“All of us, Alawites, Sunnis and every kind of Syrian will topple this regime, we don’t want any of its members to stay in Syria, and I speak for all the Alawites of Syria.” A young man said these words with a rural Alawite accent as he was filming part of a demonstration on March 15th, 2011 in the Al-Hamidiyah area of Damascus. It was clear to anyone who knows the rural Alawite accent that this wasn’t his real accent, he was only trying to say that not all Alawites support the Assad regime. Later, on the same day, in a phone call with Al-Jazeera, a Syrian activist said, “the Syrian revolution has been launched, and it will not stop until this regime is toppled. And I tell my Alawite brothers: don’t be afraid, you won’t be harmed.”

This clearly indicates that prior to the revolution, there was a certainty among Alawites that they believed they would be in danger if the regime was toppled; thus they would not support the revolution unless they were given enough assurances, so something should be done to solve this problem. In parallel to this idea, another one slowly appeared during the early months of the revolution — that the regime was an Alawite regime, or a regime for Alawites, implying that the fate of Alawites was linked to the fate of the Assad regime.

Anyway, the course of events proved this belief, as areas with an Alawite majority, either in the country or in the cities and their slums, became obstacles in the way of the revolution’s progress and expansion, both at peaceful demonstrations and the level of armed action. As the conflict continued and turned more bloody and complicated, most Alawites kept up their support for the regime, which continued destroying rebellious cities and villages and forcing people to migrate. Thus, the vengeful discourse that called for punishments and revenge against Alawites became stronger than calls for collaboration with them to topple the regime. This coincided with another discourse, that of the Salafi jihadists, which considered Alawites to be apostates who should be fought, regardless of their political positions.

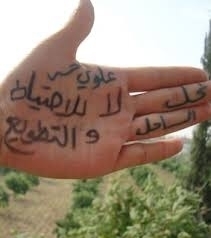

During the revolution, many voices arose saying that Alawites were growing furious and heated, and that Alawites would soon revolt against the regime. Many groups and pages were created on social networks that discussed Alawites starting a movement against the regime. But these actions stopped and lost its credibility as the conflict grew larger and the sectarian alignment grew wider. More recently, as the number of Alawite victims has grown, the movement reappeared, with some photos published on Facebook showing a small number of people along the Syrian coast holding signs that expressed their anger toward the Assad regime. This was enough to set off a fabricated fanfare about Alawites complaining about the Assad family, and about how they would soon abandon the regime. Many articles described the depth of this movement, and how it was lacking funds, connections, and media coverage, and about how it was deliberately ignored by opposition organizations. Those articles also spoke about a confusion within the security agencies who had allegedly raised their alert levels as a reaction to this movement, which was called “The Cry.”

This type of media work was common in the early stages of the revolution, but the course of events proved it was useless, even long before extremism and sectarian alignments began. In spite of the rage and anger that started to spread among Alawites, we still can’t expect any results from this kind of work. This, regardless of what will be discussed later, is a result of what Alawites witness today as the Islamic groups take over large parts of Syria. It is also a result of the existence and progression of the Islamic State, which threatens their lives.

History’s Heavy Legacy

All explanations that are based on identities or sects, which invoke ancient grudges and ideological differences between Sunnis and Alawites, offer us no valuable analyses as to why most Alawites support the Assad regime. They usually end up explaining that Alawites are Alawites and nothing more. Explanations that hide the truth, or say that sectarianism is “made by the regime” or any other group, don’t explain a thing — tens of thousands of Alawites face death daily on the battlefronts, supported by their social environment and families. This issue needs to be explained far away from typical grudges and illusions.

A heavy historical legacy reigns over everybody. Prior to the establishment of the Syrian state, Alawites lived as subjects of the Ottoman Empire for roughly 400 years (1516-1918), and they were exposed to various kinds of oppression for centuries. The Ottoman Empire, like all other empires, oppressed all of its subjects — but Alawites were oppressed on a sectarian and identity basis, and the impact is still present in their memory to this day.

In Alawites’ memory, the truth about their relationship with Sunnis is mixed-up with myths — and perhaps myth has more influence than truth in human memory, especially when it is invested in by the authorities to fulfill their projects. Nevertheless, there was no clear or legal regulation regarding the relationship between Alawites and the Ottoman Empire, yet the historical references indicate they lived in poverty, ignorance, and isolation on mountains far from the cities. They were connected to the empire’s capital in Istanbul through groups of influential lords, who in some cases were Alawites close to the imperial governors. Additionally, there are many fatwas that permitted the killing of Alawites for being apostates and libertines (perhaps Ibn Taymiyyah’s fatwa on “Alawites” is the most famous one). These fatwas are mixed with stories about decapitations, killing children, raping women, and impaling men — stories that are found in all wars and conflicts around the world.

There were two solutions to get this heritage of historical oppression out of Alawites’ heads; either establish their own political entity or establish a national state where they would be considered citizens. Unfortunately, neither of these solutions was applied. Instead, during the French mandate, Syrian elites (including Alawite elites) refused to establish an Alawite state, and chose to establish a centralized Syrian state within the borders set by the nations who emerged victorious from World War One. This state has never been a state of true citizenship, not even for a single day.

All the “national” governments that were formed during the mandate (1925 to 1947) and after independence in 1947 failed to build a progressive national project. Successive generations of Alawites retained this heritage for years, as they moved from the country and the mountains toward cities, and toward education and government jobs. They depended on the state and its emerging national institutions, which faced many obstacles, including the most difficult, the declaration of the union with Egypt in 1958.

Later, when the Ba’ath party seized power in 1963, Alawites began entering state agencies and living in the cities protected by military and security agencies, which began to multiply and grow more brutal on account of other state institutions. The idea of a national state — which wasn’t yet mature — was abandoned, and replaced by the idea of the revolutionary Ba’athist legal power, which resituated Alawites alongside all other Syrians in the context of its totalitarian authoritarian project.

The state’s power was the reason why Alawites moved from the countryside to the city, and from farming and grazing into universities and industrial, commercial, and government jobs. This is the common story among Alawites; they also believe that Sunnis are waiting for the perfect chance to kick them out of the state [bureaucracy], its institutions, and cities, and [send them] back to the mountains. Discussing the validity of this story isn’t important, but what is very important is noting that this story has helped the Assad regime to situate all Alawites where it wanted them, since there were no alternative narratives to allow Alawites to get rid of this legacy.

At the same time, in the era of the Assad regime, some Alawites were given unprecedented power; Alawite officers in the army and security agencies started acting as the real power holders. The massacres of Hama in February 1982 influenced Syrian memory in general, and especially Alawite memory; all Alawites knew about the massacre, and knew that an Alawite president, Hafez Al-Assad, was responsibile for these massacres against Sunnis. But the authorities justified these actions as a reaction to the deeds of the Islamic brotherhood’s “fighting vanguards,” which represented, to them, the threat of a return to oppression and being excluded from the state agencies and cities.

Later on, all civil and left wing movements were disbanded and hundreds of opposition figures, including Alawites, were imprisoned. The authority of the sectarian security agencies and the army, which had allied with businessmen and industrialists of all sects, started to weaken the authority of the state institutions, which were backed by religious authority in the eyes of all sects, especially Alawites, whose clergymen have fully integrated into security agencies in the past 10 years. All of this happened during a period of unprecedented corruption, bad education, eschewing dealing with general issues, and an economic collapse prior to the Syrian revolution.

The Context of the Syrian Revolution

As the revolution was beginning in 2011, a constellation of four factors helped provide unconditional support, transforming ssad’s authority into the authority of a state that protects all Alawites. These four factors were the insistence that Alawite elites in the security and military maintain their control over power and money, as they always did; Alawite fears of a return to oppression, exclusion, or even being killed; and the anti-ideological Islamic discourse among the rebels that started spreading along with other ideologies invoked throughout the stages of the revolution.

The fourth factor is the economy. Only a few influential Alawites were sacking the resources of the country, while tens of thousands of junior military and security officers and government employees lived on pensions from the state treasury, benefiting from the corruption of the public sector in Syria. There are no accurate statistics about this issue, as with all other issues during the era of Assad’s totalitarian regime, but surely at least half of all Alawites live on the state treasury. If we count those who work in the private sector but whose work is connected to the work of the public institutions, and those who benefit from their relationship with government employees, then the percentage of those who live off the state treasury becomes more than half.

Many related factors constituted an unbreakable, solid core of support for the Syrian state’s authority. There were the fears that accompany all revolutions, fears of chaos, and of the absence of state authority, which are common denominators among middle class people in any society. In Syria, all of the above were accompanied by chaos, the absence of [oppositional] organization, and the absence of any discourse that supported the establishment of a new state by the Syrian opposition. Moreover, there was a disabling of the educated Syrian elite — they were mostly captivated by proposals that were uncertain about democracy, freedom, and equality, and by the project of [establishing] a national Syrian state that has never been seriously evaluated.

This is the situation of Alawites today: fear of oppression, economic connection to the state treasury, the absence of any elites offering a new and useful discourse, an opposition and a revolution that have no proper tools or conditions to attract Alawites and change their decision, and a fascist, factional regime that implicated Alawite children in dozens of sectarian massacres. Above all, there is the discourse of Alawite elites in the military, religious [institutions], and the economy, which are ultimately connected to the regime and its discourse, and totally captivated by the state and the necessity to protect it at any cost. This equation seems to have no solution; on one hand the price is too high, with statistics citing over 100,000 deaths, while on the other hand their lives are being threatened by several groups, including IS.

The Cries of Alawites Today

What cry could Alawites yell out today? And which Alawites are we talking about?

We won’t discuss the issue of the Alawites in the opposition, or the middle class educated Alawites who support the regime, ot those who haven’t stopped defending its secularism and progressivism. We won’t even discuss those who benefit from the corruption of the regime and the dominance of its military and security agencies, since they are a part of the regime, and perhaps its main core.

We will talk about common Alawites, who live in the country and the slums around the cities, who have paid and are still paying the price of this war, and who have the right to scream at the world, including at Assad regime, and say “Why are our children dying like this?” Everyone who talks about Alawite restlessness and revolution bets on this class, but this bet seems to have no credibility among those who are supposed to be the bet. It began with rumors of cleavage, disorder and confrontations in Qardaha and other places throughout the different stages of the revolution, then came the tragic Alawite opposition conferences, and finally propaganda that bears no real results on the ground.

This class knows that Assad will remain in power while their children will be in coffins, a truth they have to live with each day, without a single hope of salvation. Their cries have never reached the media and haven’t been represented by any political movement, and the worst thing is that no one understands them or knows what they want. In spite of all their anger with the situation under the rule of Assad junior, they still believe that their salvation depends on his regime. Dozens of their children are still fighting, while others, who don’t want to fight, have skipped military service without joining any new alignment or movement.

With all of this, it was easy at the beginning of the revolution to form sectarian militias formed mainly of Alawites — these militias, which are now called the National Defense Force, have committed many horrible massacres, exterminations, displacements, and organized robberies. Their crimes have become another heavy legacy that seems to have no solution. Behind a thick wall of blood, obscuring sight, the cries of Alawites are being strangled. They are mere mumbles that no one understands, as they watch their children die in the deserts, and for nothing.

Although they are convinced that there is no benefit for them, any break from the ruling junta in Damascus isn’t going to lead them to revolt against Assad. It would only cause them to fall back into place to protect the regime. This would only lead to undermining the Syrian nation, which is already decrepit.

......