Sadiq Al-Azm′s productive life can be split into three stages: the sixties and seventies in Beirut, the eighties and nineties in Damascus, and the early years of the 21st century, when he divided his time between Damascus and the rest of the world.

Similarly, the personality of this Damascene intellectual may be said to have three distinct facets: the academic scholar, the political activist, and of course, the person of Sadiq al-Azm.

On the academic front, Sadiq Jalal al-Azm lectured in numerous universities, including the American University of Beirut, the Damascus University and the University of Jordan for a brief period in the late sixties, as well as in several Western universities.

His renowned books reflect the ideas of a thinking protagonist engaged in public affairs rather than an academic closeted away in an ivory tower.

Affinity with criticism

His book, ″In Defense of Materialism and History″ (1990), provides the most insight into his own philosophical views, simultaneously expressing a clear political agenda at a time when communism was collapsing. In this work, al-Azm demonstrates an established foundation of materialistic and historical neo-critical theories and reveals the progressive, democratic partiality of his thoughts – just when the time was ripe for such thoughts to see the light.

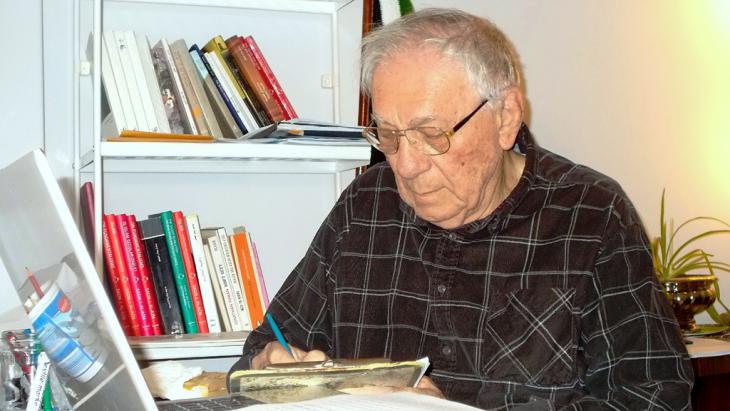

Considered one of leading Arab intellectuals writing today, Sadiq al-Azm has been an advocate of freedom of speech, human rights and democracy for decades. He is synonymous with promoting dialogue between the Islamic world and Western Europe. Owing to the escalating violence in Syria, the philosopher and his wife were awarded political asylum in Germany in 2012

Al-Azm′s interest in public affairs was directly triggered by the Six-Day War in 1967, although its ideological emphasis would change with the passing of the decades. Initially, during the 1960s and 1970s, he favoured leftist, pro-Palestine and pan-Arab ideologies. The 1980s and 1990s saw him turn increasingly to rationalism and secularism, before he finally settled on liberal democracy with the onset of the 21st century.

Sadiq′s interest in politics has been most pronounced during the first and third stages of his life. During the rise and fall of the pan-Arab movement, he was outspoken in his support for pan-Arabism; in recent years, by contrast, he has returned to his roots in support of the Syrian population. He was actively engaged in the ″Damascus Spring″ forums and the work of the ″Civil Society Committees″ at a time when Syrian intellectuals were petitioning for democratic reform.

A leading voice

As for the second stage of his life, i.e. the last two decades of the 21st century, Sadiq′s involvement erred more on the intellectual. At that time, the Arab world was submerged in tyranny on the one hand, and Marxism, the backbone of Sadiq′s intellectual identity, was losing ground due to the collapse of communism, on the other. During this period, many academics found it expedient to put their political convictions on the back burner.

Sadiq al-Azm′s most famous publication which still enjoys widespread appeal today is ″The Critique of Religious Thought″ (1969). It was this particular book that caused the author to be sued for denigrating Islam in Beirut, when he was professor emeritus at the American University there.

In general, it is safe to say that Sadiq Jalal al-Azm has made an impact over the last fifty years as an intellectual who is prepared to speak out about public affairs.

During this entire period, his utterances have been characterised by lucid style and a clarity of expression which has set him apart from his peers and contemporaries.

He is also known for constantly raising controversial issues, especially in his books ″Self-Criticism after the Defeat″ (1968), ″The Critique of Religious Thought″, ″The Mentality of Proscription″, and ″Beyond the Mentality of Proscription″ (1990s). These days, he is highly vocal in the debate about Syria; many of his interventions are considered controversial, the reaction is often one of ridicule and allegation.

Thought is always debatable

One of Sadiq′s frequent claims is that every act of thought is debatable. This is no doubt an opinion with which many would disagree, but it must be said that he has always articulated his standpoints, critical, controversial or otherwise, with enviable clarity.

Sadiq was born into an aristocratic Damascene family, which likely fostered his early secularism. From the nineteen thirties onwards (and still earlier in Istanbul), secularism was actually quite common among aristocratic Muslim families living in Damascus and Aleppo.

Goethe Medal prize-winners 2015: Neil MacGregor (left, 68), British museum director and founding director-designate of the Berlin Palace, the Syrian philosopher Sadiq al-Azm (right) and for the German-Brazilian culture manager Eva Sopher, whose daughter Renata Rubim (2nd from left) and god-daughter Ulrike Mcchlegel (2nd from right) pose for photos after the awards ceremony on 28.08.2015 in Weimar (Thuringia)

Indeed, Sadiq combined this elitist secularism with his leftist, social and political ideas. The resulting configuration led to him regarding himself not just as a Syrian, but as a cosmopolitan citizen, who could feel a ″spontaneous, justified and natural belonging″ to any country, city and culture. Compared to other Syrian intellectuals who have relocated to the West, and particularly during the third stage of his career and life, Sadiq has proved the most effective in adopting an outward, global perspective while remaining actively involved in his country′s affairs and the debate surrounding it.

It may be argued that the certain distance one senses between Sadiq and those in his immediate environment are down to Sadiq′s upbringing, his intellectual education and his own personality. Indeed, it has never been easy to get to know him.

No followers and no personality cult

Furthermore, he himself says he prefers colleagues, opponents, counterparts, critics and friends to partisans, adherers, followers, imitators and admirers. It is therefore hard to claim that a ″Sadiqi″ movement or a ″Sadiqi″ school of thought exists.

Indeed, in the long run, the lack of a movement is probably wiser and more democratic than rallying support, which has become synonymous with fanaticism and totalitarianism. Only time will tell.

Sadiq Jalal al-Azm has been awarded the Goethe Medal at a time when the Syrian revolution has turned overwhelmingly apocalyptic. There is no question: the recognition of the individual was deserved, but the award is a broader act of recognition of Syria the country.

One timeless attribute of Sadiq and his work is this interdependence between the personal and the public: a non-conformist intellectual firmly focused on the values of freedom, justice, reason and globalism.

Responsibility for the information and views set out in this article lies entirely with the author.