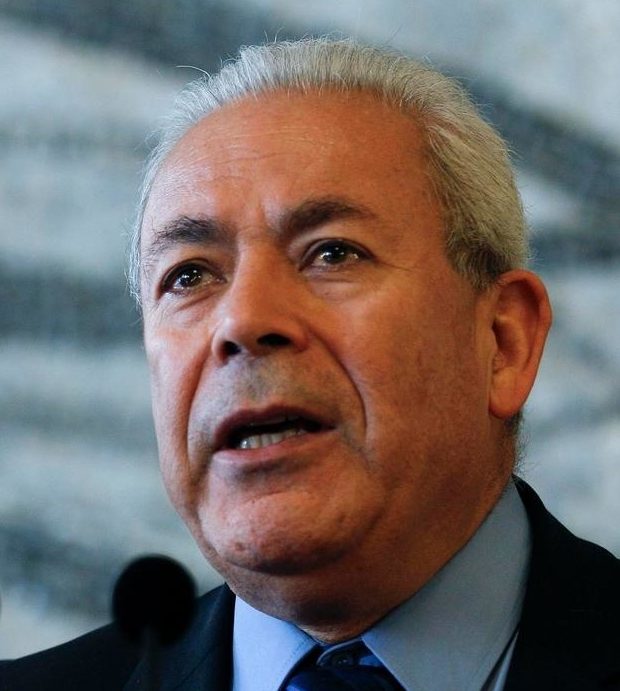

In this interview with The Syrian Observer, Burhan Ghalioun offers a perspective from the Syrian opposition on the conflict engulfing the country since 2011.

Dr. Ghalioun is an academic and a Professor of Sociopolitical Science and Director of the Center for Contemporary Orient Studies at the Sorbonne University in Paris since 1990. He is a longtime member of the Syrian opposition from well before the onset of the uprising and was the first Chairman of the Syrian National Council in August 2011.

This interview is the fourth and last of our series of interviews we are conducting on the 10th anniversary of the Syrian uprising. You can read the first three interviews we conducted with historian Nadine Meouchy, French diplomat Michel Duclos, and political scientist Steven Heydemann.

When the Syrian uprising began in 2011 Bashar had been in power for 11 years and some still held hope that he would bring reforms. Did you still have any illusions?

When he acceded to power, I did think that if Bashar did not want to be just a mere heir to his father and wanted other forms of legitimization, he would seek to open up. However, I soon enough discovered that he was too weak to do so, for several reasons.

First, he became president based on a decision from the entrenched networks that formed during his father’s era. Those who put him in power did so to protect their interests. They did not bring him to power because of his talents or political and military acumen.

Secondly, any serious change requires a minimum level of political courage and experience, and a minimum of moral influence over the ruling elite, including the leaders of the security apparatus and officials in the higher echelons of the state. Bashar lacks all these qualities.

Third, he did not have his own team to help him confront the veteran military, security, and Baathist leaders. When he tried to benefit from Syrian expatriate experts, such as Issam Al-Zaim and Ghassan Al-Rifai, he could not protect them from those with real power who wanted Bashar to remain completely in their grip.

When Bashar was forming his first cabinet, his wife’s uncle came to me and offered me a portfolio. He said that Bashar was young and had studied in Europe and that he was betting on people like me to help him achieve reform. My answer was that youth and residence in the West do not necessarily make someone a political leader. Even if he had a truly reformist will, something that needed to be tested, what could he do to dismantle the networks and mafias that control the system? I explained that the system was stronger than the individual and that Bashar was condemned to remain hostage to the will of these people or else he would be sidelined.

Thus, I never took a bet on the myth of Bashar being a young president and being married to a westernized woman. On the contrary, I foresaw his weakness and helplessness towards powerful regime figures and, later after the revolution broke out, towards Iran and Russia. He is ready to ally himself with any devil that would save him and use his position to gain more wealth for himself and his family.

Was the Syrian opposition ready at the outbreak of the Syrian uprising? Do you think that political activity in the 2000s (Damascus Spring in 2000-2001, Damascus Declaration in 2005, joint Syrian Lebanese activity) was a prelude to the Syrian revolution?

It is an exaggeration to talk about opposition in Assad’s Syria. There were opposition figures, but there were no opposition institutions. The state of emergency and the multiple security services aimed solely to kill these opposition institutions in their infancy. This explains why most of its members were for decades either in prison or in exile. They had no possibility to be active and communicate with the public. There were few brave individuals trying to seize opportunities from time to time to express their views and criticize the regime’s policies.

In 2011, the opposition was unable to realize that what was really going on was indeed a revolution. This explains why, seven months after the start of the revolution, it was unable to reach an agreement despite calls to do so by the young activists on the ground who had been overtaken by the events, and who faced severe repression from the regime. This also explains why many other attempts failed. The Syrian National Council, established in 2011, was initiated by Local Coordination Committees on the ground, not formal opposition groups. The current Syrian National Coalition came at the initiative of the Friends of the Syrian People Group. Today, after ten years, there is no opposition to speak of.

However, the political and intellectual movement known as the Damascus Spring played a role in the events of 2011, through the new concepts it introduced and the example it gave of gathering and protesting. It helped generate a new culture that inspired the youth of the revolution. Eventually, regime repression succeeded in dispersing and eliminating activists. The door was then open for forces that were marginal during the Damascus Spring to rise and dominate the scenery with a mixture of religious, tribal, regional, and sectarian culture.

Do you consider anyone standing against the regime as being part of the opposition? What position should the opposition take regarding radical Islamic organizations, including ISIS, HTS, and all other Islamist groups?

The common idea is that everyone who stands against an existing regime and seeks to change it or its policy, in any direction, is called opposition. There is an Islamic, secular, and extremist opposition, and perhaps sectarian, tribal, nationalist, and racist opposition. We cannot just claim that any party that does not share our views is not part of the opposition and refuse to recognize them. There is no reason for all the opposition parties to be in the same boat.

Political alliances are usually established between different forces based on a political project. This project, which the revolutionary forces fought for, is to overthrow the despotic regime and establish a democratic system that guarantees freedoms and equal rights for all Syrians without discrimination. This is the essence of the demands of the population. Anyone who approves of this program can be incorporated into the bloc of the democratic opposition, and whoever rejects it cannot be part of the bloc. Jihadist and Salafi currents chose to work on their own and confront democratic forces and the regime at the same time.

In a recent book, you talk at length about the Muslim Brotherhood. Is it possible to ally with them within the Syrian opposition?

The Muslim Brotherhood in Syria is an organization born during the era of liberal governments, and its first guide, Mustafa Al-Siba’i, adopted a democratic position and concluded political agreements with left-wing parties in some parliamentary elections in the 1950s. During the Damascus Spring, the organization confirmed its affiliation with the democratic movement and the civil state and became a member of the Damascus Declaration bloc. In the same line, they joined the Syrian National Council in October 2011. However, after the decline of democratic forces during the revolution and the rise of the Salafi and jihadist trends, the Muslim Brotherhood implemented a different agenda that flirted with Salafi trends.

Is it possible to ally with the Brotherhood within the framework of a democratic front? That depends on which alliance you aim for. If the future for Syria is a democratic system, it is likely that there will be competition between moderate Islamists and democrats, and there will be no room for discussion of an alliance. I think that falling into the arms of the Salafists is not in the interest of the Brotherhood and contradicts the essence of their political belief. In my book titled Criticism of Politics: The State and Religion, I had called on them to shift to an Islamic democracy along the lines of Christian democracy that was known in most European countries after World War II.

How do you view tensions between Arabs and Kurds? The Democratic Union Party (PYD) seems to have shifted slightly its position, ruling out secession and even federalism, and adopting the concept of expanded decentralization. Is it time to integrate it within a unified Syrian opposition?

It is imperative to open an in-depth dialogue with all Syrian Kurdish political forces, as there should be no barriers to working together on a democratic project. In previous years, some Kurdish forces shifted away from a unified democratic project and worked on different national and party agendas, which created differences with other democratic forces. There is a range of issues that need to be agreed upon by all Syrians, through democratic solutions. Among these issues are the military, the Autonomous Administration system, extending the Kurds’ power politically and geographically to the east of the Euphrates, etc. Syrians must come together to agree on a common vision for Kurdish national rights within the framework of the Syrian Republic.

Did the constitutional committee reach a dead end? The Kurds and Hay’at Tahrir al-Sham are the only forces that oppose the regime on the ground now, yet they are not represented in it.

The Constitutional Committee did not reach a dead end. It is doing exactly what it was supposed to do: block the Geneva process and create a Russian-Iranian-Turkish bloc that strengthens Moscow’s position in the face of the Western bloc. Hence, it has succeeded in its mission completely. Political negotiations have not made any bit of progress in ten years. The solution is not to introduce Kurdish parties to the Committee, but to return to serious negotiations that respect the UNSC resolutions, including Resolution 2254, and begin to form a transitional governing body that works according to a temporary constitutional document to prepare for democratic elections, under the supervision of the United Nations. These elections will create a representative, inclusive government, with sufficient power to solve the main structural problems. This will cover governance and decentralization or even autonomous regions – if there are legitimate demands for that. Without this, a legitimate authority that is trusted and capable of rebuilding the Syrian state will not be formed. Instead, division, dispersion, and tension among the various actors on the ground will remain. We will never get out of the civil war and. Instead of having a democratic, pluralistic state, we will enter the maze of multiple civil wars and without a state.

Is the time ripe for the emergence of a new opposition formation that would transcend divisions and mistakes from the past or do you think that Syrians have just proven unqualified to work collectively?

Unfortunately, we are getting increasingly dispersed, and we still accumulate mistakes. However, this has nothing to do with the Syrians’ eligibility, for Syrians are not a human species different from other societies. Rather, this is the price of frustration resulting from the losses we suffered, the sacrifices we made, and the absence of hope. It is also the price of the exceptional violence inflicted on our people which was left facing a regime using violence, intimidation, and terror. It is also the price of the international community’s abandonment of the Syrians in their dire ordeal. Syrians need hope and want a dignified life. An important step to do so would be for major democracies to form a special tribunal to look into war crimes in Syria.

The conflict in Syria has been largely internationalized. Is there any role left for the Syrian political actors?

Internationalization has fragmented the country, consolidated sectarian, ethnic, and regional divisions, and normalized proxy wars. I do not think that it will be possible to solve the conflict without the involvement of Syrians and more than ever they need to take their fate into their own hands as much as possible.

Burhan Ghalioun was interviewed by Wael Sawah. This article does not necessarily reflect the opinion of The Syrian Observer.