She puts a collection of photographs in front of me, and speaks while looking and gently touching them as if she was trying to re-discover them. Wafa is a lady in her 60th year, her face is full of wrinkles and her eyes filled with tears. She takes my hands, mentally pulling me into her album of photos, one after another. My smile encourages her to speak in details. Maybe the place where the pictures were taken was Deir-ez-Zor, but Wafa’s presence is the only common tie between all of these photos.

“They weren’t of any importance when they were abandoned at my house on Cinema Fuad Street. But now the matter is different, they need special care. Look! They are going to be damaged,” said Wafa. She pointed to an old faded photo, putting it back in the album, closing it, and returning again to her tale.

“After the Free Syrian Army took control of the Jubeylah and Hamidiyeh regions of Deir-ez-Zor city, I left my house for Hassakeh almost two years ago, but I never lost hope in returning to it. Three of my children emigrated to Sweden, but I refused the idea because I won’t have my grave anywhere but Deir-ez-Zor. After he fled, my son was always telling me that, “We are Christians, and this country is no longer ours.” A day after the explosion at the Armenian Church, I realized that the country was not ours anymore. But nor is it a country for Muslims.

Simon puts his hand on his sister’s. He seems younger than her, but his grief is as great as hers. “Deir-ez-Zor was the last stop for those in the convoys of surviving Armenians who were forced to flee,” says Simon. “Our weary Armenian ancestors arrived in this land and the local tribes welcomed and protected them. We didn’t know any other homeland. We never felt that Muslims owned it any more more than we did.”

Will Deir-ez-Zor Be Barren of Churches After 2014?

Deir-ez-Zor is a city whose social structure did not allow any kind of discrimination between Muslims and Christians. The only difference was that Muslims headed in the direction of the mosques to pray, while Christians entered the churches. But 2014 was a different year in the history of the city. The bells of the church stopped ringing because the presence of Christianity was completely eliminated in the liberated areas of the city. And the most important and last Christian voice in the regime-controlled areas was silenced when the voice’s owner was arrested by regime intelligence services.

In the middle of 2014, the most important historical church in Deir-ez-Zor was blown up. Before the emergence of the hardline Islamic groups, all activists in Deir-ez-Zor agree that Christian practices were affected just as much as Islam. Khaled, a member of the Hijra Illa Allah (“Immigrants to God”) Brigade, explains this. His intermittent voice via Skype recalls memories of how he first entered the church, accompanied by comrades from the Syrian Free Army, in order to clean it. He couldn’t prevent his sense of heartache from reaching me, “That day I felt I was performing my religious and social duty toward my Christian neighbors. The activists showed great interest in protecting the Christians’ properties from the people of the city—they considered and protected them as if they were their own possessions. This was chivalry toward a stranger who had no support or tribal protection. In this way, the churches remained safe and nobody thought to threaten them. Churches were protected by the inhabitants of the city.”

Khaled explained this before his connection was cut off and his voice went quiet. But voices like Khaled’s from that segment of the population began to dwindle after the Nusra Front took control of the city. For the first time, you heard people talk about Christians being infidels, and saying their money and blood were halal. This was not announced in public, but according to Saleh, one of activists of Deir-ez-Zor, it was clearly obvious from the behavior toward [Christian] properties. Saleh added that ISIS’ entry into the city accelerated the pace of this change. People openly described Christians as infidels, saying that the country must be cleared of them. But ISIS didn’t find any Christians in the free areas to expel or label as infidels. The last Christian, who had remained in the city throughout the war, left the city before ISIS’ entry. ISIS found only churches that, by will of destiny, were located in the areas they controlled.

Where Church Bells are Sold as Scrap—You are in the Kingdom of ISIS

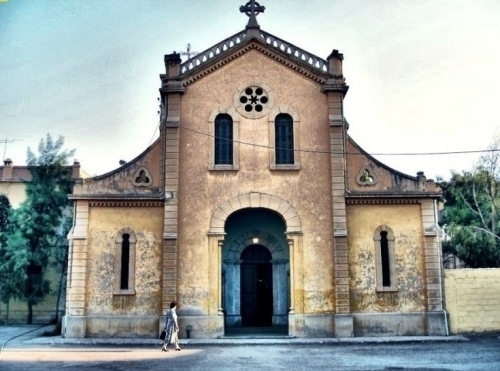

On September 21, 2014, a huge explosion woke the residents of Al-Rasheediyeh neighborhood. In wartime, such explosions are not exceptional events, but this was. The church’s neighbors left it safe the night before the explosion, but in the morning they found nothing left of it except the tower with the cross on it. Because of its religious symbolism, the church is considered a place of pilgrimage for the Armenian diaspora. According to Saleh, in May 1985 the foundation stone of the church was laid at the presence of Holiness Catholicos Karekin I.

The church has a main entrance with a façade decorated with carved crosses. On the side of the altar there is a wall decorated with Armenian and Arabic inscriptions, with two fountains on the top that stopped flowing after the explosion. On the left side of the altar there is a memorial wall holding a stone cross with miniature votives. The wall tells the tragedy of the Armenian people. Against the main entrance there is a huge monument commemorating martyrs, and a cross-stone, or khachkar, brought from Armenia, lit up with a flame of immortality burning permanently in front of it. On both sides stand five Armenian martyrs from around the world. The church was established on the left side of the square, and at the bottom a column runs through the center of the church. The column is called the emission column, and in its base the remains of the martyrs’ bones were buried. The hall also contains—rather, had contained—displays for books, publications, and documentary photographs showing the suffering of the Armenian people during the massacres, as well as a map showing the places of the genocide, and a full survey of the paths the exiled Armenian people followed—roads which many Armenians will walk heading north.

The destruction of the church was terrifying, according to Saleh, but the most horrible thing was the scorn with which people treated the small but important things—the church had been stripped of its sanctity, and its bells were now considered just metal to be sold in the street as scrap.

Jack al-Abdullah

On a thin rope connecting two great walls, swings the cartoonist of all revolutionary symbolism. He refuses to look at you, ignoring you. And Jack al-Abdallah insists on ignoring you when you look at him, trying to convince him to come down and replace the pictures he has put on display with other ones, or to clean up the newspapers and magazines he scattered on the pavement in front of his library, “Al-Kawakibi,” which was closed by the Syrian intelligence services. So as he was cleaning up the pavement in front of his library, a detective, the shoe seller on “Basta,” informed the intelligence services about everything he saw and heard in the street.

Abou Abdullah was known as an anti-regime activist before and during the Syrian uprising, and because of this many young people gathered around him. After the revolution became militarized, he was forced to leave his house on Hammoud square, as did thousands of Deir-ez-Zor inhabitants, but he refused to leave the city. Abou Abdullah moved to Al-Jura neighborhood, known for its massive population density, and he continued providing services to the city and its population until he was arrested by the intelligence services in October of this year.

In the area controlled by the regime, there weren’t any churches to pretend to protect because the Christian community didn’t live in these places. But now Abdullaah is there, and after his arrest he disappeared behind bars—the last Christian voice in Deir-ez-Zor. Meanwhile, ISIS works in the free areas to erase any color other than the black [of its flag], which it celebrates.