“During the presidential elections in June 2014, they brought us a box to vote for Bashar al-Assad! How could we vote for him while we were political prisoners? It was the worst day we had. We were forced to vote, and we were crying after his election. After three daughters refused to vote for him, we heard the voice of an officer saying: They brought them down to the cells, and they were forbidden to eat and drink … They were beaten and then forced to vote for Bashar.“ This is how Lula Agha recalls her time in prison. Her words summarize the Assad regime’s concept of the electoral process and its relationship with voters.

Lula Agha’s story, titled: “Meeting in the Slaughterhouse” that featured in the book “So As Not to Be on the Margins,” by Syrian researcher Lama Qunoot, is heart-rending story because of the violence and humiliation this woman received, without help even from her family and relatives. Lula, born in 1984, is a housewife who did not finish her schooling. She lived with her husband and her four children in Salah al-Din area, where the first Syrian demonstrations erupted and became the first area liberated from the regime in Aleppo.

Her family and husband were silent and neutral. Her husband’s family were shabiha, filing security reports and taking part in the looting, whether or not the property belonged to the peaceful opposition that wanted the fall of the regime. She participated in weekly meetings about the revolution and went out on three demonstrations, before her husband stopped her and she moved away from politics. She and her family were forced to move from one area to another because of the shelling. Her husband’s brother Mohamed informed on her because she refused to register her youngest daughter in his name, since he and his wife could not have children. On Oct. 20, 2013, Air Force Intelligence officers stormed her house and arrested her, and the next day, Political Security arrested her husband from his workplace in the railway department.

Lula did not stay long in detention. But she was tortured extensively, despite being pregnant. After she got out, she started working in a sewing workshop to support her children. She contacted a person who could get her husband out of prison for 50,000 Syrian pounds, and said: “I didn’t have even a pound, and so I told my mother-in-law, and she sent her son Mohamed with me to meet the person … When the person working in the branch learned that my husband’s family would not pay, he called me, and asked me meet him alone to discuss the issue. I understood what he wanted, so I turned my phone off permanently … Two weeks later I was arrested for a second time … They took me to the Military Security on Feb. 17, 2014… Again, they started torturing me. ”

Lula was moved between the Military Security branches in Hama and Homs, and spent three months in the “Palestine Branch” in Damascus. She was released from Adra prison on Dec. 10, 2014. But on the day of her release, a message arrived at the prison to transfer her to Political Security. There, she met her husband in the investigations room. Under torture, he had made baseless confessions about her and his roles in arming the revolution. She denied his statements, and he retracted his confessions, and so they started beating and harassing her. She said: “They stripped me, and one of them raped me in front of him while two of them held me down. My husband could not bear what he saw, and he fell, no words escaping. I thought he was unconscious—it never occurred to me that he had died. They took him outside the room, and I got dressed and they brought me back to the cell.” The next day, she was called back for sessions of torture and electric shocks.

In February 2015, Lula was transferred to Adra prison, and then released on Dec. 16, 2016. But she remained on trial, and in the third hearing, the judge sentenced her to 16 years imprisonment. She had a month to submit to the ruling or appeal, and so she decided to go to Idleb, and then she settled in Turkey with her children—with the exception of her young daughter, whose uncle, Mohamed, had managed to keep.

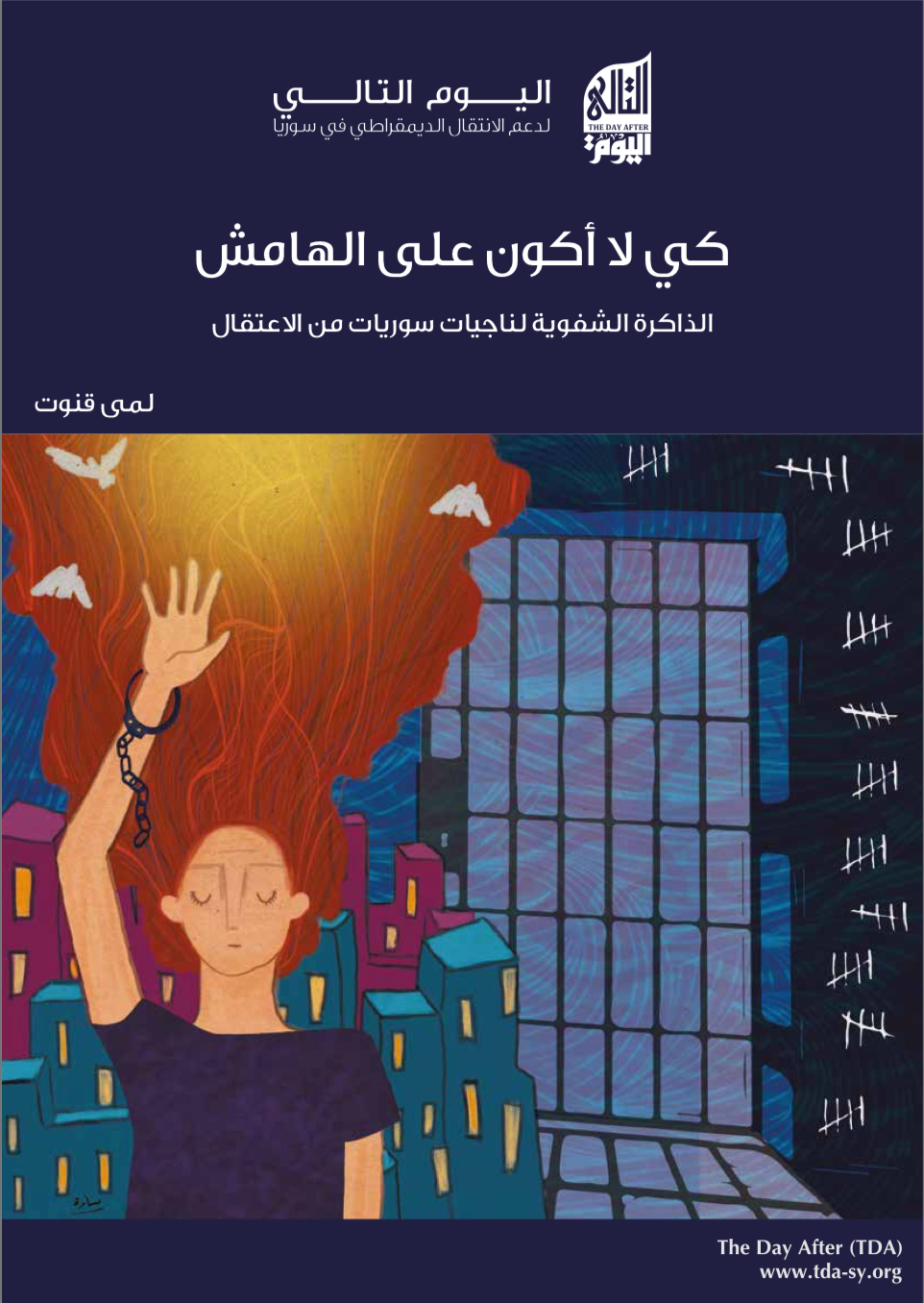

The book, “So as Not to Be on the Margins: An Oral History of Syrian Female Survivors of Arrest,” was published by The Day After organization at the end of 2019 and includes stories of 11 former prisoners in Syrian regime prisons after the outbreak of the Syrian revolution. The reader can notice the efforts Lama Qunoot made in preparing the characters, managing the dialogues, and from there formulating them in a graceful manner in separate stories, each with a separate title and a unique heroine—despite the pain that radiates from within.

The book’s chapters are separated by abstract paintings from Syrian artists. The heroines are of different ages and backgrounds, differing in terms of education and life experience. They come from many regions, including Damascus and its countryside, Aleppo, Hama and Deir ez-Zor. The questions asked of them were not limited to the conditions of detention and methods of investigation and torture; rather, they covered all stages of their lives, in Syria and in countries of asylum. Lula Agha, Amira Fouad al-Tayyar, and Mona Baraka were the only ones who gave their real names. Three women just used their first names: Hanadi, Zainab, and Reem. Others spoke with pseudonyms: Narjis, Norhan, Noor Ward, and Yasmin al-Shami.

This article was translated and edited by The Syrian Observer. The Syrian Observer has not verified the content of this story. Responsibility for the information and views set out in this article lies entirely with the author.