The dialectic of the Assad regime’s relationship with its loyal “slaves” in Syria often emerges amid complex circumstances. This relationship is marked by an emotional bond fraught with contradictions, as seen in the recent arrest of Bashar Barhoum, a prominent supporter of the regime. This incident underscores the difficulty in understanding the root causes of Syrian impoverishment and its current repercussions. After decades of Assad’s absolute rule, dismantling this pragmatic, intertwined, and reciprocal relationship is nearly impossible. It is a relationship that begins with historical injustice, shaped by the nature of the group itself, and extends to the existential threats posed by the 2011 revolution and subsequent civil war.

The plight of the Alawites is intricately tied to history’s cunning, which transformed them into a tool for the regime. The perception of their distinctiveness from other sects is rooted in sectarian fanaticism, as described by Ibn Khaldun, used to distribute power absurdly and coercively. This reality is imposed by the Assad regime, emerging from distorted cultural and political structures formed through a history of military coups and complex power dynamics.

This perspective is not pessimistic but rather objective and supported by historical evidence. Assad the father did not aim to build “political Alawism” in the literal sense but was drawn into it. His objective was to transform his rule into a permanent hereditary authority, preventing any transfer of power. Since the 1970s, he diligently worked to detach the oppressed sect from its social context, transforming it into an outcast agent class without clear historical roots, a strategy continued by his son. The more complex this partnership becomes, the more its manifestations differ based on the conditions governing it. Recognizing this may be the key to understanding the relationship. However, assuming that Assad seeks refuge with the Alawites and is shaded by their fears only strengthens their attachment to him, dealing with the idea of overthrowing Assad as a direct threat to their existence. This sentiment persists despite widespread resentment within the Alawite community against a regime that has driven them to despair.

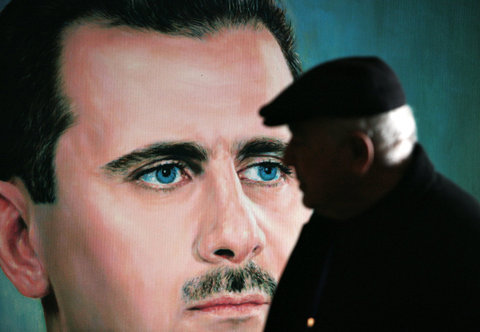

The Assad regime excels in exploiting its sect and manipulating their existential fears, reminiscent of Frederick the Great of Prussia’s view of humans as a herd of deer in the nobles’ garden. This reveals Assad’s disdain for his supporters, viewing them as potential enemies, and not tolerating any deviation from the prescribed narrative. The irony is that Assad’s contempt for his loyal base parallels their determination to protect his throne. As political science professor Hilal Khashan in Beirut asserts, “The Alawites are crucial to Assad’s survival, and he cannot live a single day without their full support.” This raises questions about the state of the sect today amid the country’s crises and the regime’s clear political failures. Criticizing the government while relying on Assad’s “mercifulness” to hold it accountable reflects a contradictory exaggeration aligned with the regime’s deep-seated policies, turning its propagandists into “incense burner carriers” who only preach Assad’s divinity and eternal rule.

Sociological analysis helps us understand the Assad regime’s formation of its rural authority among the Alawites. As Frederick Engels noted, the farmer views his village as the entire world, so the marginalized sect saw the Assad regime as their salvation. The abrupt transition from Ottoman persecution to absolute privileges under Assad, without intermediate stages reflecting their evolving circumstances, explains their inability to form a cohesive political entity on a viable social base, even after Assad’s potential removal. Consequently, the Alawites struggle to simply turn against him, despite many taking explicit positions against the regime. Meanwhile, the regime continues to embrace its henchmen, who hope to gain from their loyalty or fear repercussions, alongside relatives integrated into powerful government institutions and then suddenly liquidated or gradually excluded. Just as Assad the father assassinated his sister’s son, Dr. Ibrahim Naama, for supporting Mahmoud Al-Zoubi against him in party elections, Assad the son did not hesitate to remove his cousin from the throne of the Syrian economy for refusing to pay war debts to allies, according to The Times.

On the other hand, others were granted secret privileges on the condition that they remained as “tame” opposition figures to decorate the façade of the Assad regime. This implicit alliance established a political interiority that spread to include a significant number of prominent intellectuals. This brings us to the phenomenon of “sectarian trumpets blaring,” characterized by linguistic exaggerations and blatant flattery. These are the Alawite drummers and pipers who excessively praised Assad, creating a sarcastic irony in the Syrian street. They became notorious for this characteristic, like Bashar Barhoum, who sought personal gains through blatant hypocrisy, showing no concern for the public interest. He freely expanded within a sectarian space charged with political burdens, demonstrating his loyalty to the regime. His arrest was not due to insulting his benefactor but for declaring explicit hostility to Iran. This scenario was repeated with pro-media personality Lama Abbas, who danced, ululated, and chanted at events glorifying Assad, only to turn against him later and be arrested after accusing Assad’s allies of crushing and starving the Syrian people and the regime of plundering the country and obliterating Syrian identity.

The propagandists of the Assad regime did not defend it from a standpoint of political realism. They were acutely aware that coexistence with the regime was a self-defeating opportunism, which only increased the likelihood of an inevitable rebellion. As the regime created a failed and chaotic state riddled with chronic violence, its propagandists began to turn against it one by one. Assad, in turn, did not hesitate to devour them at the political table as a cold and delicious meal.

Assad’s preying on the flesh of his “rebel” agitators is a pivotal event, revealing an explicit weakness that hastens his downfall. The moment of awareness of injustice is crucial and will push the sect to revolt against its executioner. However, achieving this soon is difficult because Assad has rendered the Alawites’ already troubled memory short and selective. They arbitrarily jump from being semi-serfs living the nightmare of Ottoman terror to embracing a brutal rule that transformed them into a working class without roots but with exceptional societal characteristics. Assad played the most cunning security and propaganda games against them while they believed there was never a period of “pride” in their history before Assad. This belief contributed to the sect’s rise in a way that made separating their ties a particularly complex and challenging task.

This article was translated and edited by The Syrian Observer. The Syrian Observer has not verified the content of this story. Responsibility for the information and views set out in this article lies entirely with the author.