The fall of the Assad regime has opened the door for Syria’s long-awaited transition from an authoritarian dictatorship—one that ruled for over half a century—to a system built on democracy, pluralism, citizenship, and the protection of freedoms. This is precisely what the Syrian revolution, which began in March 2011, aspired to achieve. However, history has shown that transitional periods are fragile and fraught with dangers, with outcomes ranging from successful democratization to the collapse of revolutionary gains and a return to authoritarian rule.

The experiences of Egypt and Tunisia, which underwent similar transitions during the Arab Spring, offer important lessons for Syria. Each case had its own unique circumstances, but they also share common patterns that Syria must carefully examine to avoid repeating the mistakes that led to counter-revolutions in those countries.

- Egypt: The Perils of Political Exclusion and Military Domination

In Egypt, mass protests forced President Hosni Mubarak to step down within 18 days, largely because the Egyptian military refused to suppress demonstrators. However, the military remained the real power broker during the transitional period. While the Muslim Brotherhood won elections and took control of parliament and the presidency, it failed to assert control over the deep state, especially the military, judiciary, and security services.

The Brotherhood’s political miscalculations—such as their attempts to dominate state institutions and their reluctance to form inclusive coalitions—played into the hands of the military. Amid rising economic crises and growing public discontent, Abdel Fattah al-Sisi led a military coup in 2013, overthrowing President Mohamed Morsi and establishing a harsher authoritarian rule than during the Mubarak era. The failure to consolidate democratic governance paved the way for a successful counter-revolution, reversing the gains of the Egyptian uprising.

- Tunisia: A Slow-Motion Counter-Revolution

In Tunisia, protests escalated quickly, forcing President Zine El Abidine Ben Ali to flee within a month. Unlike in Egypt, the Tunisian military remained largely neutral, allowing a civilian-led transitional process to unfold. Over the next three years, the country drafted a new constitution, held democratic elections, and witnessed a peaceful transfer of power.

Despite these promising beginnings, Tunisia’s democratic experiment faced major setbacks. In 2014, the newly formed Nidaa Tounes party, led by Beji Caid Essebsi, won the elections. Essebsi, a figure from the Ben Ali era, gradually empowered elements of the old regime, weakening democratic institutions. This culminated in the rise of Kais Saied in 2019, who dismantled Tunisia’s democratic system, centralizing power in his hands.

Although Tunisia avoided the kind of violent repression seen in Egypt, it ultimately succumbed to a counter-revolution—this time, not through military intervention but through gradual erosion of democratic governance by remnants of the old system.

- Syria: A Revolution Delayed, But Not Defeated

Syria’s revolution began peacefully in 2011, quickly spreading across the country. However, the regime’s brutal repression—including mass killings, torture, chemical weapons attacks, and large-scale destruction—forced the uprising into a militarized conflict. Unlike Egypt and Tunisia, the Assad regime was able to cling to power for over a decade, thanks to the cohesion of its security apparatus and the decisive support of Russia, Iran, and Hezbollah.

Yet, the economic collapse of Syria, increasing regime corruption, and shifting international dynamics eventually led to the downfall of Assad. In November 2024, the Operation Deterrence of Aggression—led by armed opposition factions, including Hay’at Tahrir al-Sham (HTS)—accelerated the regime’s disintegration. Within 11 days, Bashar al-Assad fled Syria on December 8, 2024, marking the end of one of the most oppressive dictatorships in modern Arab history.

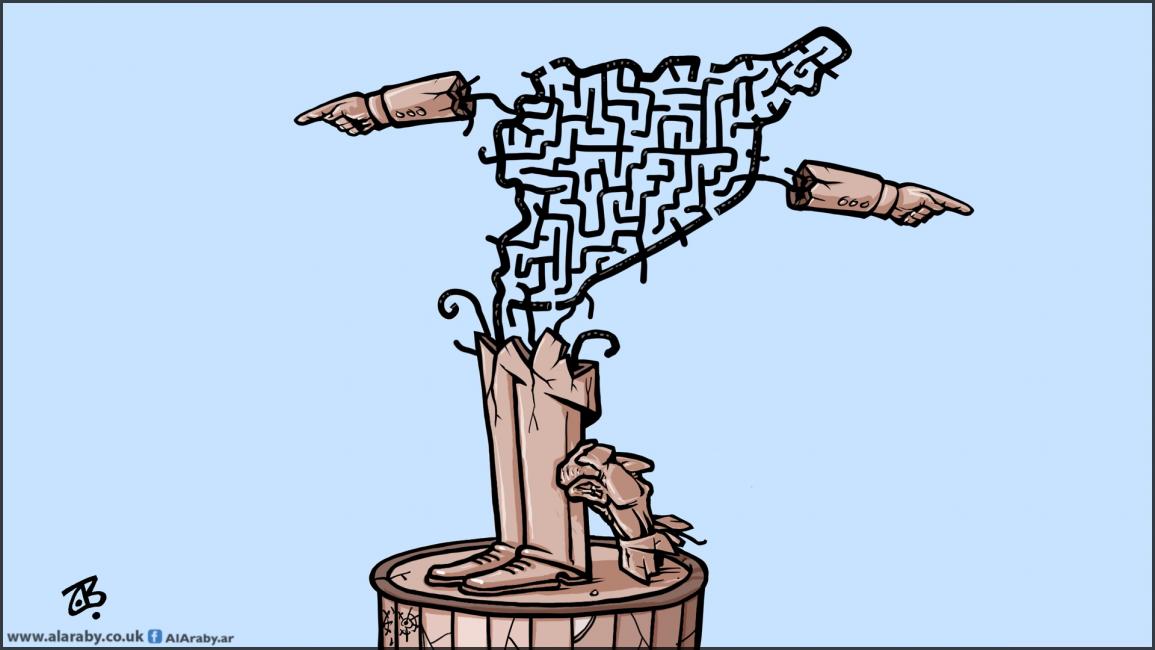

However, the collapse of an authoritarian regime does not guarantee a successful democratic transition. The real challenge now lies ahead: How can Syria avoid the mistakes that led to counter-revolutions in Egypt and Tunisia?

- The Dangers Facing Syria’s Transition

The Risk of Political Exclusion

One of the key lessons from Egypt’s failure was the absence of political inclusivity. In Syria today, the transitional administration is heavily focused on foreign diplomacy, while neglecting internal political dialogue. Instead of building national consensus, the new leadership is making unilateral decisions without broad consultation with Syrian political, social, and intellectual groups.

This lack of inclusivity is reflected in:

- Rushed economic policies without consulting experts or considering public welfare.

- The abrupt closure of public sector institutions and the mass firing of employees, creating economic distress.

- The absence of a national dialogue framework to ensure broad-based participation in governance.

This approach alienates key segments of society and risks fueling opposition to the new government, providing fertile ground for counter-revolutionary forces both inside and outside Syria.

Both Egypt and Tunisia failed to hold members of their former regimes accountable, allowing elements of the old deep state to regroup and eventually reclaim power. Syria faces a similar risk if it fails to properly dismantle Assad’s remaining networks.

Although the Syrian military and security apparatus have largely collapsed, some former regime figures still retain influence. There has been little focus on prosecuting key figures from the Assad regime, and in some cases, deals have been struck with known war criminals. If transitional justice is not prioritized, it will undermine trust in the new administration and leave the door open for counter-revolutionary actors to regain power.

To prevent this, Syria must:

- Immediately establish a Transitional Justice Commission composed of legal experts, human rights advocates, and representatives of victims’ families.

- Ensure accountability for crimes committed by the Assad regime, rather than seeking political compromises that allow criminals to walk free.

- Prevent revenge-driven violence while enforcing the rule of law to maintain stability.

Another lesson from Egypt and Tunisia is that political disengagement allows authoritarian tendencies to resurface. In both countries, early democratic gains were eroded as civil society weakened, allowing anti-democratic forces to consolidate power.

To avoid this fate, Syrians must remain actively engaged in shaping their country’s future. Civil society organizations should:

- Hold the transitional government accountable and resist any signs of authoritarian consolidation.

- Encourage broad political participation beyond just the factions that fought against Assad.

- Promote a culture of democracy and inclusivity, ensuring that governance is not monopolized by a single group or ideology.

- The Path Forward: Building a Democratic Syria

For Syria to successfully transition to democracy, the transitional administration must change its approach. Instead of relying on external approval and recognition, legitimacy must come from within—from the Syrian people themselves.

This requires:

- A commitment to democratic principles—pluralism, justice, participation, and human rights.

- A clear break from authoritarianism, ensuring that power is not concentrated in the hands of a new ruling elite.

- The inclusion of all political and social forces in shaping Syria’s new system of governance.

If the transitional authorities adopt an inclusive, transparent, and participatory approach, Syria’s democratic transition will succeed where others have failed. However, if power remains concentrated, and exclusionary policies continue, the country may face the same fate as Egypt and Tunisia—a slow and painful return to authoritarian rule.