One of the characteristics of regimes that impose violence, and which remain under emergency and exception, is a feverish search for a certain legitimacy. Parliamentary regimes say they draw their legitimacy from “the will of the people”. Religious regimes say they represent God’s will, from which they derive their legitimacy.

On the other hand, military and security systems, often nationalist, attribute their legitimacy to the nation’s determination and interests, which are complemented by the “battles of destiny” and their bloody price.

The Algerian regime, for example, emerged from the Algerian revolution described as the “Revolution of the Million Martyrs”. This legitimacy sustains five regimes and justifies staying in power for more than five decades.

Jamal Abdel Nasser overthrew the family of Mohammed Ali – the “corrupt”, the “unfaithful” and of Albanian origins, and then signed with the British the treaty of evacuation, before nationalizing the Suez Canal and fighting the 1956 war against Britain, France, and Israel.

Even Saddam Hussein, after magnifying the importance of the 1968 revolution, in which he was a key player, assumed his presidency in parallel with the first Gulf war, which was described as a war to defend the eastern front of the Arab nation. The rulers of what was known as South Yemen turned the war of independence from Britain into the basis of their power for a third of a bloody century. Muammar Gaddafi, until his last days, remained the symbol of Al-Fateh September Revolution.

In this category of regimes, we find a paradoxical situation: Hafez al-Assad. There is no doubt that the allegations regarding his colleagues mentioned above involved a remarkable amount of falsification of history, as well as a similar amount of pain, but a degree of truth was established. Assad, on the other hand, remained for a long time away from such allegations, but he has caused more pain than all of the others.

Even the Baathists, who consider their party coups in Syria to have opened a horizon of history, have found nothing to say about late Assad: He did not have a vital role in his party’s 1963 coup. He was the third of three members in the Military Commission, succeeding Muhammad Omran and Salah Jadid. The key roles in the coup were in fact assumed by non-Baathist officers, most notably Ziad Hariri, before the Baathists stole their already stolen power.

In the 1966 coup, Assad’s ambition did not surpass that of assuming the Ministry of Defense replacing the wretched officer, Hamad Obaid. It is true that his coup in 1970 gave him for the first time some legitimacy within the context of a “corrective movement” for a garbled path; but as the coup was named “Assad’s September” in Jordan, he lost both the nationalist and revolutionary auras.

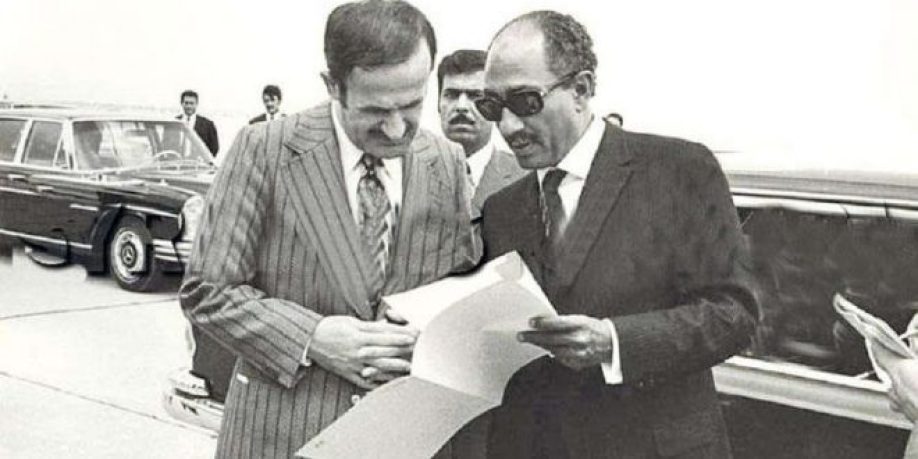

This is what changed in the October 1973 war. Assad became the “hero of October”. By claiming that this fabricated war was a historic victory, his stature grew to an unprecedented level. He wiped out the 1967 insult that came with his appointment as Minister of Defense. He became a “regional player” in that vulgar media expression. The separation between him and Anwar Sadat soon reinforced the image wanted to be drawn for him.

There, in Cairo, betrayal and duplicity; here, in Damascus, steadfastness and confrontation. October is ultimately about Israel. Victory over it entails an enormous ability to believe the unbelievable.

In any case, there were those who believed the October novel and those who did not, but acted “as if” they did, according to the equation described by the American researcher Lisa Wedeen about Assad’s Syria.

But on the basis of October legitimacy, the nascent leader was able to do what was not done. The entire Mashreq region, especially Lebanon, has become a theater for interference. Preventing the Palestinians from Palestine’s representation has gone so far.

The tragedy of Hama and the conquest of the rest of Syria became a daily routine. He could be defeated in 1982 and then declare that he was preparing for a victory of a place and time of his own choice.

Assad’s experience demonstrated the delusory influence of the conflict with Israel. It even magnified the myth.

Thus, the legitimacy of the October War has become the most important foundational material of the Assad regime.

It compensated for every shortage and every lack. Because of the enormous lack of legitimacy based on actions, the importance of the October legitimacy has grown. It seemed urgently needed to complete the act of blind violence against Syrian society and its surroundings.

With a combination of this violence and this inflated legitimacy, Assad the father managed to remain in his absolute presidency until his departure in 2000; he was also able to offer the rule to his son.

Thus, Hafez al-Assad “did not sign” because the signature meant no less than an earthquake that affected his sole legitimacy. Playing in Palestine has become the cause of existence and the cause of sustainability.

A television station and presidential adviser recently boasted of the late Syrian president as “the man who did not sign.” Indeed, if he had signed, the station would not have existed and the adviser never consulted. I wish he signed.

The Syrian Observer has not verified the content of this story. Responsibility for the information and views set out in this article lies entirely with the author.