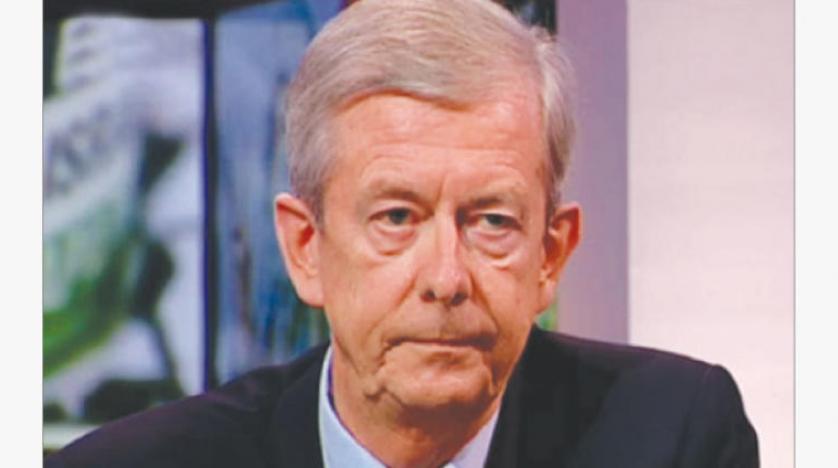

Nikolaos van Dam is a Dutch diplomat, scholar and the author of a classic text on Syrian politics and sectarianism: The Struggle for Power in Syria (2011). During the Syrian uprising, he served as the Dutch Special Envoy to Syria, operating from Istanbul, and had intensive contact with most of the parties involved in the conflict.

I met Dr. Nikolaos van Dam in Damascus years before the revolution. His deep knowledge and mild nature fascinated me. In 2016 I saw him again in Istanbul. He was the Special Envoy for Syria and he had only become more elegant and knowledgeable. Not many people can be both academic and active, but Van Dam is. Retired now, Van Dam has more time to contemplate Syria and to see where things went wrong in the Syrian revolution. His latest book Destroying a Nation: The Civil War in Syria (also in Arabic (2018): تدمير وطن: الحرب الاهلية في سوريا) is maybe the most comprehensive and objective report on Syria. He explains the recent history of Syria, covering the growing disenchantment with the Assad regime, the chaos of civil war and the fractures which led to the rise and expansion of the Islamic State. Through an in-depth examination of the role of sectarian, regional and tribal loyalties in Syria, Van Dam traces political developments within the Assad regime and the military and civilian power elite from the Arab Spring to the present day.

Below are exerts from The Syrian Observers’ interview with Dr. van Dam. The full interview will be published in two parts on Tuesday and Wednesday.

- Whereas direct dialogue with the regime was rejected relatively early on in the conflict when there were several thousands of dead as a result of the war, the regime, cynically speaking, gradually is becoming more accepted as a matter of reality after more than 500,000 dead.

- The question should also be taken into account of whether only the party that “pulled the trigger” was responsible, or also the party that provided the other party with the motivation to attack it, knowing very well how the dictatorship was going to react (if past massacres, like Hama in 1982 were something to go by).

- The longer the war has taken, the fewer are the possibilities for any peaceful compromise between the regime and the opposition groups, assuming that there ever has been any room for political compromises.

- What might perhaps have been acceptable for the regime several years ago, when circumstances were quite different, is not necessarily acceptable now. Possible chances have been missed by refusing any real dialogue with the regime in the past (which applies also to many Western and Arab countries), and by maintaining the demand that the regime had to disappear and brought before justice (however much such a demand may have been justified on grounds of justice and morality).

- I am aware, of course, that many opposition Syrians will fully disapprove of what I am saying here, but under the present circumstances I see no clear way how they could fully achieve their stated aims. The alternative is, perhaps, to wait for a more successful revolution, from their perspective, whenever; but in the meantime, life inside Syria has to go on.

- The opposition (or I should say the many opposition groups) should have considered the extremely violent and bloody consequences and prospects. With hindsight one might argue that the opposition groups should have thought at least twice, or more, before starting the revolution, both peaceful and armed. But this is easier said (now, afterwards) than that it could be done.

- If you want to defeat and kill a lion—Assad means lion in Arabic—you must be well-prepared beforehand to be the stronger and better armed party, so as to prevent being defeated and killed oneself.”

- The visit of US Ambassador Ford and his French colleague Chevallier in July 2011 to the demonstrators in Hama was interpreted as a positive signal that US and French support was forthcoming. But in the end, it did not come as expected or imagined.

- The opposition groups and demonstrators should have known that, rationally speaking. But they were emotionally overwhelmed by the imaginary prospects of success.

- The bloody conflict was unavoidable, both by violent means, as well as through peaceful efforts that turned out to be not that peaceful after all, taking the professed aims into consideration: “toppling the regime” and “executing the president”.

The interview was conducted by Wael Sawah.

This article does not necessarily reflect the opinion of The Syrian Observer.