Kheder Khaddour, a Syrian scholar, tells The Syrian Observer that the Syrian army should not only be evaluated for its fighting capabilities, which are arguably very weak. Rather, decades of corruption within its ranks have created networks of patronage that have provided a very efficient alternative chain of command, which has helped the regime adapt quickly to the changing dynamics, in particular through the creation of paramilitary groups.

You argue in a recent paper that the weakness of the Syrian army is also a factor of strength. Can you explain this contradiction?

When the uprising and then armed conflict broke out in 2011, the Syrian army was hardly combat ready, having been crippled by decades of corruption through various networks of patronage and nepotism.

However, the paradox is that these same networks that had weakened the army’s ability to fight, morphed, post-2011, into a parallel chain of command that was much more efficient and responsive than the official army structures. This helped strengthen the regime’s grip over the officer corps and facilitate the creation of paramilitary forces, in turn allowing the regime to adapt quickly to the changing dynamics of the conflict and entrench itself in territories critical to its survival.

If evaluated for its conventional fighting ability, the Syrian Army is weak, but in the current conflict it remains relevant and central to the regime’s survival through its investment in various functions other than direct combat.

For instance, the Syrian army has remained the central platform for coordinating and providing logistical support to the various pro-regime forces deployed around the country, for instance by sourcing and distributing weapons to the paramilitary groups. Symbolically, the army also continues to play a major role in legitimising the regime’s leadership of the country.

From 1970, when Hafez al-Assad took power through a military coup, until now, almost all regime security personnel in the two most powerful security agencies, Military Intelligence and Air Force Intelligence, have graduated from military colleges and academies, including Bashar al-Assad. This institutional skeleton remains standing today, with the military colleges continuing to graduate officers and provide the regime with trained security personnel.

The army is also the second largest landowner in the country after the Ministry of Local Administration; it runs the military construction company, the largest construction company in Syria, and the military housing establishment, which is the largest developer and allows the army to continue providing officers with housing, allowances and other benefits. In fact, the Aleppo governorate has already contracted the Institution for the Implementation of Military Construction, a company affiliated to the army, to clear the destroyed streets in recently recaptured Eastern Aleppo, which is likely a first step for further reconstruction contracts.

Why then, despite all these strengths you are referring to, have we seen such a rise of the militias and a relatively weak participation of the army in the battles?

Given that the army entered the Syrian conflict effectively unfit for combat, if the army had tried to sustain large scale street fighting it would have almost surely fragmented and collapsed. In late 2011 into 2012, the regime and its allies realised they were entering in a prolonged conflict that required a long-term strategy. A central part of this was to delegate frontline fighting to smaller, agile groups — such as the militias — and to keep the Syrian Army itself behind the frontlines running logistics and, for example, providing artillery support.

There are many who would argue that the army has disappeared and the only ones fighting for the regime now are the militias; I would counter that the leadership in the officer corps created the militias in order to keep the army structurally intact.

The Military Service Law, which is the framework text that governs all issues pertaining to the army, actually allows for the creation of militias, noting that the Syrian military is comprised of four different parts: ground forces, the navy, the air force, as well as “any other forces that are required by the circumstances.” In other words, the militias are not outside the fold of the army.

Rather than relying on militias, why didn’t the army establish new military units of its own?

You have several issues here. The first has to do with the army having lost its capacity to mobilise and recruit. Even before 2011 it had not been perceived as an efficient and professional institution. Rather, the army was widely known to be a crumbling structure riddled with corruption whose primary function was to prop up a declining officer class. It had long ago lost any venere as a defender of the country and those who went into the army voluntarily usually did so because they saw themselves as having no other viable option for a livelihood.

It was common for young Syrians to seek any means available to avoid the mandatory military service, including university exemptions, bribery, or even leaving the country entirely. When armed conflict broke out in 2011 and the Syrian Army responded by extending the term of mandatory military service indefinitely, its difficulty in recruiting became acute. Within the officer corps, recruitment had been slightly better before 2011. Even though the officer corps was majority Alawite, the army could still attract recruits from across the country. As the conflict polarised society along sectarian lines and local identities, and the army became a blatant tool for regime survival, new recruits to the officer colleges became almost exclusively Alawite, with small numbers of other minorities.

On the other hand, finding militia recruits has been much easier: they tend to come through informal community networks and family ties; joining a militia has usually meant a fighter can stay close to home, creating a sense of personal buy-in as the fighter feels he is defending his local community; militias pay better than the Syrian army and are also more flexible regarding joining and leaving.

The benefit of militias and paramilitary groups is that they are also much more agile fighting forces than a national army. With local commanders they can respond and take action swiftly, unencumbered by the bureaucratic machinery and centralised decision-making characteristic of an army – a key asset in the context of the irregular warfare characteristic of the Syria conflict.

The Syrian army’s decision to resort to lighter, locally recruited paramilitary groups may also have been inspired by its experience during the Lebanese civil war. In the 1980s, during its deployment there, the Syrian army became exhausted by the civil war and eventually opted to rely on local militias for frontline fighting, while maintaining strict control over their logistics support and organisational arrangements.

Could we then say that the militias are somehow part of the army and of a clear military hierarchy?

To respond to this question, one needs to point out that the Syrian army has ever-mutating internal mechanisms of functioning. In Syria, as elsewhere in the Middle East, the line between the formal, regular security forces and the informal, irregular forces is increasingly porous.

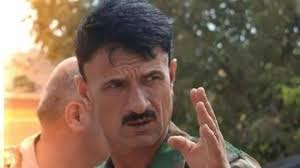

The case of the Tiger Forces, led by “The Tiger” Suheil Al-Hassan, is a good example. As with almost all officers serving with the security services, Hassan had been an army officer before being mandated by the Syrian Defence Ministry to serve in the Air Force Intelligence. When the uprising started, he was sent to lead an operations room in Daraa, where he contributed to the repression of demonstrators.

As protests began forcefully challenging the regime, Hassan took to wearing his army uniform again, despite intelligence officers rarely wearing official uniforms. The effect was to re-establish his army credentials which, combined with his personal charisma and family and community connections, he used to attract recruits and form a paramilitary corps, the Tiger Forces. The 4th Division of the Syrian army then sent one of its brigade to fight with the Tiger Forces. Hassan funded his militia through long-standing connections with the regime personalities. Specifically, Rami Makhouf, the billionaire Syrian businessman and Bashar al-Assad’s cousin, funded the Tiger Forces through his charity, “Al-Bustan.”

In short, Hassan is at the same time an army officer, an intelligence officer and a militia commander, who can variously associate himself with the institutional legitimacy of the army, the regime’s informal networks, or his Alawite sect and local identity, depending on what is pragmatic for the circumstance. Similarly, it is difficult to define whether the Tiger Forces is a militia or an army brigade. Its members are locally recruited, it is headed by an intelligence officer, it receives logistics support from the Syrian army and is financed privately by prominent regime figure.

Incidentally, Hassan was promoted in January 2017 to the head of Air Force Intelligence in Aleppo.

The second part of the interview is online here.

Kheder Khaddour is a non-resident scholar at the Carnegie Middle East Center in Beirut. His research focuses on issues of identity and society in Syria

Mr. Khaddour was interviewed by Jihad Yazigi.