Fears are growing for the tens of thousands of detainees languishing in Syrian regime prisons as the coronavirus spreads through the war-torn country, with poor conditions and a history of mistreatment exacerbating concerns.

Syria’s intelligence infrastructure currently holds around 130,000 detainees, according to the Syrian Network for Human Rights (SNHR), with most arrested since the beginning of the popular democratic uprising against Bashar al-Assad in March 2011.

At least 14,000 people are thought to have been tortured to death in regime jails, with mounting warnings that the spread of coronavirus could have devastating consequences for those currently imprisoned.

In response to the coronavirus, Syrian regime authorities have announced a partial curfew and closed educational institutions and government departments.

There are officially 39 confirmed cases of the virus and six deaths, although the regime is widely believed to be underreporting the true number of cases.

“We urge the authorities to cooperate with relevant humanitarian organisations wherever possible to plan and take the necessary precautions to prevent the spread of Covid-19 in prisons, and to ensure that prison conditions meet international standards,” Rosie Dyas, the spokesperson for the British Government in the Middle East and North Africa region (MENA), told The New Arab.

“The safety of detainees in Syrian prisons is the responsibility of the authorities responsible for those detention centres, and with the assistance of relevant humanitarian organisations, where possible, to support the efforts of the authorities to prevent the spread of Covid-19,” she added.

Prisoner conditions

A lack of water, food, and medical care are common torture methods employed in Syrian prisons and detention centres, a reality of which 33-year-old Bashir al-Abdo from Idlib province is all too aware, having spent eight continuous years in regime jails.

“Water is barely drinkable, and always scarce, so it cannot be used to clean places of detention, wash clothes, or even wash hands,” al-Abdo, who lives in Turkey, told The New Arab.

“I was held with two people in solitary confinement in an area of three meters. In the middle was a toilet whose water is cut off for one day and comes back the next”.

After 60 days, al-Abdo was transferred from Branch 291 to Branch 248, which is also run by military intelligence, where he was crammed into solitary confinement with five people without water or toilets.

“I could barely take a piece of bread with some rice or vegetables on it and eat it due severe beatings with sticks, and insults,” al-Abdo said, adding that the toilet was the only source of drinking water.

After 30 days of solitary confinement in military intelligence, al-Abdo was transferred to Sednaya prison near Damascus, a secret jail run by the intelligence services where large-scale executions were carried out, according to Amnesty International.

“We used to fill water in worn-out plastic bottles, because the water was sometimes cut off for four days. Some detainees die of thirst in solitary confinement,” he said.

Thousands detained

The Syrian regime’s intelligence services are divided into four areas; military intelligence, state security, political security, and air force intelligence. Its headquarters are in the capital, Damascus, and it has branches in all provinces and control points in cities and villages across the country.

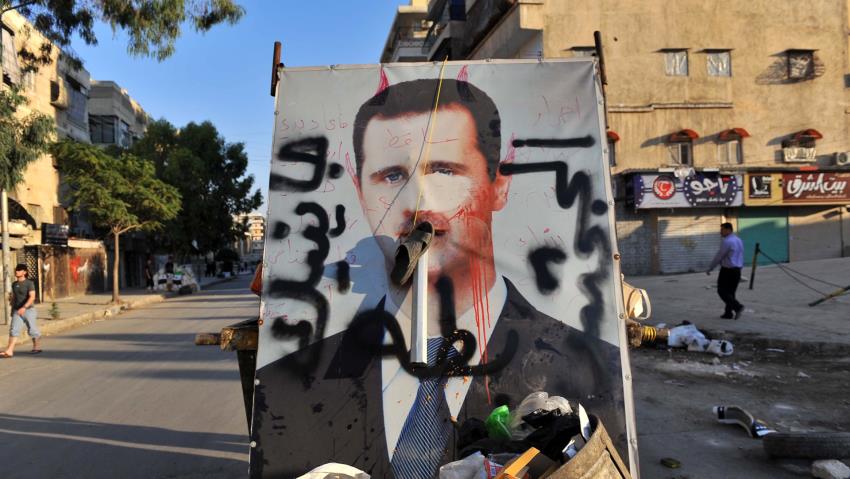

The four services actively pursue opposition activists inside and outside the country, and are linked with the National Security Bureau, which has been affiliated with the ruling party since 1963. Syrian President Bashar al-Assad directly oversees the management of the intelligence services, although each has an actual head.

Al-Abdo was arrested in 2011 months after the revolution, which later evolved into a brutal, and ongoing, war. He was studying at the University of Latakia province and working as an activist, capturing the scenes of protests. Under torture, he was forced to make false confessions to state media.

SNHR estimates that some 1.2 million people have been arrested in Syria since 2011. “Because of overcrowding, I felt that half of the country’s population was being held. Lucky are those who can sleep sitting,” al-Abdo said.

“Most detention centres are underground so the humidity was high, and the ventilation was always lacking, which causes shortness of breath,” he said

“[There were] bleeding wounds resulting from torture everywhere. It is impossible to maintain cleanliness due to the lack of water, if any new prisoner enters with any disease such as a cold, everyone will be infected,” he added.

Human rights groups have lamented the conditions for prisoners in Syria, urging authorities to take action to prevent the spread of Covid-19.

“In Syrian prisons and detention centres, COVID-19 could spread quickly due to poor sanitation, lack of access to clean water and severe overcrowding,” said Lynn Maalouf, Amnesty International’s Middle East Research Director.

US-based rights group Human Rights Watch (HRW) has also expressed concern that detainees are vulnerable to the spread of coronavirus.

“Syria’s prisons hold tens of thousands of detainees. Many have been arbitrarily detained for their participation in peaceful protests or for expressing dissenting political opinion,” the group said.

Lack of medical care

In Syrian jails, the lack of medical care is often a death sentence, with detainees scared to even ask for treatment for fear of reprisals and beatings.

“The vast majority die due to lack of medical care, diseases caused by lack of hygiene, nutrition, water, and weak body immunity,” Fadel Abdul Ghany Chairman and founder of SNHR told The New Arab.

Sometimes injured prisoners are treated in hospitals in Damascus run by intelligence services, namely Al-Mazzeh Military Hospital 601, Tishreen Military Hospital 607, and Harasta Military Hospital.

But only detainees whose wounds have become severely infected and may need amputation are treated, and they spend the entire duration of their treatment in handcuffs.

“We have been informed by some of the detainees that they have been subjected to severe torture in hospitals. The Syrian regime does not have the capacity to provide respirators or treat detainees if corona[virus] spreads among them,” Abdel Ghani said.

The scale of torture in Syrian regime military jails was illuminated in 2014 by a Syrian military defector known as Caesar, who leaked photos of some 7,000 dead detainees.

The photographed prisoners showed skeletal and mutilated corpses with burn marks, fractures and multiple wounds.

As a result, the US passed the Caesar Act last year, which will target Syrian regime officials involved in murder and torture. It is expected to take effect in June.

The US has confirmed that the sanctions will not affect the “delivery of food or humanitarian goods, including medicines and medical supplies” into Syria to help fight the coronavirus.

Access to jails

In light of the dire situation in Assad’s jails, HRW has called on humanitarian organizations and United Nations agencies to urgently press for access to formal and informal detention facilities to provide detainees with life-saving assistance.

Nour al-Khatib, the official responsible for prisoners in the SNHR, recommends that specialized international committees should enter detention facilities without conditions or pre-scheduled dates, in order to improve conditions and prepare detainees for their release.

“The inspection committees are an urgent first emergency step to relieve the torture of detainees and spare them the corona[virus] epidemic until a political solution begins,” she told The New Arab.

Despite the calls, arrests are continuing. According to SNHR, the intelligence services arrested 156 people in March, and at least 36 people so far in April.

“The regime’s non response does not mean that the pressure will stop, we will continue our demands until arbitrary arrests are stopped and all detainees are released,” Al-Khatib said.

The Syrian Observer has not verified the content of this story. Responsibility for the information and views set out in this article lies entirely with the author.