Ankara is facing a new challenge in the Syrian war, which has manifested in a new dead end: Hay’at Tahrir al-Sham in Idleb. If confrontations occur between the group and regime forces, then the Syrian regime could carry out broad scale operations in Idleb. Damascus and Tehran are waiting for this eagerly. However, this sort of broad scale operation could create a new influx of refugees towards Turkey. If this influx occurs, then the ruling Justice and Development Party will be faced with another challenge, potentially losing some votes in March’s local elections. This could in turn lead to more political changes in Turkey.

There is no doubt that Ankara’s priority is to prevent pockets of the Kurdistan Workers’ Party (PKK), which is backed by the US in Syria. For Ankara, the People’s Protection Units (YPG)—the US ally in Syria—is just an extension of the PKK, which has waged war against Turkey for decades. Ankara believes that this pocket is nothing less than an existential threat.

Recently, Ankara has increased the tenor of its threats to militarily intervene on the eastern banks of the Euphrates River, where the YPG controls about a third of Syria’s energy resources.

If Ankara has not yet fulfilled its military promises, the reason for that is not just the American protection there. Carrying out this military action would also require Russia’s approval. However, for Moscow, the priority is without a doubt Idleb. President Vladimir Putin wants a final political settlement for Syria as soon as possible, and not a new military conflict that will delay this deal.

Despite that, the situation in Idleb is making the Russians impatient. Moscow, along with its ally Iran and the regime, wants full control over the area, to clear it of rebels, especially the groups they describe as having “radical mentalities”—and specifically Hay’at Tahrir al-Sham. However it also knows that if it launches a military operation in Idleb, the cost could be larger than it calculates. Civilian deaths and a projected influx of refugees could anger Europe. Victory is also not guaranteed.

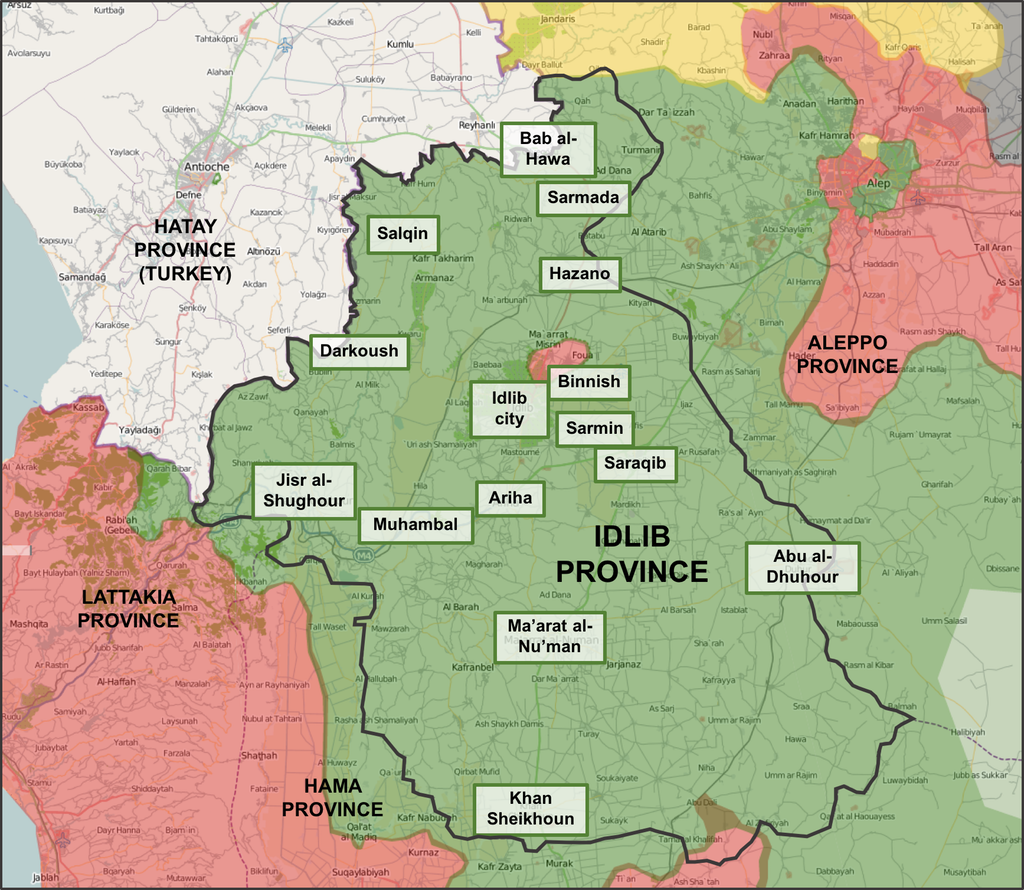

For this reason, Russia has decided to give Turkey a chance, which is the reason for the Sochi agreement that was signed between Putin and Erdogan. They agreed to set up a demilitarized zone that measures 15 to 20 km around the city of Idleb, and that radical groups, including Tahrir al-Sham, would withdraw from by Oct. 20 2018. However, since that date, the Russians have complained that the extremists are still in the demilitarized zone.

If Ankara’s first priority was to prevent the PKK-linked entity in Syria, the second priority is to establish and expand the pockets retained by the rebels in order to create a sort of stability in these areas, especially Idleb, and to make the rebels there into an entity with international legitimacy. In this sort of scenario, Tahrir al-Sham has no place, because it will win no legitimacy in the eyes of many because of its connection with al-Qaeda, despite its denials.

Tahrir al-Sham is trying to take control of some territory from other rebel groups in Idleb, and is trying to increase its grip over the M5 and M4 highway, which is the lifeline between Aleppo and Lattakia. However, the Sochi deal suggests that these two roads should be open to all until the end of the year, and the responsibility of that falls on Turkey’s shoulders.

So far, Ankara has tried to divide Hay’at Tahrir al-Sham rather than confront them directly. It achieved partial success, by backing competing groups. Can these tactics be implemented on the eastern bank of the Euphrates as well? Ankara may now need to consider this during the thorny time it’s gained in Idleb.

This article was translated and edited by The Syrian Observer. Responsibility for the information and views set out in this article lies entirely with the author.